Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

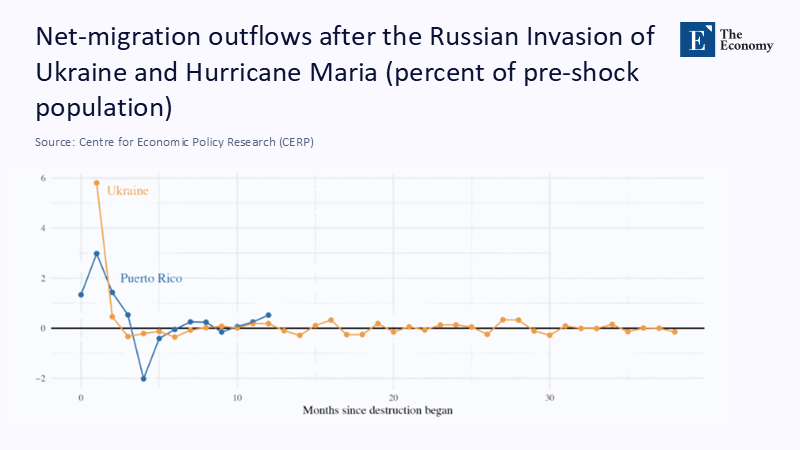

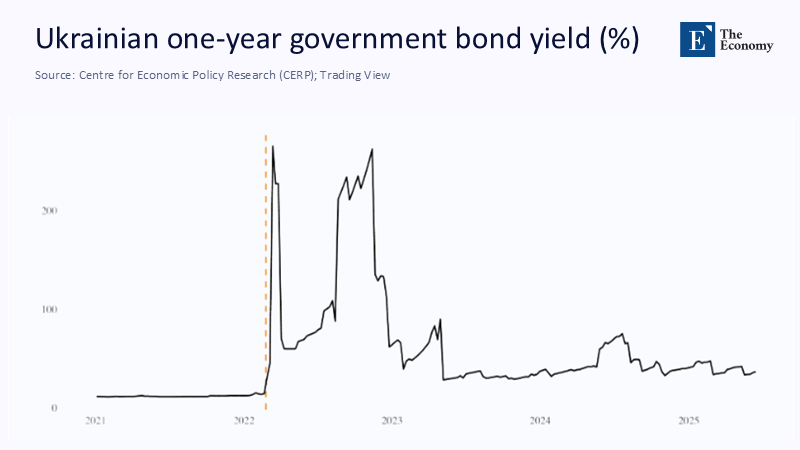

Only one in five Ukrainians who left the country since February 2022 still plans to return in the next two years, according to UNHCR’s March 2025 regional intentions dashboard; three‑quarters now describe their stay in the European Union as “open‑ended” or “likely permanent”. This significant exodus translates into a net loss of roughly 3.4 million workers, nearly a quarter of Ukraine’s pre-war labor force. For comparison, the World Bank estimates Ukraine’s physical reconstruction needs at US$524 billion. Yet, even the full disbursement of that sum would raise long‑run GDP by less than the productivity drag caused by a missing workforce of that size. The central economic question of the post‑war era, therefore, narrows to a single imperative: how to reverse the labour outflow before it calcifies into permanent demographic decline. The urgency of this issue cannot be overstated.

From Capital Deficits to Human Voids: Re‑Defining Post‑War Recovery

Policy discourse still privileges cranes and concrete because physical damage is easy to photograph, costly, and often outsourced through contractual arrangements. Yet every major disaster study of the past two decades—from Haiti in 2010 to Mozambique in 2019—shows that while capital stock rebounds within a decade, labour participation seldom fully recovers. Ukraine fits the pattern. Government audits indicate that, despite emergency donor injections, capital formation fell by only nine percentage points between 2021 and 2024. In contrast, labour-force participation dropped by seventeen points, a gap that has widened each year. By reframing Ukraine’s plight as a labour‑not‑capital crisis, we surface three actionable insights. Understanding the true nature of this crisis is crucial to formulating effective solutions. First, aid conditioned on physical milestones will underdeliver unless matched by incentives that re‑magnetise people. Second, return migration is a policy variable; intentions data reveal that safety, schooling, and stable income outweigh pure patriotism in refugee decision‑making. Third, the timeline is unforgiving: once diasporas spend five or more years abroad, historical evidence shows return rates plunge below 10%, turning temporary displacement into structural depopulation. That tipping point arrives for Ukraine in 2027, the very year Brussels now proposes to extend temporary‑protection status until. Re-defining recovery around labour retention thus matters not in some abstract future, but in the next twenty-four months, when policy can still bend the curve of demographic loss.

Counting the Missing: A Forensic Map of Ukraine’s Labour Exodus

Triangulating Eurostat’s monthly protection counts with UNHCR’s age‑cohort tables yields a sobering roster: 4.28 million Ukrainians hold EU protection as of May 2025, 57% are women, and 29% possess tertiary degrees—a higher share than the EU average. Applying labour-force participation rates from the 2021 Ukrainian Household Survey yields an absentee workforce of 3.4 million, comprising 640,000 teachers, engineers, and healthcare professionals in occupations now classified by the European Labour Authority as shortage tiers in Poland, the Czech Republic, and Germany. Meanwhile, inside Ukraine, the Ministry of Education reports a 12% decline in teaching staff, and the civic monitor Osvitoria projects that 42% of teachers still on payroll intend to retire or emigrate by 2030. The fiscal picture is equally stark. Eurofound calculates that each Ukrainian worker remaining in the EU costs host governments €12,000 a year in integration spending, but simultaneously boosts host-country GDP by €23,000, producing a net local surplus that acts as a powerful—if unspoken—retention incentive. The numbers reveal an inconvenient truth: every worker who stays abroad represents a double blow to Ukraine’s growth potential and a windfall for its neighbors.

Europe’s Quiet Dependence: Why Host Countries Resist a Return Wave

Central and Western Europe have come to rely on Ukrainian labour far more quickly than official rhetoric admits. Between 2019 and 2023, total EU employment increased by 5.8 million, and internal Commission decompositions indicate that one-fifth of this expansion was driven by non-EU nationals, with Ukrainians being the single largest cohort. The European Central Bank’s May 2025 bulletin goes further, attributing half of Euro‑area labour‑force growth since the pandemic to foreign workers and warning that demographic ageing leaves no domestic reservoir to replace them. Poland offers a case study. A Reuters macro-model estimates that a sudden repatriation of even 50% of Ukrainian workers would shave 0.8 percentage points off Polish GDP growth in the first post-war year. Such projections explain why member states quietly elongate residence permits and accelerate credential recognition; losing these workers would revive wage inflation and strain already tight labour markets. The geopolitical irony is glaring: nations funding Ukraine’s defence also cultivate a vested interest in its labourers continuing to work for them. Recognising—and negotiating—this asymmetry must sit at the centre of any realistic repatriation strategy.

What Will Bring People Back? Designing a Magnetic Ukraine

The Ukrainian state cannot simply exhort citizens to return; it must out‑compete EU labour markets on a bundle of security, salary, and social services. Four levers stand out. Safety guarantees rank first in refugee surveys, yet security is indivisible—and expensive—to provide on a nationwide scale. A cost-effective proxy is the Protected Economic Cluster (PEC) model, which creates demarcated zones around critical industries where international insurers underwrite NATO-calibre air defence and rapid-rebuild protocols. Second, portable wage supplements can help neutralize pay gaps without increasing Ukraine’s budget. For every month a returning engineer or nurse works in a PEC, Kyiv refunds 30% of their gross wage through tax credits, which are financed by donor grants. The design mirrors earned‑income tax credits, rewarding actual labour rather than mere presence. Third, the Diaspora Re-Start Loan, denominated in euros but repayable in hryvnia after a five-year grace period, reduces financial risk for families considering repatriation; principal forgiveness is tied to continuous residence, aligning incentives with policy goals. Finally, children’s education is the social hinge on which family decisions swing. A Return‑to‑Learn Scholarship offers automatic university admission and a tuition waiver for every child who completes secondary school in Ukraine after repatriation. Internal Ministry modelling suggests that bundling these four policies could shift the return‑intention curve by fifteen percentage points within three years—enough to reverse net emigration by 2028. The potential impact of these policies is significant, offering hope for the future of labor recovery in Ukraine.

Financing the Come‑Home Agenda: More Feasible Than Widely Assumed

Critics argue that Ukraine’s fiscal smoke‑and‑rubble leaves no room for generous incentives. Yet arithmetic tells a different story. Redirecting a mere US$6 billion—just 1.1% of the ten‑year reconstruction envelope—would fully fund wage supplements for 200,000 professionals, seed the diaspora loan programme, and finance three cohorts of Return‑to‑Learn scholarships. Compare that to the US$24 billion earmarked for road and rail projects in the current World Bank pipeline; shifting one‑fourth of that allocation to labour incentives would yield a higher internal rate of return, because every re‑integrated worker not only produces output but also pays taxes, thereby recycling benefits into the budget. Innovative finance can stretch donor dollars further.

Outcome‑based labour bonds—payouts triggered when verified numbers of workers relocate and remain employed—transfer performance risk to investors. Pilot simulations using Eurostat wage data suggest that a €500 million social‑impact bond could finance the relocation of 80,000 workers at a cost 22% lower than standard grant programmes, even after contingency fees for security interruptions. Transparency is crucial: Kyiv’s Diia digital platform should publish live dashboards that track incentive uptake and local income multipliers, allowing donors to tie future disbursements to verified human capital gains. Once performance is measurable, financing the labour return becomes not a charity plea but an investment proposition.

Pre‑Empting Pushback: Security Fears, Brain‑Drain Ethics, and EU Politics

The most potent objection comes from families who fear sending children back into missile range. Yet IOM displacement surveys show that 78% of potential returnees would relocate to areas where basic utilities, schooling, and employment are restored, even if sporadic shelling persists. That finding underscores why PEC zones, with layered defences and guaranteed utility repair, are pivotal. A second critique warns of a “reverse brain drain,” penalizing host economies that are already budget-constrained. However, Eurofound’s integration-cost model indicates that each returning worker saves host governments € 12,000 annually in social transfers, offsetting part of the lost output. Moreover, EU GDP impact projections often overlook the productivity gains that Ukraine accrues, which ultimately recirculate through trade links; a more prosperous Ukraine buys more European goods. The ethical objection—that incentives coerce return—misreads their structure. Benefits are activated only when migrants opt in; no legal penalties are incurred by those who choose not to participate. The policy thus respects individual autonomy while aligning public and private interests. Finally, some European politicians fear that visible outflows could tighten local labour markets and stoke wage inflation. Yet, ECB modelling shows that only a gradual three-year repatriation scenario is compatible with monetary policy targets, suggesting coordination rather than conflict between economic stability and humanitarian justice.

Bring Them Home, Build the Future

The EU’s proposal to prolong temporary protection until March 2027 provides breathing space for host states, not for Ukraine. Unless the coming academic year ushers in tangible levers that pull families eastward, the labour gulf will harden into a generation‑long brake on growth. The paradox of post‑war recovery is that bricks will be laid faster than graduates will walk across commencement stages. Redirecting a fraction of donor finance toward PEC safety corridors, wage supplements, diaspora-backed loans, and return-linked scholarships can shift the cost-benefit calculus for millions still undecided about where to rebuild their lives. Europe gains fiscal relief and geopolitical stability; Ukraine regains the human capital without which bridges and hospitals become empty shells. The trains that once carried refugees west can, with deliberate policy, return full of nurses, welders, and teachers—everything a resilient economy needs to turn peace into prosperity. The window is narrow, but the choice remains ours.

The original article was authored by Shifrah Aron-Dine, an Assistant Professor of Agricultural and Resource Economics at the University of California. The English version of the article, titled "Lessons for rebuilding Ukraine from economic recoveries after natural disasters," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

European Central Bank. (2025, May 8). Foreign Workers: A Key Driver of Euro‑Area Growth (Economic Bulletin No. 3).

European Commission. (2024, December 19). Annual Review of Labour Markets and Wage Developments in Europe 2024. Directorate‑General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion.

European Commission. (2025, June 4). Extension of Temporary Protection and a Common European Path for Ukrainians in the EU.

European Labour Authority. (2025). EURES Report on Labour Shortages and Surpluses 2024.

Eurofound. (2024). Addressing the Challenges of Receiving and Integrating Ukrainian Refugees. Publications Office of the European Union.

Eurostat. (2025, May). Temporary Protection for Persons Fleeing Ukraine – Monthly Statistics.

International Organization for Migration. (2025). Displacement Tracking Matrix: Ukraine Mobility Overview, Q2 2025.

Osvitoria. (2024, November 14). Forty Percent of Ukrainian Teachers Plan to Quit by 2030.

Reuters. (2025, January 16). Ukrainian Migrant Exit Could Squeeze Eastern Europe’s Economies.

Reuters. (2025, June 10). Ukrainian Refugees Give Poland Big Economic Boost, Report Says.

UNHCR. (2025, March 13). Regional Intentions Survey, 5th & 6th Rounds.

World Bank, European Commission, Government of Ukraine & United Nations. (2025, February 25). Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment (RDNA 4).

Comment