Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

Washington's newly minted tariff ceasefire reads like an armistice drafted mid-game rather than the whistle that ends play. The numbers make the point more sharply than any diplomatic communiqué: after six years of tit-for-tat duties, the United States enters this 90-day window nursing a deeper economic bruise than the rival it sought to pressure. Beijing arrives with healthier external accounts, spare monetary ammunition, and a more straightforward industrial strategy. At the same time, the US confronts higher prices, a wider trade gap, and voters who mistake those problems for signs of strength. This asymmetry frames the fundamental thesis of the truce: it reveals structural weaknesses, such as the reliance on imports and the lack of a comprehensive industrial strategy, that the United States must fix or watch hard-won technological advantages erode behind the comforting illusion that it is still calling the shots.

Counting the Cost: Tariffs as a Regressive Consumption Tax

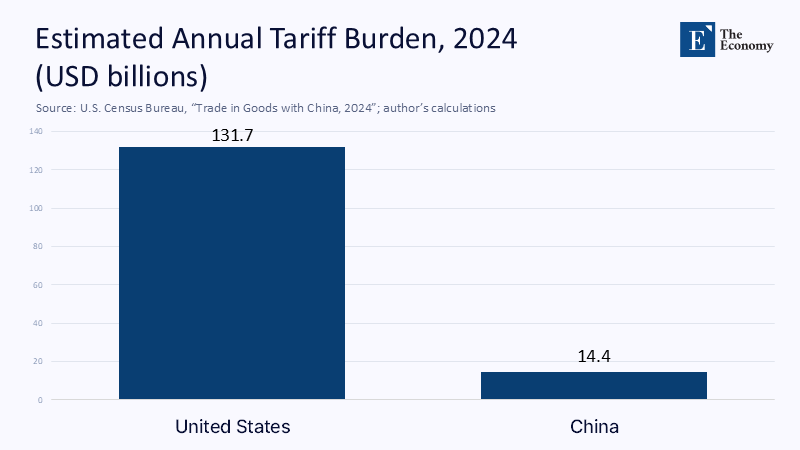

Tariffs rarely behave like sniper fire; they scatter metal through the domestic economy in ways that hit consumers first and hardest. US households bought roughly US $439 billion in Chinese goods in 2024 and faced an average headline duty just under 30% once Section 301 and the latest "reciprocal" surcharges are folded in. China's retaliatory duties on American goods, by contrast, hover near 10% and cover a markedly smaller base of US $143.5 billion in US exports.¹ Multiply the two pairs of numbers, and the United States shoulders an annual pass-through of about US $131.7 billion, six times Beijing's estimated US $14.4 billion bite. Even after substitution effects, that transfer equals 0.48% of US GDP, a direct subtraction from household purchasing power that no one voted for, but everyone pays at the register.

These figures expose an arithmetic imbalance and a deep design flaw: the United States is trying to fund an industrial policy through a regressive consumption tax. Because low—and middle-income households devote a higher share of budgets to imported consumer staples, the policy magnifies inequality even before macro effects—like delayed equipment upgrades or slower real-wage growth—kick in. This underscores the crucial need for targeted policies that consider the impact on different income groups and industries. Beijing, meanwhile, spreads a much lighter levy across a far larger population and couples it with targeted VAT rebates to shield strategic exporters.

The Hidden Inflation Trigger: How Duties Distort the Price Pass-Through Cycle

Official inflation looks calmer than the grocery cart feels. April's headline CPI clocked in at 0.2%, yet core goods prices are still running 5.1% above a year earlier. The mismatch is classic tariff lag: inventories ordered pre-duty hide upstream cost shocks for roughly two quarters. Once those warehouses clear, importers either surrender margin or raise sticker prices. Surveys from the National Retail Federation indicate that 63% of large buyers plan to lift shelf prices before the holidays, the largest pre-Christmas share in two decades. The Federal Reserve's conundrum is cruelly simple: clamp down on demand with higher rates and risk manufacturing layoffs, or watch tariff-fed inflation rekindle precisely when it hoped to declare victory.

Beijing's Macro Arsenal: Deflation as a Strategic Buffer

China's current economic challenge is a different one—deflationary slack. With producer prices sliding 2.7% year-on-year, the People's Bank of China can increase liquidity without sparking inflation. This deflationary cushion allows industries from electric vehicles to photovoltaic panels to slash export prices, undercutting US manufacturers who lack similar credit subsidies or depressed input costs. The 6.1% rise in industrial output in April signals that Beijing's chosen sacrifice is margin compression, not volume loss. If the goal is long-term market share, accepting thin margins during a price war is a textbook strategy.

Supply-Chain Divergence: Where Multinationals Are Moving

Politically potent stories about an exodus from China obscure the data: only 7% of the foreign factories that left the mainland between 2020 and 2024 landed on US soil. The larger share settled in Vietnam, Mexico, and Indonesia, which preserve low-cost supply chains yet keep final assembly within easy reach of US consumers. US Customs records show that goods labeled "Made in Vietnam" but containing Chinese intermediate content rose 22% last year, evidence that tariff walls often re-route trade flows instead of reshoring them. The trade deficit, far from shrinking, widened as American firms re-imported finished products layered with mark-ups from new transit nodes.

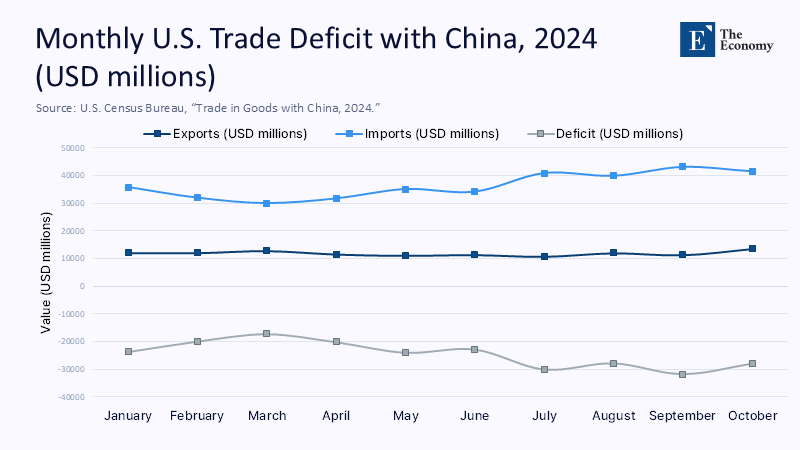

Figure 2 visualizes how the deficit deepened through the year's second half, even as new tariffs took effect—a counterintuitive but predictable outcome once firms front-load imports ahead of higher duties and then search neighboring economies for workarounds. The line is a warning light display: each spike confirms that tariffs alone cannot solve imbalances rooted in domestic savings shortfalls and capital inflows that prop up the dollar.

The Fiscal Feedback Loop: Debt, Dollar, and the Structural Trade Gap

Tariff revenue—roughly US $60 billion a year—covers less than one month of net interest on the federal debt. Worse, the duties themselves encourage a stronger dollar as importers scramble for greenbacks, which widens the deficit they are supposed to shrink. The dynamic is visible in Treasury International Capital flows, where foreign official purchasers have trimmed holdings of long-dated Treasurys for four consecutive quarters even as private appetite for short bills rises. China cut its stock by another US $32 billion last year, putting downward pressure on long-end prices just as the Congressional Budget Office forecasts interest outlays breaching 3.3 % of GDP by 2028. In short, America is partly taxing goods to finance the higher interest costs that the tax helps generate.

Krugman, Keynes, and the Populist Lens: Competing Narratives in Policy Debate

Paul Krugman's insistence that "the trade war isn't over" deserves an addendum: it may never end if its political returns outstrip its economic costs. Protectionism plays well in countries ravaged by automation and opioid deaths because it offers a villain with a foreign passport. Keynes might have diagnosed this as a classic case of "animal spirits" crowding out statistical reality; today's economists see it in polling that rates tariffs more favorably among voters who suffered the least from off-shoring. That perception gap helps explain why Washington reaches again for blunt duties rather than painstaking, sector-specific incentives that poll poorly because they are hard to explain in a television sound-bite.

Education as Economic Security: Curriculum Depth vs. Protectionist Slogans

For an education-policy readership, the trade war underscores the cost of leaving economic literacy to pundits. Surveys by the National Council on Economic Education show that fewer than 23% of high-school seniors can correctly define a tariff's incidence. Those seniors become voters who see every bilateral deficit as a scoreboard to be levelled by taxes, not productivity. Embedding real-time case studies—like the scattershot impact of 2025 duties—into macroeconomics curricula would do more for national competitiveness than any hike in steel tariffs. Classroom simulations that force students to adjust supply chains or raise prices after a duty shock reveal, in one semester, the futility of winning a modern trade war by taxing intermediate inputs.

Policy Roadmap: Targeted Discipline Over Blanket Tariffs

A smarter American playbook would replace broad tariffs with carbon-adjusted border fees, outbound-investment screens for quantum and AI, and conditional subsidies pegged to domestic value-added thresholds. Redirecting tariff revenue into a Competitiveness Fund that triples apprenticeships in advanced composites or funds community-college AI boot camps would pay for itself if incremental productivity nudged GDP even 0.2 percentage points higher—enough to recoup more than the static welfare loss of current duties. WTO-consistent sectoral levies on exploitative subsidies—precisely the targeted discipline Brussels deployed against Chinese solar panels—would avoid collateral damage to consumer welfare while constraining Beijing's policy space.

Endgame: Why the Real Fight Will Be Over Productivity, Not Ports

Trade wars end when one side capitulates or both discover more efficient competing methods. The United States still commands unrivalled research universities, deep capital markets, and a currency the world trusts. China brings unmatched scale, industrial speed, and a willingness to trade margin for market share. The 90-day truce halts artillery; it does not fix the US habit of taxing its citizens to fight a battle that better-targeted tools could win. If Washington continues to treat tariffs as an all-purpose lever, stagflation and a persistent deficit will hard-code themselves into the macro landscape. But if policy pivots toward productivity—through targeted discipline abroad and skills investment at home- the subsequent ceasefire could mark a genuine turning point rather than a lull before the subsequent escalation.

The original article was authored by Samir Bhattacharya, an Associate Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi. The English version, titled "Trade war truce isn't cause for complacency," was published by East Asia Forum.