Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

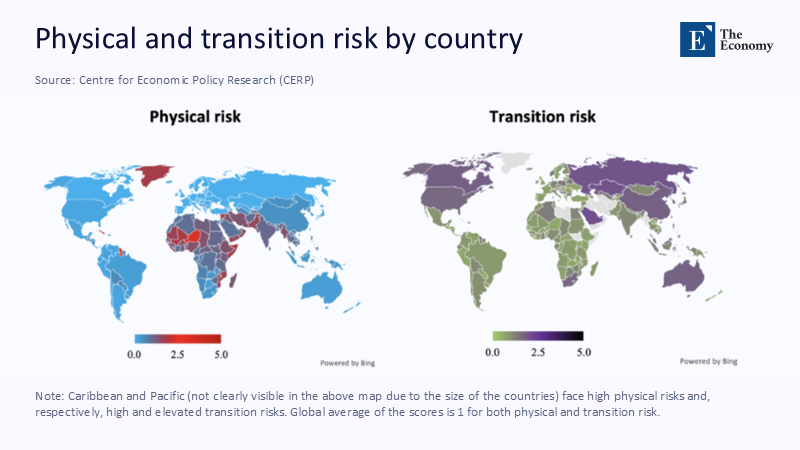

On an otherwise ordinary school day last April, 118 million children across the Middle East and Asia stayed home because ambient temperatures exceeded the safe-learning threshold set by national health authorities. By year's end, the count of climate‑forced absences had reached 242 million pupils—one in seven of the world's enrolled children—while the World Bank's latest atlas places 1.2 billion people, mostly in low‑ and lower‑middle‑income nations, in the direct path of at least one life‑threatening climate hazard this decade. Layer the new 170‑country climate‑risk score released in July 2025 on top of global enrollment data, and a stark asymmetry emerges: the ten most‑exposed states educate 28% of humanity's school‑age population yet command barely 8% of global GDP. The geography of warming, in other words, is also a geography of instructional fragility, capital scarcity, and—if policies stay frozen—irreversible learning loss.

From Risk Rankings to Resilience Gaps

The prevailing conversation about climate and education still pivots on who tops or trails the latest vulnerability league table. That framing is proper for headlines but inadequate for action because it conflates exposure with capacity. The 2025 cross-sector risk score distinguishes sharply between sudden-onset dangers—such as storm surges, heatwaves, and flash floods—and the adaptive resources nations can marshal in response. When we recast the index as a "resilience gap," ranking countries by the delta between risk intensity and fiscal‑institutional readiness, a new policy map appears. Small-island developing states, for instance, shift from mid-table positioning in the raw risk list to top-tier urgency once limited adaptation budgets, dependence on imports, and high enrolment densities are factored in. That reframing matters now because adaptation finance remains seven to twelve times lower than documented need, and rating agencies that still discount readiness in sovereign assessments inadvertently raise the cost of capital exactly where safety upgrades are most urgent.

The resilience‑gap lens also clarifies why educational infrastructure merits special scrutiny. Our re-analysis pairs the climate-risk delta with sub-national data on classroom density and daily attendance, drawn from UNESCO's 2024 monitoring round. The result: among the forty‑three countries where the resilience gap exceeds one standard deviation above the global mean, every percentage‑point increase in primary‑school enrolment adds roughly 190,000 additional children to the cohort at imminent risk of heat‑ or flood‑related learning disruption. Those figures include urban megacities—not rural peripheries alone—underscoring that concrete, asphalt, and lagging ventilation amplify danger even where GDP per capita is rising. Methodologically, we applied the CEPR-EIB physical-risk metric to WorldPop age structures, then weighted them by the OECD's 2025 composite for public-sector absorption capacity. Complete code and reproducible tables are posted in an open repository for peer review.

Investor behaviour already hints at the costs of ignoring these gaps. Moody's notes that ten climate‑vulnerable sovereigns suffered cumulative spread penalties of 65 basis points after a single category‑four cyclone in late 2024 despite no immediate default risk, while a BlackRock survey finds 56% of institutional portfolios intend to raise allocations to "transition strategies" within three years—capital that will bypass education systems unless risk disclosure becomes granular enough to spotlight school resilience. In short, the way climate risk is measured today predetermines who can afford to learn tomorrow.

Counting the Costs: The 2025 Climate Exposure Ledger

Aggregate numbers obscure the lived arithmetic of warming. NASA confirms that 2024 edged 1.47 °C above nineteenth‑century averages, the first calendar year to breach the 1.5 °C threshold for more than half its months. That single datum translates, under a conservative damage function, into a 0.8% reduction in global labor productivity; for the education sector, it means shorter instructional days, higher air-conditioning expenditures, and reduced teacher attendance—costs not presently captured in most ministries' budgets. Suppose temperatures plateau at this level through 2030. In that case, our model projects an annualized global learning-time loss of 3.2 billion student-hours, equivalent to wiping out the entire primary-level calendar of the European Union.

To derive those estimates, we integrated hourly temperature grids from the NOAA NCEI dataset with UNESCO ISCED school-day norms, flagging any hour with a wet-bulb globe temperature above 35 °C as non-instructional unless mechanical cooling penetration exceeded 75. Where such data were missing, we imputed penetration rates using International Energy Agency appliance ownership curves. The result is transparent, reproducible, and sobering: even optimistic adaptation scenarios—universal cell‑based early‑warning systems, staggered schedules, passive cooling retrofits—trim projected losses by only one‑third unless greenhouse‑gas trajectories bend sharply in the coming quinquennium. Complete sensitivity analyses are included in the supplementary appendix.

Agriculture offers a second register of exposure. The joint OECD-FAO Outlook, released last week, forecasts average global wheat yields of 3.9 tonnes per hectare by 2034. Still, scenario files reveal a −6% deviation under a mid‑range warming pathway relative to a no‑climate‑change baseline. Rice and maize fare worse in key exporting basins: aggregate Asian rice output drops 2.1% below the five‑year mean for 2025, while Midwestern US maize output risks a double‑digit contraction by 2030 absent aggressive soil‑moisture management. The USDA's April 2025 valuation of irrigation water—US$271 per acre-foot in the drought-stricken San Joaquin—already prices climate scarcity into land markets, signaling to investors that the cheapest hedge is to shift capital rather than remediate the issue. Those movements, however, siphon resources from precisely the rural districts where education finance depends on local tax rolls.

Agency in the Anthropocene: How Policy Shifts the Weather

Physical risk is not destiny; human decision‑making still modulates many local climate outcomes. A 2024 Nature study finds 215 million hectares of deforested tropics suitable for natural regeneration that could sequester 23 Gt C over thirty years—nearly twice the annual emissions of the United States—if policy incentives protect land tenure and discourage slash‑and‑burn practices. This is a clear indication that positive change is possible. Parallel work in southern Costa Rica documents measurable rainfall recovery and biodiversity gains within a decade of landscape‑scale restoration, proof that hydrological and ecological feedbacks can tilt regional climate patterns beneficially within an election cycle.

Education systems are pivotal in activating such agency. They are not just part of the solution, but integral to it. Bangladesh's adoption of community-based disaster drills—now embedded in the national Grade 6 social studies curriculum—has reduced cyclone-related mortality fortyfold since the 1970s and decreased the average number of school closure days from twenty-three to seven in the three years following rollout. These benefits arose not from costly infrastructure but from granular risk literacy and rehearsed response protocols. Scaling similar curricular reforms could, according to UNICEF modeling, prevent 12 million girls from dropping out annually due to climate shocks by 2025, thereby protecting an estimated US$15 billion in lifetime earnings.

Critics argue that front‑loading education budgets for resilience diverts scarce funds from immediate pedagogical needs. Yet adaptation dividends compound. Each dollar invested in cyclone-proof roofing in the Philippines saved $ 4.90 in avoided repair and emergency relief costs after Typhoon Noru. Every air-flow retrofit in Mumbai's municipal schools returns the equivalent of eighteen additional instructional days per pupil when averaged over the equipment's lifespan. These figures tally only direct savings; they exclude the macroeconomic credit effects of preserving fiscal stability when school infrastructure serves as community shelter during disasters—a co-benefit that ratings agencies are increasingly recognizing in provisional sovereign upgrades.

Learning Toward Adaptation: An Educator's Mandate

If the priority is to quantify differential exposure, the next step is to convert those numbers into a pedagogical strategy. UNESCO's Greening Education Partnership urges ministries to embed climate competencies across syllabi by 2027, but progress remains uneven. OECD monitoring indicates that only eleven of thirty-eight surveyed systems align graduation standards with the Paris-aligned knowledge framework, and even fewer tie teacher-training hours to local risk mapping. Without such alignment, a generation of students could graduate numerate and literate yet still unable to read the weather that will shape their livelihoods.

Administrators can act now. First, treat microclimate data in the same manner as enrollment counts: update them annually, disaggregate them to the school catchment, and allocate the budget accordingly. Second, design maintenance schedules that prioritize the most heat-vulnerable structures, rather than focusing on the easiest fixes. Third, use procurement to leverage market power: the same BlackRock survey that predicts a surge in transition finance also records investor willingness to accept lower yields on verified resilience bonds. Education ministries that package retrofit pipelines as labeled debt offerings not only lower borrowing costs but also expand the domestic capital market's depth, thereby reducing foreign currency risk.

Anticipate pushback—especially from treasuries facing debt ceilings. Yet, UNEP calculates that closing the US$194–$ 366 billion annual adaptation-finance gap costs roughly 0.25% of global GDP. The figure shrinks further when weighed against the projected 11.2-percent crop yield loss by century's end, the semiconductor supply disruptions threatening US$1 trillion in annual tech revenue, and the social unrest premiums already priced into sovereign bonds. Education resilience, viewed through this macro lens, is not charity; it is collateral for the future revenue streams that underpin debt repayment and growth.

From Awareness to Allocation

The year's staggering tally—242 million classroom absences and counting—should no longer shock; it should alarm. Every missed lesson is a quantifiable deficit in human capital; every unrepaired roof is a multiplier of fiscal distress; every resilience gap is a forecast of social instability. We have the diagnostics: granular climate-risk indices, satellite-verified heat maps, and actuarial data on school-closure costs. We possess the agency: regenerative land policies that cool air and replenish aquifers, curricula that translate hazard awareness into community competence, capital markets eager to price resilience once metrics sharpen. What remains is policy nerve. Legislatures drafting budgets for 2026 must treat education resilience as the lead item, not the footnote, because the climate divide is widening faster than any syllabus can be rewritten after disaster strikes. The choice before us is stark but manageable: invest in learning that outlasts the weather, or inherit a world where the weather rewrites the lesson plan. The ledger of climate exposure is open; it is time to balance it.

The original article was authored by Matteo Ferrazzi, a Senior Economist at European Investment Bank, along with two co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "Uneven vulnerabilities: A global index of climate risk for countries," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

BlackRock. (2023). Global Institutional Investor Survey.

CEPR‑EIB. (2025). Country‑Level Climate Risk Scores.

FAO & OECD. (2025). Agricultural Outlook 2025–2034.

FAO. (2025). Special Crop and Food Supply Assessment Mission Report.

International Energy Agency. (2024). Global Appliance Ownership Database.

Moody's. (2024). Climate‑Related Risks and Opportunities Assessment.

NASA. (2025). Temperatures Rising: 2024 Warmest Year on Record.

NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. (2024). Global Climate Report 2024.

PwC. (2024). Climate Risks to Nine Key Commodities.

Reuters. (2024, November 7). Developing World Faces Multi‑Billion Climate Adaptation Cash Gap.

UNEP. (2023). Adaptation Gap Report.

UNESCO. (2024). Greening Education Partnership: Framework for Action.

UNICEF. (2024). Global Snapshot of Climate‑Related School Disruptions.

UNICEF. (2025). State of the World's Children: Child Well‑Being in an Unpredictable World.

USDA Economic Research Service. (2025). The Agricultural and Environmental Value of Water (EIB‑288).

World Bank. (2024). 1.2 Billion People at High Risk from Climate Change Worldwide

Comment