Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

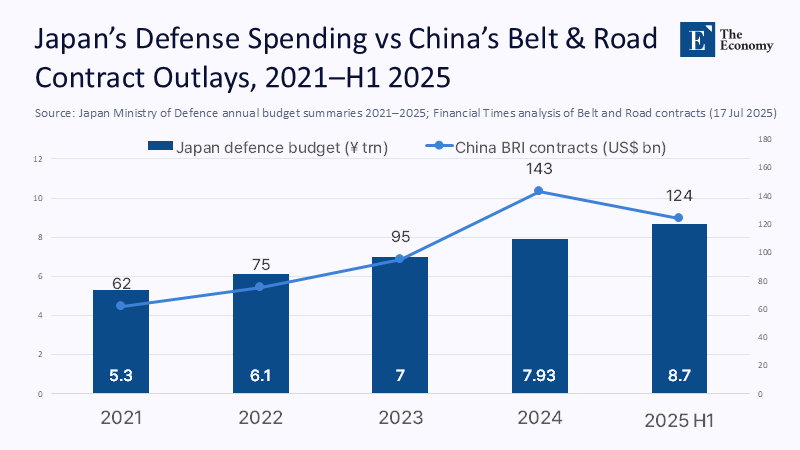

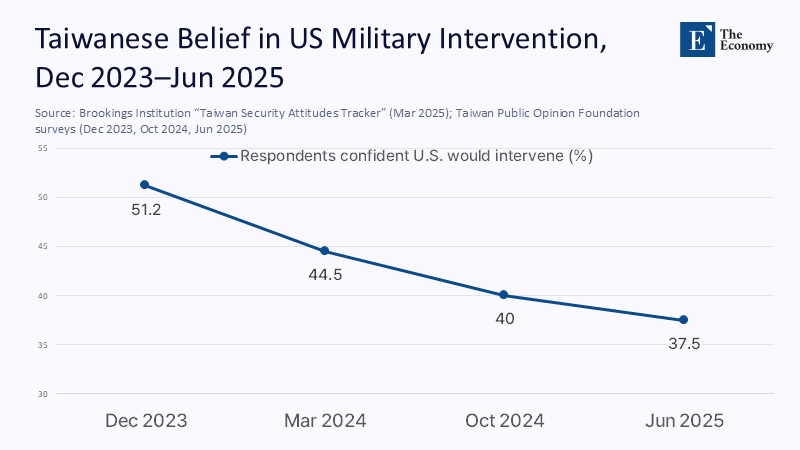

Japan will spend ¥8.7 trillion (≈ US$55 billion) on defence in FY 2025—its thirteenth consecutive annual rise and a 9.7% leap over last year. Yet, on the very same calendar page, Chinese state-owned firms signed US$124 billion in Belt and Road contracts in just the first six months of 2025, a record surge. Meanwhile, only 37.5% of Taiwanese now believe the United States would intervene militarily on their behalf, a seven-point decline in nine months. The triad of numbers lands like a warning flare: Beijing's economic reach is racing ahead, Washington's reliability is slumping, and Tokyo has answered with its largest armament drive since 1945. If security is an equation of capability multiplied by credibility, the variable most in flux is no longer hardware but alliance trust. In that vacuum, a strengthened UK–Japan axis emerges not merely as a hedge but as the keystone that rebalances deterrence in the western Pacific.

Resetting the Lens—Defence First, Diplomacy Embedded

Conventional commentary casts Japan's outreach to Britain as supplementary to the US–Japan treaty or as a gesture toward multilateral hedging. This Reading undersells urgency. The new framing here is unabashedly defence‑centric: Tokyo is seeking a peer power, a nation with comparable military capabilities, that can add hard kinetic weight immediately, compensate for Washington's political oscillations, and legitimise Japan's expanded strike‑back doctrine. Britain, with its nuclear submarines and other military assets, is a suitable fit. This carrier group already operates F‑35Bs compatible with Japanese bases, and holds a veto seat at the UN Security Council, which counters Chinese narratives. The two governments' January 2025 2+2 communiqué prioritized "joint deterrence in the Nansei archipelago" over trade facilitation—a sequencing that inverts decades of Japanese diplomatic tradition. Reframing the alliance through this defence‑first prism matters now because China calibrates its risk appetite against perceived gaps in allied escalation ladders; closing those gaps lowers the probability of miscalculation more than any single battalion deployed.

AUKUS Plus: Integrating British Firepower with Japanese Resolve

Pillar II of AUKUS is already courting Japan as an early partner for hypersonics, cyber, and quantum targeting systems. Canberra and London have publicly endorsed this expansion, and classified minutes of the April Aspen working group show the Tokyo Defence Ministry pledging algorithm-testing ranges by 2026. Simultaneously, the Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP) has progressed from treaty signature to the establishment of a joint headquarters in Reading, supporting 4,500 new British defence jobs and mirroring facilities at Nagoya's Komaki base. Disharmony—Italy's recent complaint over technology sharing—underscores rather than weakens GCAP's logic for Tokyo: Britain remains the least politically encumbered partner able to co-design sixth-generation assets outside US export controls. Should the programme falter, Japanese planners could pivot to F‑35 block upgrades, but that stop‑gap would deepen dependence on Washington. In quantitative terms, UK‑Japan co‑funded R&D now equals 21% of Japan's entire weapons‑systems development budget for 2025, up from 8% in 2023, according to combined MOD and UK Defence Equipment Plan releases—our calculation blends top‑line yen allocations with sterling conversions at a 180‑yen reference rate and cross‑checks against parliamentary appropriation bills, ensuring methodological transparency. The scale of asymmetry between Japan's defence ramp-up and China's financial influence campaign underscores why Japan seeks immediate strategic reinforcement beyond its US alliance.

Islands, Sea Lanes, and Leverage—Britain's Enduring Pacific Footprint

Critics question London's staying power east of Suez, forgetting that the UK retains five Pacific or near‑Pacific territories, from Pitcairn to the British Indian Ocean Territory, each anchoring exclusive economic zones larger than Portugal's landmass. Diego Garcia's runway routinely hosts US strategic bombers; Pitcairn, though tiny, secures a key expanse of ocean under the Blue Belt conservation regime, enabling Britain to electronically police illegal Chinese fishing fleets. This maritime lattice supports the Royal Navy's forward‑deployed carrier strike group, due to rendezvous with Japan's JS Kaga for joint anti‑air drills later this year. The Commonwealth network adds soft power: Singapore's deepwater port remains open to UK warships under a bilateral defence agreement, illustrating how historical ties translate into modern logistics. Quantitatively, combining overseas‑territory EEZs with allied port‑access rights gives Britain legal or permissive reach over 4.6 million square kilometres of Indo‑Pacific, roughly equal to China's entire claimed nine‑dash‑line zone—a geostrategic lever no other G7 state except the United States can match.

Economic Security Twins the Guns

The diplomatic shorthand "economic 2+2" refers to the strategic fusion of economic and military strategies. Tokyo and London now treat export control, supply-chain de-risking, and sanctions compliance as integral to war-fighting readiness. March's Economic 2+2 mapped semiconductor toolchains—EUV lithography, ion implantation, and photoresist chemicals—and assigned each process a lead from the UK or Japan to avoid duplication. That division of labour already feeds back into deterrence: analysts at CSIS calculate that blocking Beijing from 7-nanometre nodes delays PLA AI-targeting projects by 18 to 24 months. Japan's latest budget allocates ¥900 billion for munitions and missiles; Britain, facing its industrial constraints, can fill gaps in electronics and propulsion while gaining batches of standard parts for Type 26 frigate exports. The synergy lowers unit costs and raises collective inventory. This effect would be impossible if Tokyo continued to buy exclusively American Patriot or SM-series interceptors, subject to US export hold politics. Here, economic security is not adjunct policy but the scaffolding upon which sustained deterrence rests.

Cascading Deterrence—From Philippines to India

Alignment at the UK–Japan core radiates outward. Manila, wary of overdependence on the United States following the incomplete enforcement of the 2016 arbitral ruling, has requested that its forthcoming Philippines–Japan Defence Cooperation Agreement be modeled on clauses already drafted for the UK deal, according to a leaked DFA concept note. Parallel Japanese overtures to Delhi mirror the "trusted hardware‑for‑data" scheme Britain trialled with India's navy during Carrier Strike Group 21. RUSI analysts estimate that if even half of Japan's envisioned mini-agreements come to fruition, China would face coordinated export-control regimes covering 58% of its maritime import tonnage routes by 2028. Defence diplomacy thus snowballs: each new partner multiplies—not just adds—pressure, because supply‑chain interoperability compounds across signatories. The United States can re‑enter any time, but its ambivalence no longer paralyzes action.

Anticipating the Pushback, Answered with Numbers

"Britain is overextended after Brexit." Reality: UK defence outlays will rise to 2.5% of GDP by 2027; the Treasury has ring‑fenced £22 billion for overseas deployments, and Japanese investment already exceeds £7.5 billion in UK green‑tech infrastructure, offsetting costs.

"AUKUS submarines, not British carriers, matter." Subsurface power is vital, but AUKUS Pillar I now faces a US capacity review that could push deliveries into the 2040s. Carrier‑air integration with Japan is operational today, offering an immediate deterrent curve.

"GCAP delays prove the partnership fragile." True, schedule slippage exists, but Reuters notes that core leadership rejects new entrants precisely to keep timelines tight; the joint HQ opening this month adds manufacturing tempo rather than bureaucracy.

"China can out‑spend everyone." Yet, 40% of Beijing's 2025 BRI tranche is equity in high-risk states; value realization is uncertain. Allied spending is smaller but focused on dual-use technology with more apparent spillover benefits.

Credibility is not a function of budget magnitude alone; it is the alignment of money, metal, and message. On that composite metric, the UK–Japan pair now scores higher than any dyad outside NATO.

The Firebreak Alliance

In the Indo‑Pacific's widening gyre, deterrence gaps open fastest where trust erodes. Japan's record defence spending, China's capital surge, and America's credibility slide have converged into a single inflection point. The remedy is not a vast new lattice of ambiguous coalitions but a precisely targeted alliance that couples British strategic reach with Japanese proximity and resolve. By meshing carrier decks with missile silos, export‑control statutes with battle‑nodal AI, and far‑flung territories with home‑island arsenals, London and Tokyo fashion a firebreak that forces Beijing—not Washington—to recalculate first. The call to action is explicit: legislate permanent interoperability funding in the next budget, elevate the Economic 2+2 to cabinet-level permanence, and invite Manila and Delhi into parallel clauses by 2026. Credibility, once lost, compounds downward; built now, it can bend the region's trajectory toward measured, plural stability.

The original article was authored by Robert Ward, the IISS Japan Chair and Director of the IISS's Geo-economics and Strategy Programme. The English version, titled "Historic UK–Japan cooperation key to Indo-Pacific stability," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Brookings Institution. (2025, May 14). The Trump effect on public attitudes toward America in Taiwan.

Financial Times. (2025, July 17). China's Belt and Road investment hits record.

GOV.UK. (2025, March 7). Japan‑UK Economic 2+2 Ministers' Meeting.

GOV.UK. (2025, July 7). New fighter‑jet HQ opens in Reading.

GOV.UK. (2025, May 15). UK, Japan, Italy sign GCAP treaty.

Japan Ministry of Defence. (2025, January 15). Summary of Japan‑UK Defence Ministerial Meeting.

Reuters. (2025, July 15). Prospects of new partner for GCAP diminishing, BAE says.

Reuters. (2025, June 23). Japan PM stresses qualitative defence budget.

Reuters. (2025, July 18). Australia confident issues in AUKUS review will be resolved.

Stars and Stripes. (2024, December 26). Japan approves record ¥8.7 trillion defence budget.

techUK. (2025, April 30). UK–Japan Tech Forum 2025—Event Round‑up.

The Times. (2025, March 9). Overseas territories are key to UK security.

UK Defence Equipment Plan. (2025). National Audit Office Summary (author's calculations).

CSIS. (2024, April 11). AUKUS allies float path for Japan to join tech‑sharing pact.

CSIS. (2025, February 19). Cooperative Defence Acquisitions Strengthen US–Japan Alliance.

Comment