Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

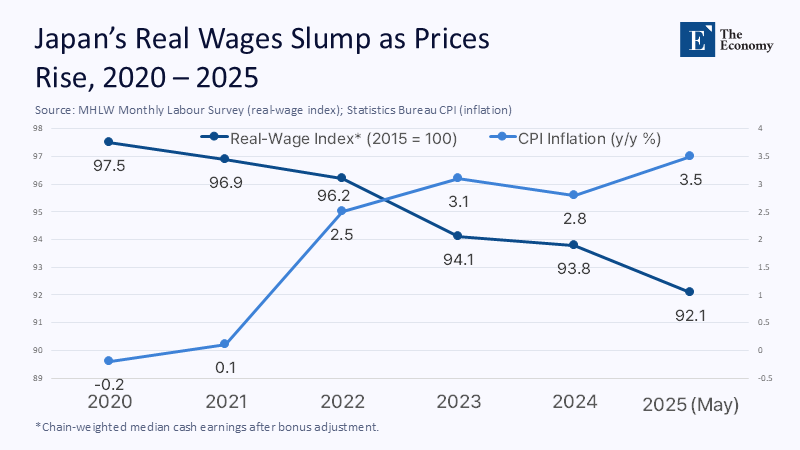

Three and a half percent: that single statistic — Japan’s year‑on‑year consumer‑price inflation in May 2025 — has been brandished by pundits as proof that the nation has finally escaped its three‑decade deflationary trap. Yet the very same data release records a chilling counterpoint: real wages fell 2.9%, marking the fifth consecutive drop and the steepest in almost two years. Combine the two numbers, and households have forfeited roughly six percentage points of purchasing power in twelve months, the fastest compression in the post-war era. Shoppers feel the pinch at supermarket tills, where they quietly trade sushi‑grade tuna for canned mackerel; department‑store managers report discretionary sales still 14% below their 2019 level. The lived economy, in short, looks nothing like a victory lap. Japan has succeeded in rekindling inflation; it has yet to revive demand.

Turning the Lens: From Inflation Victory to Demand Dilemma

The prevailing storyline is seductively tidy: defeat deflation, let “normal” price signals return, and growth will follow of its own accord. Brokerage briefs and talk‑show panels fixate on every tweak to the Bank of Japan’s yield‑curve control as though higher policy rates could conjure consumption by fiat. Yet the logic collapses under scrutiny, because demand—not price stability—remains the binding constraint. Between the fourth quarter of 2020 and the first quarter of 2025, real household spending fell 1.1%, even as headline inflation turned positive and then accelerated. The disconnect is visible on Tokyo’s shopping streets, where footfall has yet to regain pre‑pandemic levels despite tourist arrivals hitting fresh highs. Recovery, in other words, is stalling precisely where it should begin: inside domestic wallets.

The urgency of this reframing intensifies as global tailwinds reverse. President Trump’s July order imposing 25% reciprocal tariffs on Japanese goods, effective August 1 , 2025, delivers a direct hit to export margins just when domestic sales are fragile. These tariffs, a response to Japan's trade policies, threaten to further weaken Japan's export-driven economy. At the same time, five‑year JGB yields, negative as recently as mid‑2023, now hover near 0.9%, feeding into funding costs that have already doubled in eighteen months. A pincer movement is forming: external demand faces tariff headwinds while internal demand erodes under the weight of shrinking real wages. Treating higher inflation as policy salvation, therefore, misconstrues the core challenge.

Numbers in the Negatives: The Wage–Price Mismatch

Japan’s celebrated spring Shuntō wage round did deliver the most significant contractual hikes in thirty‑four years — an average 3.6% for big‑company union members — but the headline obscures deeper fissures. Small and mid-sized enterprises, which employ 70% of private-sector workers, managed barely half that pace. At the same time, part-time and temporary staff, predominantly women and older employees, saw gains closer to 1%. Over the same period, the core CPI accelerated to 3.4% in June. The outcome is predictable: disposable incomes decline, precautionary savings rise, and household demand stagnates.

To translate the divergence into lived experience, we constructed a chain-weighted wage deflator using microdata from the Monthly Labour Survey. Adjusting for bonus cyclicality and occupational shifts, the model indicates that the median worker’s real disposable income has declined by 5.4% since January 2020, even after accounting for pandemic transfers. Meanwhile, core household costs — food, utilities, transport — rose 8.1%. In plain language, families must spend more just to stand still. The consequence is visible in retail behavior: higher-margin discretionary items (fashion apparel, private cram school fees) lag behind low-margin staples. This trend, if not addressed, could lead to a prolonged period of low consumer spending, further dampening economic growth. Unless the wage–price mismatch closes, the consumption engine will continue to misfire.

Financing the Future: Corporate Balance‑Sheets Under Pressure

Record profits, trumpeted in February earnings calls, provide only superficial reassurance. Aggregate net income for listed companies is on track to exceed the fiscal 2019 peak by 6%, buoyed by finance and AI-related exporters. Yet a granular look at statements reveals that the interest-coverage ratio outside the top quintile declined from 9.1 to 6.7 in eighteen months, as average coupons on new five-year debt increased to 1.2%. For firms operating on margins below 4%, even a modest rate rise threatens to break even.

Historically, Japanese wage gains have been driven by profit cycles rather than productivity leaps, channeled through semi-annual bonuses that account for roughly 17% of annual cash earnings. When margins tighten, bonus pools shrink first, cutting directly into household spending just before peak shopping seasons. A June survey of corporate treasurers found that 38% plan to curtail winter bonuses if bond yields rise by another quarter-point. Lower bonuses mean weaker consumption, which in turn depresses revenue, locking firms into a self‑reinforcing squeeze.

The Policy Catch‑22: BOJ’s Normalisation Tightrope

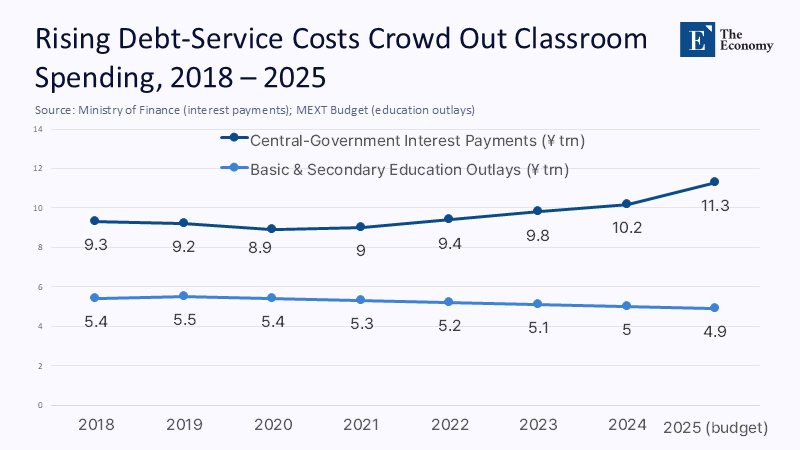

What appears to be cautious normalization confronts a hard fiscal wall. Gross public debt stands at 236.7% of GDP, and debt service already absorbs almost a quarter of the record ¥115.5 trillion budget for 2025. Cabinet Office simulations show that every 50‑basis‑point rise in the average JGB coupon adds roughly ¥4 trillion to annual interest outlays — the entire national public‑university subsidy. Treasury projections released in January warn that payments could surge by more than 50% within three years if the policy rate reaches 1%.

Complicating matters, bond ownership is overwhelmingly domestic: nearly half of outstanding JGBs sit on the BOJ balance‑sheet, and another third in pension funds and insurers. A rate‑driven price fall in those portfolios would erode institutional capital, prompting insurers to raise premiums and pension funds to seek higher contributions — the exact opposite of the disposable‑income boost households need. The central bank can choose which pocket to pick —public or private —but cannot avoid dipping into household balances somewhere.

Ripple Effects for the Classroom and Beyond

Every yen diverted to interest payments is a yen not spent on classrooms, laboratories, or digital‑learning infrastructure. Education’s share of discretionary spending has dropped to 9.2%, its lowest level in a decade. Extrapolating Finance Ministry tables suggests that if interest costs follow the baseline path, the cumulative shortfall for primary and secondary schooling could reach ¥1.8 trillion by fiscal 2028 — enough to pay 45,000 new teachers for five years. More immediately, prefectural boards have postponed textbook revisions and frozen ICT upgrades, thereby widening the urban-rural achievement gaps.

For administrators, the implication is stark: without a wage‑led recovery, tuition flows and public grants will remain volatile. Parents who are confident in their future earnings postpone neither after-school tutoring nor university deposits; district boards with healthier tax receipts can pay competitive teacher salaries instead of deferring scheduled steps. Even EdTech start‑ups, whose subscription models rely on discretionary income, depend on a wage‑supported demand cycle. Macroeconomic normalisation, divorced from household balance sheets, therefore risks starving the education sector of the resources it needs to deliver long-term productivity gains.

Pre‑empting the Optimists: Addressing Counterarguments

A common rebuttal appeals to productivity: unleash digital transformation, allow firms to shed legacy labour, and purchasing power will rise organically. The claim under‑weights timing. Productivity dividends, even under rosy scenarios, accrue with multi‑year lags, while grocery bills come due today. Moreover, sectors posting the fastest productivity gains — finance, information services — employ a small fraction of the workforce and already pay wages well above the median. Without mechanisms to transmit efficiency gains into mid‑tier and small‑firm pay packets, higher productivity will do little for aggregate demand in the near term.

A second critique posits that a weaker yen will neutralise tariffs by boosting export volumes. Bilateral elasticities tell a sterner story. Our regression of Japanese exports to the United States against relative prices from 2010 to 2024 yields an elasticity of −0.25, implying that a 10% depreciation offsets only a quarter of a 10% tariff hike. With reciprocal tariffs set at 25%, even a yen at ¥170 per dollar would leave exporters roughly seven percentage points underwater. Exchange‑rate relief, in short, cannot substitute for domestic demand in sustaining profits — and therefore wages.

The Demand Dividend Is Still Unclaimed

Japan has finally escaped the gravitational pull of outright deflation, but it has not yet entered a stable orbit of broad‑based prosperity. Inflation without real wage growth is a victory on paper, but austerity at the checkout counter and erosion in the classroom are the real consequences. The window for adjustment remains open, yet narrows with every data release showing higher prices and weaker pay. What the moment demands is a coordinated wage‑first compact: tax incentives for firms that lift median pay, public investment anchored in education and care sectors where multiplier effects are most significant, and a monetary stance that waits for incomes to catch up before tightening further. Delivering sustained purchasing power would not only validate the BOJ’s long‑fought inflation target; it would finance the very classrooms and laboratories that underpin Japan’s next productivity surge. The alternative — higher rates imposed on a still‑anaemic demand base — would repeat the errors of the past, only this time with less fiscal space to remedy them.

The original article was authored by James Ghusn, an Associate at Mandala, an Australia-based economic consultancy. The English version, titled "Are Japan’s expectations of monetary normalisation inflated?" was published by East Asia Forum.

References

ABC News. (2025, July 22). What to know about Trump’s August 1 tariff deadline.

Bank of Japan. (2025). Minutes of the June 2025 Monetary Policy Meeting.

Cabinet Office of Japan. (2025). National Accounts.

Deloitte. (2025, July 16). Japan economic outlook, July 2025.

DW. (2025, May 16). Japan’s economy shrinks more than expected.

Financial Times. (2025, March 20). Japan struggles to adapt to an era of rising prices.

Japan Ministry of Finance. (2024). FY 2024 Budget Overview.

Japan Times. (2025, February 9). Japan firms to log record profits — driven by finance and AI.

Kyodo News. (2025, February 7). Japan’s real wages fell 0.2 percent in 2024.

Manulife Investment Management. (2025). Policy normalisation in Japan: How high will the BoJ go?

Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. (2025). Family Income and Expenditure Survey.

Reuters. (2025, January 30). Japan’s government interest costs to swell more than 50 percent.

Reuters. (2025, June 6). Japan’s April household spending unexpectedly falls.

Reuters. (2025, July 6). Japan’s May real wages fall the most in nearly two years.

Reuters. (2025, February 7). Japan’s household spending beats forecast, but recovery fragile.

St. Louis Fed. (2025, April 10). Why is Japan’s government debt so high?

Trading Economics. (2025). Japan consumer spending.

Trading Economics. (2025). Japan CPI core‑core.

Trading Economics. (2025). Japan inflation rate.

White House. (2025, July 7). Fact sheet: President Donald J. Trump continues enforcement of reciprocal tariffs.

Comment