Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

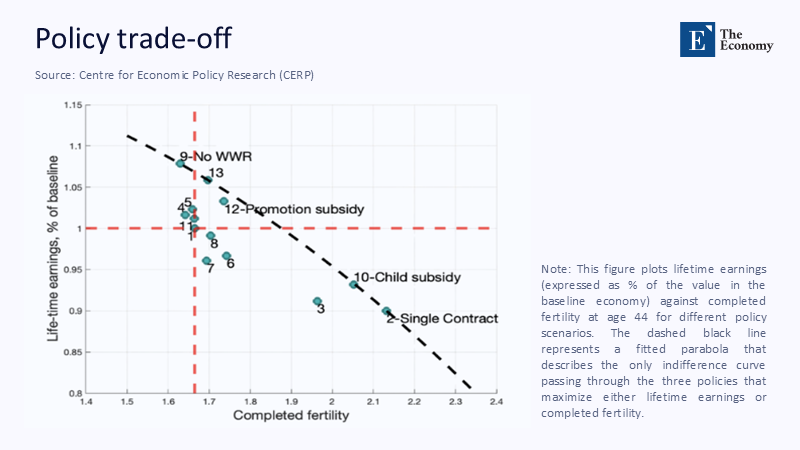

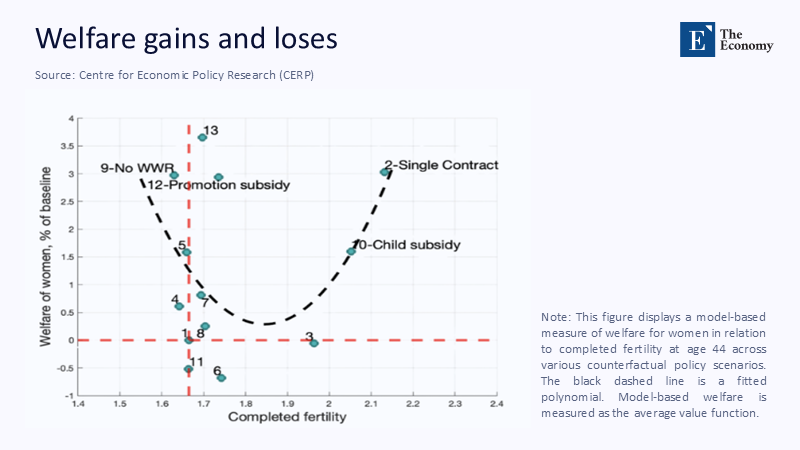

In 2023, the European Union's total fertility rate fell to 1.38, the lowest on record. On the other side of the Atlantic, the United States registered 3,628,934 births in 2024—up 1% from 2023—even as the general fertility rate slipped another 1% to 53.8 births per 1,000 women aged 15–44. Meanwhile, the infant–toddler childcare crisis alone drains an estimated $122 billion each year from U.S. earnings, employer productivity, and tax revenues. These figures do not merely describe demographic headwinds; they quantify the operating constraints under which firms make staffing and promotion decisions. Suppose the goal is more births without arresting women's career progress. In that case, we should stop paying for promotions and start paying to prevent costly exits, smooth returns to role, and build capabilities that managers recognize as durable productivity. Promotion subsidies send a fuzzy signal. Retention‑first design speaks the language of the P&L and sticks.

Shifting the Policy Focus: From Symbolic Promotion to Measurable Productivity

A popular response to the career "child penalty" is to subsidize promotions for parents, reasoning that firms under‑promote women when they anticipate leave or part‑time requests. The instinct acknowledges an inconvenient truth: firms respond to incentives, and well‑meaning protections can backfire. Spain's 1999 reform, granting part‑time rights with strong employment protection, offers a cautionary example. Because women disproportionately used the right, some firms adjusted by reducing promotions to permanent contracts for women of childbearing age, an unintended consequence of policy that altered costs without addressing capability or predictability. This is not an argument against rights; it is an argument for aligning them with the internal economics that drive managers' decisions.

If we take firm behavior seriously, the policy aim should shift from purchasing titles to purchasing time, predictability, and capacity. Promotions are the culmination of credible performance signals and stable contribution. They cannot be mass‑produced by fiat without distorting the very signals that make them plausible. Paying a bounty for the event—"promote and collect"—invites moral hazard and the perception that advancement is less earned. Funding return‑to‑role stability and capability‑building milestones not only reduces departure risk but also makes the next promotion a consequence of genuine productivity rather than a subsidized outcome. Policy should buy the inputs firms value—retention and skill growth—because managers will keep paying for those long after the subsidy sunsets.

What the newest numbers say—and how to read them responsibly

The demographic context is unambiguous across advanced economies. In the OECD, average fertility hovered around 1.5 in 2022, with Italy and Spain near 1.2 and Korea at roughly 0.7 in 2023. Within the EU, the 1.38 figure for 2023 underscores a structural slide, not a fleeting blip. The U.S. picture combines a slight rise in births with a continued drop in the general fertility rate—signals of shifting timing and desired family size rather than a simple cyclical dip. This is the landscape into which any pro‑family labor policy must be projected; pretending that a single lever (like subsidized promotions) can reverse structural demography mistakes the scale of the problem.

Behind the aggregate trends sits the most robust micro‑evidence we have: the child penalty opens at first birth and persists. Across 100‑plus countries, women and men track similarly before parenthood, then diverge in employment and earnings as mothers experience steeper and longer interruptions. That divergence is not pure bias; it reflects concrete frictions—unreliable child care, unpredictable scheduling, and role re‑entry barriers—that degrade observed productivity in the months and years after childbirth. Firms internalize those expected costs when they set sponsorship, promotion, and backfill budgets. If policy dollars lower the frictions that managers price, promotion rates rise without needing a bounty.

To keep the evidence honest, we anchor our estimates in conservative ranges. Turnover costs average about 33% of base pay across roles, with credible role‑specific forecasts around 40% for frontline staff, 80% for technical roles, and ~200% for leaders and managers. We combine those cost ranges with documented changes in promotions after Spain's reform to stress‑test the ROI of alternative designs. Where numbers are uncertain, we show our math: lower turnover costs weaken the case for retention subsidies; higher costs strengthen it. The point is not to make the spreadsheet drive the story; it is to let the operational arithmetic discipline our policy imagination.

The economics that move managers: retention beats purchased promotion

Managers live in present‑value math. An avoidable exit today means months of vacancy, recruiter fees, onboarding drag, risk to customer relationships, and the silent costs of lost tacit knowledge. When a policy reduces expected turnover among new parents—by securing childcare access, guaranteeing a predictable return‑to‑role ramp, or underwriting temporary backfills—its benefits appear almost immediately in unit budgets. A promotion subsidy, by contrast, pays once for a label without necessarily changing the risk that the newly promoted employee burns out or steps back under continuing strain. If the exit still happens, the subsidy merely cushions a short‑lived signal while leaving the productivity problem intact. It is better public finance—and better management—to buy the risk reduction.

A stylized calculation clarifies the difference. Consider a mid‑career professional earning €70,000. If the average avoidable‑turnover cost is one‑third of pay, each departure costs roughly €23,000. Suppose a retention‑first package—predictable scheduling rights, a return‑to‑role guarantee, and partial childcare stipend—reduces exit risk among new parents by 10 percentage points over two years in a cohort of 100 such employees. Expected savings: 10 × €23,000 = €230,000, before any value is placed on preserved project knowledge. Now, assume a promotion subsidy of 10% of salary for one year for parents promoted within 24 months of birth. If 15 promotions qualify, the outlay is €105,000, which looks cheaper in isolation. But if even five of those promotions are undone by strain or exit, the savings evaporate. The policy that wins on risk‑adjusted ROI is the one that stabilizes employment.

What should educators, administrators, and policymakers do with this evidence?

For educators preparing the next cohort of leaders, the charge is to teach promotion‑process design with the same rigor as finance or operations. Evidence from the "broken rung" shows that early career progression is the choke point: in 2024, for every 100 men promoted to first‑line manager, only 81 women were. That disparity compounds over time. Curriculum should therefore emphasize structured promotion criteria, blind or anonymized review of performance dossiers where feasible, and calendar‑fixed promotion windows so that parental leave timing does not become an unspoken penalty. Embedding these practices in MBA and executive education builds a managerial pipeline that does not need a fiscal nudge to make fair, efficient promotion decisions for new parents.

Administrators—university systems, school districts, hospitals—should operationalize returnships and establish predictable schedules. A paid re‑entry rotation with reduced course loads or patient panels for a defined period, paired with mentorship and skills refreshers, can transform the risk calculus for a department head managing through staff gaps. Where local childcare markets are thin, consortia can pool demand and contract slots with quality providers, securing supply for essential staff. Finance committees often balk at soft‑benefit spending; a retention‑indexed design, with funds tied to 12‑ and 24‑month stayers, converts those line items into auditable investments. The basic math—an avoidable exit costing a third of pay or more—gives administrators the language they need to defend the spend.

Policymakers should recalibrate incentives away from promotion bounties and toward retention‑indexed credits and capability vouchers. The EU's Work‑Life Balance Directive sets a floor for paternity, parental, and carers' leave and for flexible‑work requests; national transposition since 2022–2024 has advanced those rights unevenly. The next step is to tie public money to the outcome that policy can defensibly buy: parents still in their roles at 12 and 24 months post‑birth. A refundable payroll credit—modest relative to turnover costs—paid in two tranches and subject to clawbacks for early separation (outside layoffs or misconduct) would align state aims with firm incentives. Pair that with transparent promotion‑process requirements for eligibility, to remove the timing lottery that disadvantages employees around leave.

Anticipating the pushback—and the evidence that answers it

"Promotion subsidies are needed to offset statistical discrimination." Statistical discrimination is real: if women overwhelmingly request part‑time or flexible arrangements after childbirth, some firms will under‑invest in their advancement. Yet the Spanish case shows how blunt protections can produce perverse firm responses. The better route is to address the source of uncertainty managers' price: fund predictable transitions, pay for temporary backfills, and underwrite capability milestones (e.g., certifications, client handoffs, expanded spans) that transform expectations of post‑return productivity. When uncertainty falls, the incentive to under‑promote falls with it, without the signaling problem that cash‑for‑titles can create.

"Without promotion subsidies, representation in leadership won't budge fast enough." Representation matters, but paying for promotions treats the symptom, not the pipeline. The most comprehensive corporate panel we have shows the bottleneck at first promotion: the "broken rung" starves the leadership pool. Fixing process—in criteria, cadence, and documentation—raises promotions sustainably and credibly. Where public funds are warranted, target them to capability that travels across roles and employers; coaching and credentialing completed during pregnancy or in a structured returnship are investments that keep paying regardless of title. The effect is cumulative: fewer mid‑career exits, more stable experience accumulation, and a wider bench for senior roles.

"Even if imperfect, promotion subsidies raise fertility in theory—shouldn't we try?" Models clarify mechanisms, but they are not deployment blueprints. The most recent OECD and Eurostat releases underline that fertility declines are systemic, rooted in costs, timing, and social norms. Interventions that directly lower the binding constraints—affordable, reliable child care; predictable work; job security through return—have measurable, near‑term effects on both retention and family formation. The economic mass sits there: a $122‑billion annual drag in the U.S. alone from inadequate infant–toddler care. If we are going to bet scarce public funds, we should place them where the empirical payoffs are largest and fastest, not where political optics are neatest.

Building a better architecture: a practical alternative to promotion subsidies

Retention‑indexed credits. Offer a refundable payroll credit equal to, say, 15% of base pay for up to six months during a parent's return, paid in two tranches at 12 and 24 months contingent on continuous service and calibrated below average replacement costs, the credit rewards the outcome policy should value most: stability in role. Include clawbacks for early separations unrelated to layoffs or misconduct and higher credits for hard‑to‑staff roles. The structure is simple to audit and naturally discourages token promotions made only to trigger payments. (Parameters grounded in turnover‑cost ranges.)

Promotion‑neutral process mandates. Tie eligibility for credits to promotion transparency: publish criteria, include at least one structured review stage, and set calendar‑fixed windows. These process features neutralize the timing lottery that so often penalizes employees who take leave near ad‑hoc decision dates. They also improve perceived fairness among peers, which research suggests can reduce attrition risk. The mandates dovetail with the EU's Work‑Life Balance framework by translating rights into operational practice that managers can plan around.

Capability vouchers and childcare supply. Where governments want to spend directly on advancement, fund skills that travel—manager training, client‑transition workshops, technical certifications—completed during pregnancy or in a structured returnship, these investments push promotions by raising capacity, not rewarding labels. And because childcare instability is the proximate driver of absence and exit, public money buys more when it expands affordable, quality supply—especially in care deserts and for nonstandard hours—than when it chases promotion events. The quantified spillovers include fewer unplanned absences, fewer emergency exits, and smoother team operations. The $122‑billion figure is a reminder of where the economic mass truly lies.

Evaluate like we mean it. Pilot retention‑indexed credits and capability vouchers with randomized or phased rollout across sectors; pre‑register outcome measures; and publish intent‑to‑treat and treatment‑on‑the‑treated estimates for retention at 12/24 months, promotions at 36 months, and pay trajectories at 48 months. Require anonymized promotion files to be reported for audit and research. Use the Spanish natural experiment as a cautionary benchmark for firm responses, and the Child Penalty Atlas to calibrate expectations across contexts. Build the feedback loop in from day one so design can adapt before political patience runs out.

A different kind of signal

We began with stark numbers: a 1.38 fertility rate in the EU and an American fertility picture where births ticked up even as rates slid, all against a $122‑billion annual drag from inadequate child care. Confronted with that terrain, promotion subsidies look elegant in theory but brittle in practice. They purchase a label without buying what managers value: stability, predictability, and capacity. A better architecture is within reach—retention‑indexed credits, promotion‑neutral process mandates, capability vouchers, and childcare expansion that removes the binding constraint for families and firms alike. If public money is to be spent, let it buy durable productivity and family security, not a fleeting line on a résumé. The signal we should send is simple: keep new parents in their roles, grow their human capital, and let the promotions follow from the strength of their contribution, not the size of a subsidy.

The original article was authored by Olympia Bover, a Senior Research Associate at CEMF, along with four co-authors. The English version, titled "Firms, family-friendly policies, and fertility," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025, July). NCHS Data Brief No. 535: Births—Final Data for 2024.

Eurofound. (2024). Work–life balance: Policy developments.

Eurostat. (2025). Fertility statistics (Statistics Explained). https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Fertility_statistics

Gallup. (2024). Employee retention depends on getting recognition right (turnover replacement‑cost ranges).

Kleven, H., Landais, C., & Søgaard, J. E. (2024). The Child Penalty Atlas. Review of Economic Studies.

OECD. (2024). Society at a Glance 2024: Fertility.

ReadyNation (Council for a Strong America). (2023). $122 Billion: The growing, annual cost of the infant‑toddler child care crisis.

Work Institute. (2023). 2023 Retention Report (turnover cost ≈ one‑third of base pay).

LeanIn.Org & McKinsey & Company. (2024). Women in the Workplace 2024 (broken rung: 81 women per 100 men promoted to manager).

Fernández‑Kranz, D., & Rodríguez‑Planas, N. (2021). Too Family‑Friendly? The Consequences of Parent Part‑Time Working Rights (IZA Discussion Paper No. 14548).

Comment