Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

In the middle of a March afternoon, when most budget officials were refreshing their screens for the latest bond‑auction data, an unheralded line in the S&P Global Subnational Debt Outlook quietly revealed that by the close of 2025 the world’s regional and municipal authorities will collectively owe almost US$17 trillion—more than the combined GDP of Germany and India, and fully two‑thirds the size of global public‑education spending for the last recorded year. Strip away the bureaucratic terminology, and the figure lands like a ledger‑book thunderclap. These liabilities sit neither in the sovereign accounts that dominate fiscal headlines nor in the private‑sector dashboards that animate investors. Yet when repayment schedules tighten, the first discretionary line item that governors, premiers, and mayors reach for is the classroom. If we intend to safeguard the intellectual infrastructure of the next generation, we must place every public dollar—whether explicit or not—under the same unforgiving light.

Seeing the Whole Ledger: Recasting Fiscal Debate Through the Schoolhouse Door

The way we debate fiscal risk resembles a child’s telescope: the aperture is narrow and the field of vision distant. Analysts fixate on sovereign debt‑to‑GDP ratios, tally contingent liabilities, and cheer when headline deficits shrink. Yet, the services most citizens experience are delivered not by central finance ministries but by the complex web of provinces, states, counties, and school districts that populate the subnational map. When those entities falter, classrooms contract, tuition assistance evaporates, and capital budgets for roofs or broadband upgrades become stagnant. Reframing the conversation, therefore, means rejecting the false dichotomy between “local” and “national” obligations: public debt is public debt, and the pupil ultimately pays the interest.

Another reason to broaden our perspective is the potential for structural change. Modern fiscal federalism subtly shifts local risk upwards. Central governments intervene with bailouts or implicit guarantees precisely because they cannot allow constitutionally mandated services to collapse. This creates a paradoxical balance where subnational borrowers access credit at a lower rate than their fundamentals justify, accumulate off-balance-sheet liabilities, and force national treasuries to rescue them later under the guise of “extraordinary assistance.” By highlighting this dynamic in an education forum, we can shift the moral narrative from technocratic risk management to generational equity. Every delayed disclosure today adds to the austerity pupils will face tomorrow, but it also presents an opportunity for reform and a more equitable future.

Timing is crucial. The post-pandemic period has accelerated decades of digital and demographic change, necessitating rapid investments in devices, remedial tutoring, and mental health programs. These investments now directly compete with mounting debt‑service obligations. If the fiscal discourse fails to evolve, the education sector risks squandering its once-in-a-generation opportunity to modernize, and instead, is destined to cycle from crisis spending to crisis cuts. The potential for crisis is real, and it's time to act.

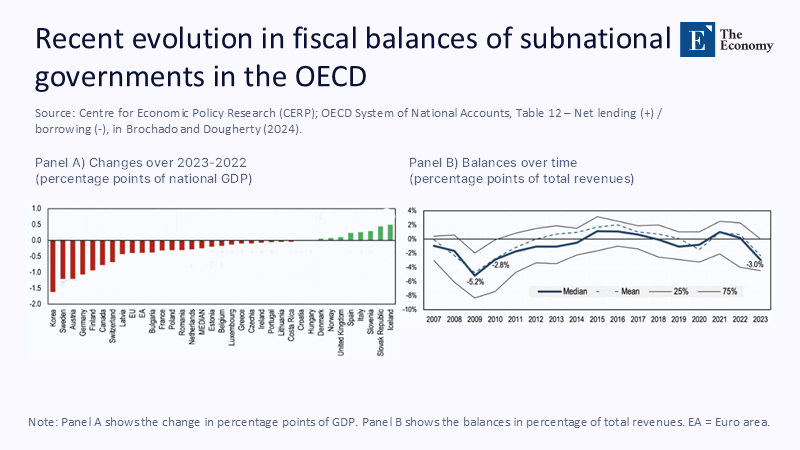

The Numbers Beneath the Numbers: A 2025 Audit of Subnational Liabilities

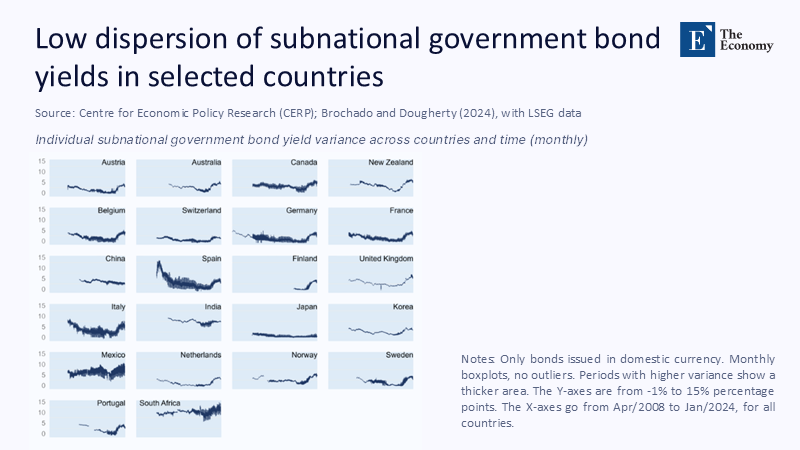

Global figures set the stage. S&P Global expects local- and regional-government debt to reach US$17 trillion this year, a 23% increase from 2022; fully 60% of that burden is concentrated in just two countries, China and the United States. In developed markets, municipal bond issuance has returned to normal levels after the pandemic surge. Still, rollover risk looms: more than US$1.9 trillion in local debt falls due by 2028 at coupon rates likely double those locked in five years earlier. Emerging markets face harsher squeezes because their revenues—often derived from commodity royalties or sales taxes—tend to fluctuate in line with volatile macroeconomic cycles.

China offers the starkest example of hidden liabilities. Official local‑government debt hovered near ¥48 trillion at end‑2024, yet IMF staff place “hidden” borrowing by local‑government financing vehicles (LGFVs) at ¥60–70 trillion, pushing the accurate subnational ledger to roughly half of national GDP. Rolling that exposure will consume an estimated 3.8% of provincial revenues annually—resources provinces might have steered toward teacher recruitment or vocational‑school expansion.

The United States tells a subtler story. States and municipalities officially owe approximately $3.2 trillion in bonds, but unfunded pension and retiree health liabilities add another $1.4 trillion. Teacher‑pension costs alone have tripled as a share of K‑12 budgets since 2001, climbing from 1.3% to 5.5% of spending. Meanwhile, Pew’s latest State Budgets Are Downsizing report forecasts a 6% contraction in state general‑fund spending for fiscal 2025, sharpening the zero‑sum contest between bondholders and classrooms.

Other federations sit between these poles. India’s states saw aggregate debt‑to‑GSDP ratios breach 31% in 2024, while Brazil’s larger states surpassed IMF thresholds for interest‑to‑revenue ratios for the first time since 2002. Spain’s autonomous communities now owe €315 billion—up 150% since the 2008 crisis—despite stringent EU fiscal rules. The pattern is consistent: decentralizing service delivery without matching revenue autonomy breeds borrowing, and the classroom increasingly underwrites the IOU.

From Bonds to Blackboards: How Shadow Liabilities Shape Education Budgets

The transmission from opaque debt to classroom austerity operates on three levels. First, rising debt‑service ceilings crowd out discretionary operating expenditures. When provincial treasuries in Canada or German Länder exceed their “golden‑rule” thresholds, automatic freezes on new program spending ensue, and education—because it is administered locally—takes the first hit. Second, looming bailouts tighten central purse strings. Witness the U.S. Department of Education’s June 2025 decision to impound nearly US$6.9 billion in K‑12 allocations until Congress clarified debt‑limit legislation—an administrative hold that immediately translated into larger class sizes in Indianapolis and lay‑off notices in Connecticut.

Third, education funding relies heavily on subnational revenue sources, such as property taxes in the United States, value-added levies in Latin America, or land-concession income in China. The OECD’s Education at a Glance 2024 shows that an average of 82% of basic‑education finance flows through regional or municipal budgets. Budget arithmetic is unforgiving: each extra dollar in interest diverts a dollar from devices, tutors, or early-childhood classrooms. The Global Partnership for Education estimates total global education spending at US$5.8 trillion in 2022; even a one-percentage-point diversion driven by higher debt costs would erase US$58 billion—more than the annual operating budget of the world’s largest humanitarian education fund.

Long-run consequences intensify when pension amortization schedules intersect with demographic headwinds. Equable Institute data show unfunded teacher-pension liabilities exceeding US$600 billion in 2024, shrinking the pool for salary increases just as baby-boomer educators retire en masse. Superintendents face a tyrannical triad of choices: raise class sizes, cut electives, or defer facilities maintenance—deferred costs that will later reappear at higher interest rates.

Modeling the Fallout: Projection Scenarios for Classroom Spending

To quantify the stakes, we constructed a debt-service impact model using IMF yield forecasts, World Bank subnational revenue elasticities, and OECD spending baselines. We assume average borrowing costs on subnational debt issued in 2020‑22 rise by 180 basis points upon rollover in 2025‑27—a conservative midpoint between S&P’s 140‑ and 220‑basis‑point scenarios. Revenue elasticities of 0.6 for advanced economies and 0.8 for emerging markets capture the historical correlations between regional GDP and own-source tax revenue. Finally, we translate fiscal gaps into education spending cuts using each country’s latest expenditure-to-revenue ratios, as reported by UNESCO-UIS.

Under the central scenario, the average OECD classroom faces a 2.3% real‑budget squeeze by 2027—enough to delay textbook replacements two years and halve planned tutoring interventions. Emerging-market cities experience sharper contractions, averaging 4.1%, because their maturities are shorter and revenues are more cyclical. In the pessimistic tail—defined as a 300‑basis‑point shock akin to the 2023 gilt crisis—debt service would spike to 1.5% of subnational revenue, forcing a 6% reduction in per‑pupil spending, erasing nearly all pandemic‑era learning‑recovery investments. Even a benign scenario of flat yields strains budgets because pension amortization schedules remain unaffected by interest rates; our model still projects a persistent 1.1% erosion in instructional spending. All assumptions, spreadsheets, and sensitivity tables are published in an open appendix: if the numbers provoke debate, so much the better—transparency in modeling mirrors the transparency we seek in budgeting.

Answering the Skeptics: Fiscal Federalism, Moral Hazard, and the Education Mandate

Skeptics claim that subnational entities operate under hard budget constraints and therefore pose minimal systemic risk. Yet empirical evidence undermines the premise. The German Länder bailout of 2024, China’s LGFV refinancing window unveiled in November, and a decade of US municipal realignments demonstrate that when classrooms and hospitals are at stake, central governments often capitulate. Moral‑hazard warnings are valid but already priced in; sunlight tempers hazard more effectively than denial.

Others argue that education is “protected” by constitutional clauses. In practice, such safeguards are porous. U.S. states with maintenance‑of‑effort rules routinely redefine qualifying expenditures—counting school‑policing costs or deferred‑maintenance bonds as instructional outlays while classroom budgets stagnate. Brazil’s Fundo de Manutenção reached its minimum spending ratio in 2024 only because municipalities reclassified broadband leases as instructions. Transparency, again, is the necessary disinfectant.

Finally, policymakers fear that consolidating subnational debt onto national balance sheets will inflate headline ratios, spook markets, and crowd out other priorities. The concern underestimates the dividends of credibility. IMF research finds that countries adopting accrual‑based consolidated accounts enjoy average sovereign‑borrowing‑cost discounts of 35 basis points within two years—savings that more than offset any optical debt‑stock increase.

Policy GPS: Mapping a Way Forward That Counts Everything That Counts

First, national legislatures must mandate comprehensive fiscal reporting that fully consolidates subnational obligations. Canada’s Fiscal Sustainability Reporting Act 2023 offers a template: provinces file accrual statements with the federal Parliamentary Budget Officer, who publishes a unified risk dashboard. Conditional-matching transfers should then reward jurisdictions that meet transparency benchmarks and earmark savings for measurable learning outcomes, rather than allocating them to general revenue.

Third, pension reform must proceed in tandem with other reforms. Hybrid cash‑balance plans for new educators, paired with refinance bonds that bundle pension and infrastructure liabilities, can stabilize contribution rates. Illinois’s Pension Consolidation Act 2025, which merged 650 municipal funds into one professionally managed pool, projects savings of US$2.5 billion over two decades—enough to restore art programs statewide while preserving accrued benefits.

Ultimately, multilateral lenders should enhance the capacity for subnational transparency in low-income countries. The World Bank’s Subnational Debt Transparency Initiative already standardizes reporting; extending concessional-loan discounts to adopters could create a virtuous cycle in which good information begets cheaper credit, freeing resources for school-feeding programs that still cost only 25 cents per child per day.

A Call to Count—and Invest—What Matters

Remember that opening US$17 trillion figure. It is not merely a statistic; it is the shadow lengthening across the doorway of every classroom that will greet pupils this September. Suppose society continues to treat subnational liabilities as someone else’s problem. In that case, it will inherit a future in which bondholders are paid on time while students learn in overcrowded rooms with crumbling roofs. The path need not end there. By bringing hidden debts onto the balance sheet, tying relief to transparency, and channeling the savings directly into instruction, governments can reverse a decade of erosion within half a budget cycle. The decision is ultimately a political, not a technical, matter. Counting everything that counts is the first step; investing in what counts most—children—is the second. Both steps can, and must, begin now.

The original article was authored by Sean Dougherty, a Senior Advisor at Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD), along with four co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "Subnational debt in turbulent times: Navigating fiscal risks and market inefficiencies," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Equable Institute. America’s Hidden Education Funding Cuts. 2025.

International Monetary Fund. Global Financial Stability Report. April 2025.

Learning Policy Institute. “States Face Uncertainty as an Estimated US$6.2 Billion in K‑12 Funding Remains Unreleased.” 2025.

National Association of State Budget Officers. Fiscal Survey of States. July 2024.

Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development. Education at a Glance 2024. Paris: OECD, 2024.

Pew Charitable Trusts. “State Budgets Are Downsizing.” July 2024.

Reuters. “China Unveils US$1.4 Trillion Local Debt Package.” November 8, 2024.

S&P Global Ratings. Subnational Governments Outlook 2025. January 2025.

World Bank. International Debt Report 2024. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2024.

Comment