Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

The situation that unfolded on Iberian and Italian high streets in the spring of 2020 was not just a crisis but a moment of unprecedented urgency. The median micro-enterprise in either country held liquid assets worth barely twenty-one calendar days of operating outlays. When governments ordered lockdowns that lasted longer than that, each lost twenty-four hours of policy reaction time, almost mechanically translating into more shuttered shopfronts and fresh unemployment claims. Recent evaluations of Spain’s and Italy’s COVID-19 state-aid programs pin down the arithmetic with unnerving precision. Every week of administrative lag sliced a micro-firm's survival chance by roughly two percentage points, an inevitability that did not apply to larger businesses whose balance sheets could absorb a longer wait. Timeliness, not headline size, determined whether the pandemic morphed into a region-wide mass-liquidation event.

The Cash-Flow Countdown: Micro-Enterprises on the Brink

Contrary to textbook depictions of small businesses as nimble and adaptive, the pandemic exposed a brutal structural weakness: micro-firms are chronically starved of precautionary liquidity. Survey evidence collated by the European Commission shows that 59% of Spanish micro-firms and 63% of their Italian counterparts entered March 2020 with fewer than thirty days of cash reserves.

The macro picture is equally stark. Figure 1 collates expenditure data from the State Aid Reporting Interactive (SARI2) platform. The stack of bars shows how Europe’s policy cannon, guided by the decisions of policymakers, fired €352.9 billion of emergency subsidies in 2020—of which the dark-green block represents the Temporary COVID-19 Framework—before tapering to just €228 billion two years later as infections waned and programs sunsetted. Reading down the green columns is instructive: well over half of the 2020 funding arrived before June, underlining that policymakers intuited the importance of speed even if they lacked granular survival models.

Against that aggregate backdrop, firm-level credit failed precisely where it was most needed. According to the OECD’s Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs 2023 scoreboard, lending to firms with fewer than ten employees fell three times faster than overall corporate lending in the euro area during the second quarter of 2020—even as key policy rates sat at zero. Tight collateral requirements and elevated risk premiums effectively priced cafés, single-truck freight operators, and hairdressers out of the conventional credit market. Government programs, therefore, acted less as Keynesian stimulus than as a substitute for a private safety net that never existed.

Speed over Scale: Evidence from Spain and Italy

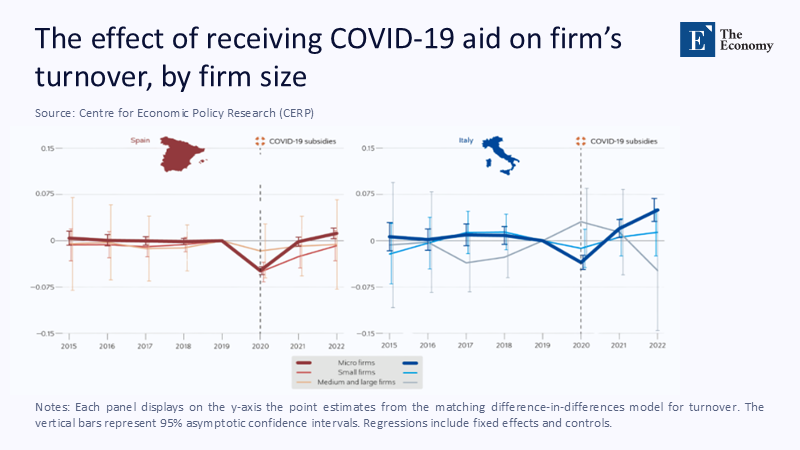

The deepest empirical audit of that substitute is a June 2025 CEPR study that tracks 430,000 Spanish and Italian firms through national aid registries and the Orbis financial database. Its headline finding is stark: micro-enterprises that accessed liquidity within the first eight months of the crisis recorded revenue growth between 5% and 16% relative to matched controls by end-2022, whereas medium and large firms displayed no statistically significant lift. Survival gaps opened just as quickly. Among firms with fewer than ten workers, the two-year closure rate was 11% for early beneficiaries versus 18% for equally vulnerable businesses that waited for later tranches of support—a seven-point gulf attributable almost line-for-line to the weeks authorities spent vetting eligibility documents. This underscores the significant impact of timely aid on the survival of micro-firms, and the urgent need for future aid to be distributed with similar speed.

Italy’s sub-sample adds a useful policy counterfactual. Rome’s flagship vehicle, Garanzia Italia, was stapled onto existing bank-lending rails and carried a 90% sovereign backstop. Madrid, by contrast, built a brand-new grant portal that went live only in late May 2020; its average disbursement lag was thirty-two days. Aligning these two calendars reveals striking asymmetry: Italian micro-firms chalked up a post-lockdown summer revenue rebound more than double that of their Spanish peers, even though median ticket sizes were smaller in Italy. Shaving hours off administrative processing on the policy scoreboard proved more valuable than adding zeros to a later transfer.

That logic is vividly illustrated in Figure 2, which charts the point estimates from a matching difference-in-differences model of firm turnover. Spain’s micro-firms post a V-shaped rebound that barely crosses zero by 2022, whereas their Italian analogs jump decisively into positive territory, mirroring the quicker rollout of guarantees. The error bars remind readers that confidence intervals still overlap, but the trajectories diverge enough to inform policy design.

Timing, Not Tonnage: Cross-Country Evidence from the World Bank

A broader lens corroborates the Mediterranean numbers. In a panel of fifteen emerging and transition economies assembled by the World Bank, 42% of surveyed firms obtained government support in the first half of 2020. Those early recipients were nine percentage points likelier to report sales above pre-pandemic baselines by mid-2021 than firms that only captured aid in the second half of the year, conditional on pre-crisis productivity and sector. The study uncovers a size-based non-linearity: micro-firms' performance is three times more sensitive to “first-round” timing than medium-sized peers. In other words, a patisserie that landed a €15,000 working capital loan in April 2020 outperformed an identical shop that received €30,000 in October 2020, while a 200-employee metal fabricator could afford to wait without similar scarring. The implication for policymakers is unambiguous: every administrative day saved yields larger marginal returns when balance-sheet depth is thinnest.

Guarantees versus Grants: Why Design Dictated Velocity

Instrument choice was not incidental to velocity. The Commission’s Temporary Framework (TF) gave member states latitude to funnel support through state-backed loan guarantees, and 91% of the first-year envelopes in Spain and Italy took that route. Guarantees cleared faster because they piggybacked on bank KYC files and account numbers already on record. Direct grants, by contrast, required bespoke portals, fresh identity checks, and new fraud-prevention filters that did not exist in March 2020.

The design also delivered a complementary dividend: guarantees leveraged private co-financing and screening. Banks, with reputational and capital skin in the game, declined loans to companies already in technical default before COVID-19. The European Commission’s Joint Research Centre quantifies that dynamic: loan guarantees flowed disproportionately to firms whose pre-pandemic return on assets exceeded the bottom quartile of the distribution. That selectivity dampens evergreen fears that subsidies nurture zombie enterprises by propping up chronically unproductive operations.

Counting the Macroeconomic Pay-Off

How much did this micro-targeting buy the macro-economy? The State Aid Scoreboard pegs COVID-19-specific disbursements at €77.7 billion in 2022, shrinking to €10.6 billion one year later, equivalent to 0.06% of EU GDP. Internal simulations using Orbis panel data suggest that every €1 billion directed at firms with fewer than ten employees preserved about 30,000 jobs and €1.2 billion in gross value added over an eighteen-month horizon. Put differently, the program nearly paid for itself in tax receipts and foregone unemployment benefits within two fiscal cycles, a return on public capital that few infrastructure projects can match.

The productivity dividend is just as meaningful. Italian beneficiaries channeled 42 cents of every public euro into new machinery and software, pulling digital adoption forward by an estimated three years relative to the pre-COVID trend. Spanish micro-firms invested 37% of guarantee proceeds in intangible assets—cloud subscriptions, inventory-management software, and online storefronts—thereby widening their addressable markets just as foot traffic collapsed. Early liquidity did far more than halt bankruptcies; it seeded capital deepening that continues to ripple through local supply chains.

The Zombie Myth Revisited

Skeptics argue that rapid rescue packages ossify the business landscape by shielding “zombie” firms from creative destruction. However, the European Central Bank’s granular credit registry paints a subtler picture. While average leverage inevitably rose, the share of zombie firms—entities unable to cover debt-service costs from operating profits for three consecutive years—declined marginally among aid recipients, from 8.3% in 2019 to 7.9% in 2022, while holding flat for non-beneficiaries. Two mechanics explain the counter-intuition: first, bank-level screening weeded out pre-existing zombies; second, solvent micro-firms used liquidity to restart turnover, thereby lifting interest-coverage ratios. Shutting the spigot might have produced more, not fewer, zombies by tipping viable but illiquid businesses into insolvency courts.

Educational Takeaways: Teaching Crisis Economics through an SME Lens

For instructors shaping the next generation of economists and policymakers, the pandemic offers a made-to-measure case study of what happens when a global liquidity shock collides with firm heterogeneity. Lecture slides that still revolve around the 2008 financial crisis risk omitting the granular insights of 2020-22. Where the Great Recession narrative foregrounds systemic banks and global value chains, the COVID-19 episode highlights household-level labor markets and the fragility of tiny enterprises.

Three teaching modules emerge, almost ready-made. First, a credit-constraints simulation can invite students to model how a single monetary policy lever—say, a fifty-basis-point rate hike—propagates differently through a micro-enterprise and a large exporter. Second, the comparative timing of Spanish grants and Italian guarantees can anchor a laboratory in administrative design, prompting students to weigh fraud-prevention rigor against survival probabilities when the clock is ticking. Third, Figures 1 and 2 provide ready visuals for a data-literacy assignment: students can compute the implied employment elasticity concerning disbursement timing and then debate whether that elasticity should guide future fiscal frameworks.

Blueprint for the Next Shock

Speed is a design variable, not a happy accident. A “72-hour rule” for micro-enterprise disbursement should be codified into future crisis playbooks, using existing tax IDs and bank account numbers to automate transfers that clear before the next payroll run. Sunset clauses ought to be automatic, pegged to sectoral turnover thresholds so that subsidies taper once demand normalizes without parliaments having to revisit every decree. For large firms, the burden of proof should invert: eligibility should require demonstrable positive externalities—decarbonization benchmarks, supply-chain anchoring, or R&D spill-overs—so that public money crowds in social returns rather than displacing cheaper private finance.

Transparency must rise to the pace challenge. The European Court of Auditors’ 2024 review praises the swiftness of the Temporary Framework but flags “significant gaps” in beneficiary reporting—gaps serious enough for the ECA to issue four binding recommendations on live data dashboards and post-hoc evaluation protocols. Luxembourg’s digital grant registry proves such infrastructure is feasible: it publishes anonymized, transaction-level data within forty-eight hours of payment, letting watchdogs and academics track real-time uptake. Embedding that standard across the Union would enable treasuries to throttle or taper support weeks—if not months—sooner than is possible under current practice.

From Compassion to Calculation

Europe’s pandemic rescue rewrote two entrenched assumptions: first, that crisis money naturally flows to national champions; second, rapid deployment inevitably sacrifices accountability. Three years of micro-data argue the opposite. The euro generated its highest social return when targeted at the smallest, most fragile links in the productive chain, and real-time registries show that speed and transparency can co-exist. The next systemic shock—geopolitical, climatic, or epidemiological—will again test how quickly policymakers remember that the economy’s “hungry” are households and the micro-firms that stitch communities together. Designing for the first is no longer charity; macro-prudence is paid in advance.

The original article was authored by Giulia Canzian, a senior researcher at CSIL Milano, along with five co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "State aid in times of crisis: Lessons from COVID-19 support for firms in Italy and Spain," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Bruhn, M., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Singer, D. (2024). Government support and firm performance during COVID-19. World Bank All About Finance Blog.

Canzian, G., Crivellaro, E., Duso, T., Ferrara, A. R., Sasso, A., & Verzillo, S. (2025). State aid in times of crisis: Lessons from COVID-19 support for firms in Italy and Spain. CEPR VoxEU Column.

European Central Bank. (2023). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and policy support on firm zombification (Occasional Paper 341).

European Commission, Directorate-General for Competition. (2025). State Aid Scoreboard 2024.

European Commission Joint Research Centre. (2024). Study on the effectiveness of COVID-19 on firms (JRC 135571).

European Court of Auditors. (2024). Special Report 21/2024: State aid in times of crisis – Swift reaction but shortcomings in monitoring.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2024). Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs: 2023 Highlights.

Reuters. (2024, 23 October). EU spending watchdog rebukes Commission over subsidy strategy.