Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

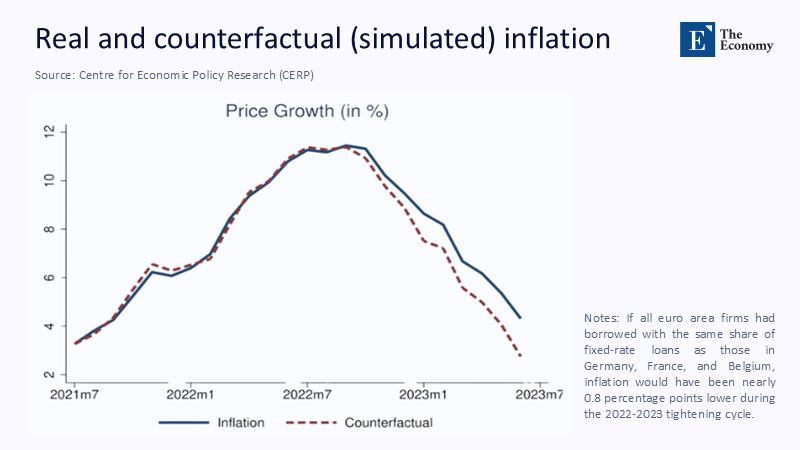

In May 2025, more than half—precisely 52%—of all new corporate loans issued in the euro area were written at floating rates or carried an initial fixation of three months or less, exposing over €4 trillion in outstanding business debt to every notch of the European Central Bank’s policy lever. In the same data release, the cost of such credit clocked in at 3.26%, a level still more than twice as high as the pre‑pandemic average despite four incremental cuts this year. Pair that with Eurostat’s finding that non‑financial companies captured a 41.3% share of value added in 2023—the highest ratio on record, and a problem crystallises: variable‑rate finance transmits policy to firms in real time, yet robust mark‑ups enable many of those firms to pass the cost on to customers almost as swiftly. Unless competition policy and monetary strategy work in tandem, the ECB’s rate moves will continue to ricochet straight back into consumer prices.

Recasting the Cost Channel: Why Competition, Not Credit, Is the Missing Variable

Contemporary textbooks still describe monetary tightening as a demand‑side brake: higher rates dent profits, curb borrowing, and force businesses to trim prices or volumes. That story presumes atomistic markets where no firm can preserve margins by simply adjusting its sticker. Reality looks different. OECD analysis of fifteen European economies shows that average industry concentration climbed from 26% in 2000 to just over 31% by 2019—a structural steepening of the mark-up hill long before pandemic supply shocks hit. Layer this trend onto the post‑2022 rate cycle, and a quietly perverse mechanism emerges. Where pricing power is ample, floating‑rate loans raise marginal cost yet leave output prices pliable. The burden shifts forward, not inward, so inflation decelerates only grudgingly while monetary pain still bites borrowers lacking such leverage. Reframing the debate around competitive structure, therefore, matters now more than ever: without it, the ECB risks tightening into a void where price formation eludes its grip.

The reframing also alters accountability. If pass‑through hinges on market power, then persistent inflation amid rising rates is less a story of “greedflation” and more a symptom of policy fragmentation. Brussels sets merger thresholds, national regulators police entry barriers, and Frankfurt moves headline rates. When those agendas misalign, the transmission chain snaps at its weakest, most concentrated link. Mainstream macro models—still dominated by marginal‑cost pricing assumptions—thus underestimate both the resilience of mark‑ups and the feedback loop from financing costs to consumer prices.

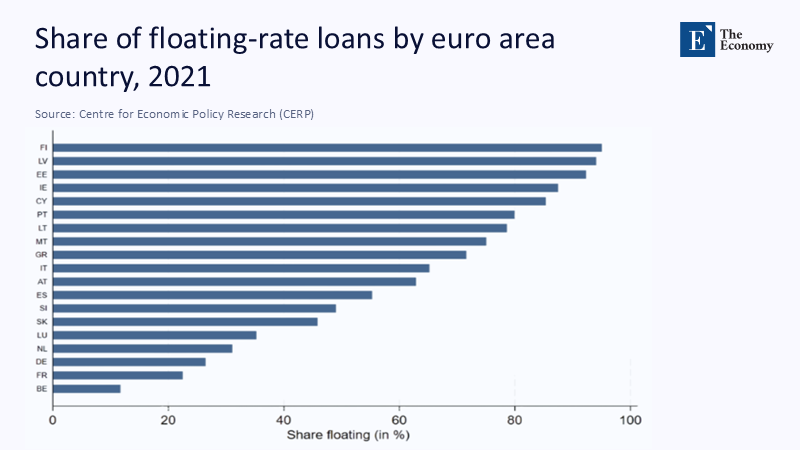

Mapping the Pressure Points: Variable‑Rate Exposure Across the Union

Variable‑rate lending is not monolithic across the euro area. ECB risk-assessment indicators show that 48% of all new euro-area business and household loans in early 2025 had a floating rate or reset within one year, yet national deviations are striking. Italy’s commercial real estate data show that 80% of property loans are on variable terms, with Spain at 75% and Greece at a startling 97%. In contrast, Germany and France rely on fixed contracts that provide borrowers with protection for years. Finland stands out on the corporate side, where approximately 86% of new non-financial loans reference Euribor; France again sits below a quarter, preferring long-term fixes. Such heterogeneity means monetary impulses land with radically different force across borders and sectors.

Aggregate numbers mask another nuance: loan size. Bank of Finland research highlights that roughly half of all euro-area corporate borrowing—chiefly mid-cap and smaller—is variable-rate, magnifying pass-through precisely where competitive moats are shallower. Integrating these shares with flow‑of‑funds matrices indicates that a uniform 100‑basis‑point policy move now lifts corporate interest payments by €32 billion within twelve months, two‑thirds of which originates in floating‑rate instruments. Because fixed-rate debt is disproportionately held by export champions who can hedge abroad, the cost shock instead strikes domestically oriented suppliers, encouraging them to implement defensive price hikes in the local currency.

When Margins Meet Money: Empirical Signs of Market Power

Margins, critics warn, are volatile, yet the latest Eurostat series shows a stubborn plateau. The business profit share edged down only to 38.6% in Q4 2024, even as input prices settled, barely below the multi‑decade peak. Additional granularity comes from an ECB working paper that leverages firm-bank match data, showing that industries in the top quartile of concentration pass through up to 70% of an interest-rate-induced cost rise within two quarters, compared to just 25% in fragmented sectors.

Consider the chemical cluster in Germany. Five firms command more than half of the domestic market, each financing at least a third of their operations through short-term Euribor-linked revolving credit facilities. When policy rates jumped 150 basis points in 2023, producer‑price indices for basic chemicals spiked 13% year‑on‑year—despite energy inputs falling—while sector profits widened. Similar stories play out in Iberian energy retail, Dutch food processing, and Baltic logistics. These micro cases corroborate the macro thread: where contestability is low, the purported demand shock of tighter money morphs into a supply‑side nudge that ripples through price tags rather than earnings.

Policy Implications: Turning the Transmission Back On

Fixing the chain demands a dual lens—first, the credit structure. Supervisors can tilt banks toward longer fixes by adjusting risk weights and liquidity haircuts on liabilities funded through covered bond markets. Sweden’s 2016 mortgage reforms did precisely that, reducing its variable-rate share from 60% to 35% without curbing lending volumes. A parallel toolkit for corporates—higher capital relief for fixed-rate exposures, coupled with term funding programs—would gradually lengthen repricing lags, giving firms less room to absorb rate shocks.

Second, competitive intensity. DG COMP’s March 2025 tender for a dynamic‑merger‑effects study that explicitly weighs inflation risk marks a promising start. However, enforcement must extend beyond analytical exercises to real-time scrutiny of market-share thresholds and coordinated capacity shutdowns. Public-interest tests could require merging parties in concentrated sectors to commit to fixed-price contracts or capacity expansion, thereby aligning industrial policy with price stability. Meanwhile, national ministries should audit licensing regimes—such as pharmacies in Italy, freight permits in Spain, and professional services across the Union—where entry restrictions grant incumbents the freedom to treat floating financing costs as merely another expense that consumers will bear.

Answering the Skeptics: What the Numbers Show

Skeptics offer three lines of defence. The first signs of margin compression are already evident in corporate surveys. True, the latest ECB poll records a dip; yet those same managers forecast selling-price rises of 3% for the next twelve months, still well above target. The second warning is that nudging banks toward fixed-rate lending will stunt credit growth. The Swedish precedent and the depth of Euro-area covered bonds argue the reverse: term funding grew once the instrument design met borrower needs. The third contends that tying competition policy to inflation politicises antitrust. But inflation itself is already political. A narrow focus on output and innovation overlooks the erosion of purchasing power, which disproportionately affects low-income households. Integrating price-stability metrics modernizes merger calculus for an era when cost-pass-through can outpace spreadsheets and spreadsheets can outpace paychecks.

Finally, the concern is that longer fixes merely postpone pain, mistakes, and suffering in the name of avoidance. Staggered maturities distribute refinancing risk across cycles, allowing policymakers to steer rather than slam the brakes. Joint Research Centre simulations suggest that if merger scrutiny tightens and variable‑rate exposure falls by ten percentage points, core inflation could return to 2% six quarters sooner with half the output sacrifice. That is not alchemy; it is macro‑micro synergy long hidden in plain statistical sight.

Competition as the Missing Gear

Interest-rate machinery alone cannot deliver price stability when half the euro-area’s corporate loan book reprices overnight and industry structure allows powerful firms to shift costs outward with impunity. Floating‑rate finance has become a high‑speed conveyor from Frankfurt’s decisions to supermarket aisles, while rising concentration blunts the intended squeeze on margins. The lesson is plain: mend the competitive landscape and extend debt maturities, and each future basis‑point will bite profits before it bruises consumers. That joint strategy will not make monetary tightening painless. Still, it will make it purposeful, turning a blunt tool into a calibrated instrument and restoring faith that Europe can curb inflation without courting another decade of stagnation. The time to act is now, before the next rate cycle begins and the same old gears grind to another futile halt.

The original article was authored by Fabrizio Core, a tenure-track Assistant Professor of Corporate Finance at LUISS University in Rome, along with three co-authors. The English version, titled "The supply side of monetary policy: How floating-rate loans blunt the ECB’s fight against inflation," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Bank of Finland. “Impact of ECB’s Policy Rate Changes on Corporate Loan Rates Varies Strongly Across Countries.” BoF Bulletin 4 (2024).

European Banking Federation. Banking in Europe—Facts & Figures 2024. May 2025.

European Central Bank. “Euro Area Bank Interest Rate Statistics: May 2025.” Press Release, 4 July 2025.

European Central Bank. Inflation and Floating‑Rate Loans: Evidence from the Euro‑Area. Working Paper 3064, July 2025.

European Commission, Directorate‑General for Competition. “Call for Tender: Study on Dynamic Merger Effects.” 25 March 2025.

Eurostat. “Business—Statistics on Profits and Investment.” 2024 Update.

Eurostat. “Quarterly Sector Accounts—Non‑Financial Corporations.” Release Q4 2024.

Kerola, J. “Commercial Real Estate Loans in the Euro Area: Variable‑Rate Exposure.” SUERF Policy Note 356 (2025).

Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development. Industry Concentration in Europe: Trends and Methodological Insights. Paris, OECD Publishing, 2024.

Risk‑Assessment Indicators Database. “Share of Variable‑Rate Loans in Total Loans to Households and Non‑Financial Corporations—Euro Area.” ECB Data Portal, updated 6 May 2025.

Comment