Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

“When a city’s dams run dry, the first thing to vanish is the illusion that scarcity is shared.” This stark reality underscores the urgent need for action in the face of water scarcity and its unequal impact on society. Cape Town’s hair-raising sprint toward “Day Zero” in 2018 showed that a climate shock does not simply reduce the water in a reservoir; it rearranges the moral architecture of the city that drinks from it. While the middle classes tightened garden hoses and tourist brochures discreetly trimmed poolside photos, residents of the city’s informal settlements queued before dawn for plastic jerrycans, hoping the standpipes had not been closed overnight. That contrast, repeated in drought-stricken communities from Chennai to Monterrey, exposes a blunt truth: climate hazards amplify whatever hierarchy they encounter. Re-examining Cape Town’s near-catastrophe six years later, with fresh micro-data and hydrological readings now available, is, therefore, more than a historical exercise; it is a blueprint for how inequality mutates in real-time when the climate throws its most brutal punch—and a call to action for every education ministry that depends on stable public utilities to keep schools open, urging them to seek equitable solutions.

Drought’s Social Geometry: How a Meteorological Accident Became a Moral Reckoning

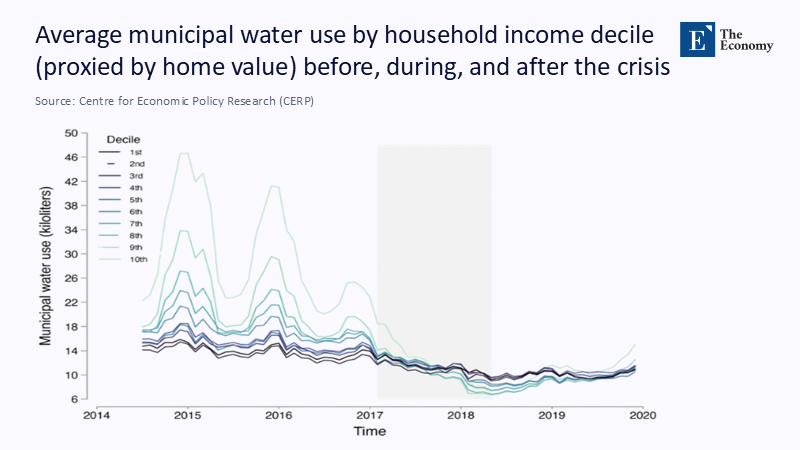

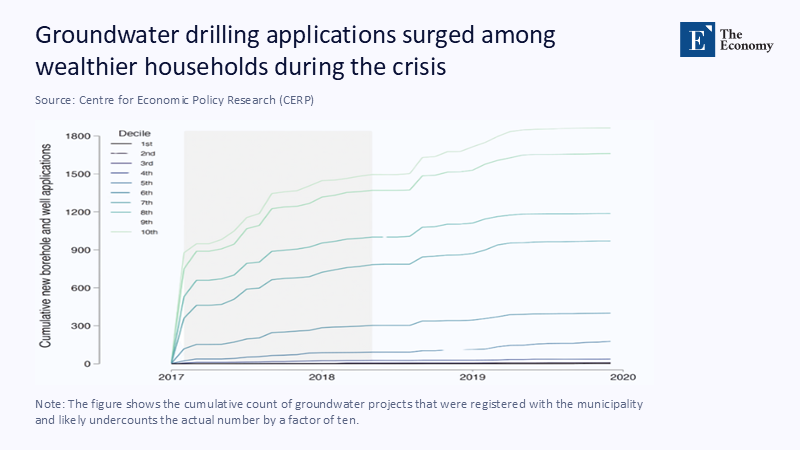

Between 2015 and 2018, rainfall over the Western Cape fell to less than 60% of its twentieth-century mean. The six feeder dams that normally glint on postcards plummeted from 95% capacity to a surreal 13.5%—one-tenth of the volume needed to guarantee continuous flow to household taps. That hydro-logical statistic is well known; less discussed is that Cape Town entered the drought already split by a Gini coefficient above 0.63, one of the highest in the world. When the city imposed escalating block tariffs, a water pricing system where the cost per unit of water increases as the volume used increases, wealthier neighborhoods responded with brisk efficiency, ripping up lawns, retrofitting dual-flush toilets, and—most crucially—drilling an estimated 15,000 private boreholes, ten times the number officially registered. What looked on paper like civic solidarity—aggregate municipal demand fell by half—concealed a subterranean fissure. The aquifer risk was exported to the ex-urban water table, while the public-revenue risk was imported wholesale into the city budget. Engineers quietly reported that groundwater withdrawals in the well-heeled suburbs had depressed local tables by up to six meters, raising salinity levels for peripheral farming communities that lacked the capital for deeper drilling.

Counting Drops: The Hidden Arithmetic of Scarcity and Class

Cape Town’s census-linked billing files reveal that before the crisis, the richest decile consumed an average of 2,100 liters per day—enough to fill a midsize pickup bed—while the poorest three deciles combined used barely 450 liters, little more than the volume of a commercial beer keg. Under emergency restrictions, low-income families pushed usage below 85 liters per household daily, undercutting the World Health Organization’s humanitarian threshold for basic sanitation. The wealthy, by contrast, cut demand for municipal water by a dramatic 46%, yet their private boreholes kept total household availability north of 1,100 liters. That is the uncomfortable arithmetic of elasticity: one group sacrificed necessity, the other sacrificed convenience.

Worse, Cape Town’s tariff structure relied on high-volume users to contribute 61 % of total revenue, which underwrote lifeline blocks for people experiencing poverty. Once affluent households abandoned the grid, volumetric revenue fell by R 1.7 billion in twelve months, forcing the utility to raise fixed charges on all connections. This tacit tax hit prepaid-meter townships hardest. In effect, private adaptation operated like a regressive value-added levy collected not at the point of purchase but at the point of survival.

Boreholes and Bottom Lines: When Private Resilience Morphs into a Public Liability

Drilling a legal borehole in Cape Town cost between US $3,000 and US $10,000 in 2018. Each household that tapped the Table Mountain Group aquifer reduced its municipal bill by roughly 70%, depriving the city of the cross-subsidy that had kept water affordable for 400,000 low-income customers. Faced with a budget crater, the municipality rushed through a redesigned tariff: a stepped fixed fee tied to pipe diameter, calibrated so that a four-inch connection in a gated community paid thirty times the flat fee levied on a two-inch pipe in a working-class suburb.

Even this political sleight of hand barely closed the gap. Internal memos leaked in 2020 show the water department contemplating suspending maintenance at 237 schools if reserve funds fell below 5% of operating costs. The episode crystallizes a general rule for climate economics. Whenever affluent consumers can unbundle a public service into a private workaround, the state is left shouldering the fixed costs of universality without the revenue from volume. That dynamic, already destabilizing electricity markets in California and telecom networks in Nigeria, now stalks every utility threatened by extreme weather.

The Adaptation-Finance Mirage: Global Numbers, Local Consequences

Cape Town’s ledger is a microcosm of the planetary balance sheet. According to the United Nations Environment Programme, international public flows for adaptation rose from US $22 billion in 2021 to $28 billion in 2022, the most significant one-year jump since Paris. Yet even if developed nations honor their Glasgow promise to double such finance by 2025, the annual need, now pegged between $187 billion and $359 billion, would be met only 5% faster than today’s glacial pace. In other words, the world is funding adaptation for the vulnerable at eight cents on the dollar. This mirrors Cape Town’s household paradox: the liquidity necessary for resilience accrues to those already cushioned by capital. Without radical changes in how money is raised (progressive carbon levies, climate-damage taxes) and who controls its deployment (local authorities rather than donor consortia), global adaptation will continue to replicate, rather than redress, the inequalities exposed by every drought.

Education on the Edge: Why Water Scarcity Funnel Through the School Gate

For an education journal, the connection between boreholes and textbooks might seem remote—until one tracks the ripple. During Cape Town’s restrictions, 91 public schools exhausted their daily allocations before the lunch bell; at least 27 sent pupils home two hours early, for a cumulative loss of 9,000 instruction hours in the first quarter of 2018 alone, according to provincial audits. Internationally, UNICEF estimates that climate-related hazards—including drought-triggered water cuts—disrupted learning for 242 million students in 2024, more than the combined primary-school populations of the United States, Brazil, and Nigeria. Girls shoulder the heaviest burden: where standpipes run dry, menstrual hygiene management becomes impossible, and dropout rates spike. A study across 26 African countries finds that households facing chronic water scarcity report school attendance rates nine percentage points lower than similarly situated households with reliable taps. The vicious circle is well documented: missing school reduces lifetime earnings, lowering the tax base available for future infrastructure, setting the stage for the next crisis.

Designing Equitable Adaptation: From Utility Tariffs to Classroom Faucets

What, then, does a just adaptation formula look like? First, tariff design must acknowledge that volumetric pricing collapses under extreme conservation. Cape Town’s fix—graduated fixed fees indexed to property-value proxies—offers a template, but only when paired with ring-fenced exemptions for essential social services. Every school meter should be coded as “critical infrastructure,” shielded from cut-offs until the household and commercial demand in affluent zones has been curtailed to the same physiological baseline. Second, private wells and rain-harvesting systems need a regulatory envelope on par with building codes: mandatory licensing, extraction caps, and remote-sensing audits financed by a hypothecated levy on drilling contractors. Third, national governments should make a progressive revenue architecture a precondition for receiving international adaptation loans. In doing so, equity shifts from moral garnish to financial covenant, altering project bankability in the same way anti-corruption clauses currently shape development lending. Finally, data transparency matters. Real-time dashboards—updated every 24 hours—should display consumption and borehole counts by census tract, allowing parents, principals, and civil society groups to pressure officials before classrooms go dark.

A Curriculum of Resilience: Teaching Climate Inequality Before It Teaches Us

Cape Town’s drama belongs not only in engineering textbooks but also in civics classrooms, economics modules, and teacher-training colleges. Students who model the drought’s tariff scenarios learn more than supply-and-demand curves; they confront the ethical calculus of who can flush twice and wait in line. Incorporating case-based pedagogy—with anonymized billing data now publicly available—equips future educators to trace the compounding effects on attendance, nutrition, and psychosocial stress. Academic publishers should act quickly to commission interdisciplinary materials: one chapter on hydrology, another on public finance, a third on gendered impacts of WASH deficits, and a capstone policy lab where pupils design a drought-response blueprint for their city. That approach peels climate change away from abstraction. Instead of polar bears and melting ice, teenagers grapple with whether the school’s toilets will flush tomorrow. Pedagogically, the immediacy galvanizes civic participation; politically, it seeds a voter base fluent in the distributional stakes of adaptation.

Toward a New Social Contract of Water and Learning

Cape Town’s brush with Day Zero did not end in a humanitarian meltdown. The lights stayed on; the taps, mostly, kept dribbling. But the episode lifted a veil. It demonstrated that water scarcity is not a simple subtraction problem—rainfall minus consumption—but a multiplication of privilege minus regulation. The same principle applies globally: without deliberate, equity-centered policy, the money and technology that make households safer will flow uphill, while the social costs will cascade downward into the classrooms of low-income people. The next great drought—whether in São Paulo, Los Angeles, or Accra—will test whether we have learned Cape Town’s lesson: every liter diverted into a private well must be matched by a liter of public accountability, and every adaptation dollar must be audited for its impact on the child who cannot afford to miss another day of school. Anything less is not adaptation; it is abdication.

The original article was authored by Alexander Abajian, a Ph.D. Student at University of California. The English version of the article, titled "Climate adaptation and inequality: Lessons from Cape Town’s drought," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Abajian, A. C. et al. “Climate adaptation and inequality: Lessons from Cape Town’s drought.” VoxEU/CEPR (12 June 2025).

ActionAid UK. “Climate Change and Poverty” (accessed 13 June 2025).

Frontiers in Education. “Climate Change Injustice and School Attendance” (Dec 2024).

Knowledge Economy Journal. “Impact of Water Scarcity on Education Outcomes: Evidence from 26 African Countries” (Dec 2024).

UNICEF. Global Snapshot of Climate-Related School Disruptions 2024 (Jan 2025).

United Nations Environment Programme. Adaptation Gap Report 2024: Come Hell and High Water (7 Nov 2024).

World Bank. Water for Shared Prosperity Press Release (20 May 2024).