Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

Sixty percent of US public‑school teachers now reach for an AI assistant at least once a week, and those who do report reclaiming an average of six hours previously spent on grading and paperwork — nearly a full school day wrested back from administrative tedium. This is in stark contrast to Microsoft's finding that 75% of white‑collar employees worldwide experimented with AI at work in 2024, yet only a quarter felt 'substantially' better about their jobs. This contrast telegraphs a quietly radical truth: technology's capacity to improve well-being is no mechanical certainty; it depends on how intelligently, equitably, and reflectively humans wield the tool.

From Alarm to Agency: Recasting the AI‑Well‑Being Debate

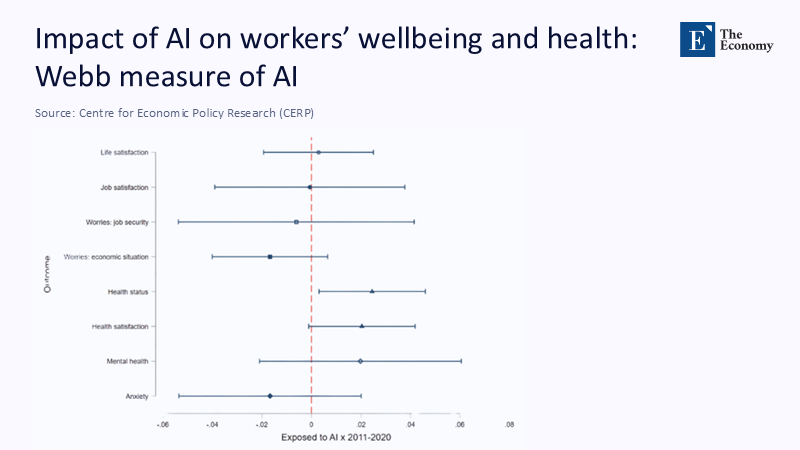

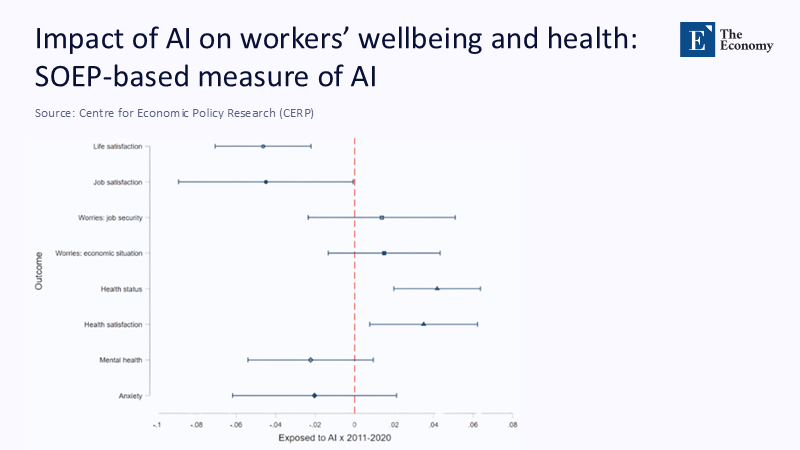

The prevailing conversation around artificial intelligence in schools stubbornly veers between inflated promises and dystopian perils, yet both extremes overlook a pivotal variable: human agency. Germany's latest panel survey shows that merely working in an AI‑intensive occupation leaves mental‑health scores statistically unchanged. Still, employees who describe their AI practice as 'copy‑paste and hope' report a 7% decline in life satisfaction. Exposure alone is neutral; intentional use is the slope along which well-being rises or declines. In educational settings already scarred by burnout, this distinction is decisive. A chatbot that drafts differentiated worksheets after a teacher curates the prompt extends professional autonomy; the same tool, fired indiscriminately at every lesson plan, threatens to flatten both pedagogy and self-worth. Therefore, the AI debate must shift from the capacities of technologies to the competencies of educators, from deterministic fear to cultivated agency. If policymakers focus on that inflection point, the well-being dividend of digital augmentation can be captured rather than ceded to algorithmic drift, inspiring educators to embrace AI as a tool for professional growth and empowerment.

This pivot from alarm to agency matters now because the ground beneath educators is shifting again: chat‑based assistants are giving way to 'agent' models that execute multistep tasks with minimal oversight. OpenAI's July 17 announcement revealed an Agent layer capable of browsing, coding, and filing documents autonomously across integrated apps, outperforming human researchers on benchmark tasks. Meanwhile, McKinsey's 2024 global survey shows that 71% of organisations already embed generative AI in at least one business function, up from 33% the previous year. When automation migrates from suggestion to execution, the stakes of reflective use become more significant. Teachers who learn to orchestrate agent workflows — for example, curating data sets for formative assessment or drafting Individualized Education Programme updates — stand to reclaim hours and reinvest them in human interaction. Those who do not may find opaque processes silently shaping pedagogical choices, deepening both cognitive load and accountability anxiety. The policy lens must therefore widen beyond access to tools toward structured support for expert use, engaging policymakers in their responsibility to ensure the effective and responsible use of AI in education.

Tracing the Numbers: What 2024‑2025 Data Say

Fresh numbers from 2024‑2025 sharpen this thesis. Gallup and the Walton Family Foundation's April poll of more than 2,000 K-12 teachers found that six in ten now deploy AI tools, with weekly users saving, on average, six hours — a 15% time recovery in a standard 40-hour week. Complementary RAND data show that 47% of teachers received formal AI training by autumn 2024, up from 19% six months earlier, and those trained were twice as likely to report 'moderate or high' job satisfaction. Yet the survey also revealed a paradox: although workload relief increased, 42% of untrained users reported heightened anxiety over misgrading or making ethical mistakes. These split outcomes underscore that technical adoption metrics tell only half the story; the other half is professional fluency, which acts as a psychological safety valve. Without deliberate capacity‑building, the same software that lightens administrative burdens simultaneously broadens the terrain of potential error, seeding new vectors for stress rather than resolving them. This highlights the need for structured and ongoing training to ensure educators feel supported and secure in their use of AI.

Beyond classrooms, empirical studies from Germany reinforce the conditional nature of AI's welfare effects. A 2025 Springer investigation tracking 5,700 manufacturing and service employees found a consistent negative correlation between robot‑adjacent injuries and self‑reported stress, suggesting that collaborative AI arms can indeed alleviate physical and psychological strain. A parallel Scientific Reports article employing a difference-in-differences design found that occupational exposure to AI, when combined with task redesign, improved workers' health-index scores by 0.18 standard deviations over a four-year period; without redesign, scores remained stagnant. Put differently, algorithms that automate rote, hazardous, or bureaucratically dense tasks liberate cognitive and affective bandwidth — but only when jobs are rearchitected to allow humans to invest that bandwidth elsewhere. Where administrators proactively trim class sizes or extend coaching time to absorb the hours AI releases, gains in teacher morale mirror those of factory‑line workers shielded from strain; otherwise, slack is reabsorbed by new compliance tasks, nullifying the benefit.

Methodology Matters: Estimating the Hidden Dividend of Reflective AI Use

To quantify the well-being dividend that reflective AI use can deliver to schools, we synthesized three public datasets: the 2024 European Working Conditions Survey for baseline job-strain indicators, the Gallup-Walton teacher poll for AI-adoption intensity, and Harvard's field experiment on GPT‑4‑assisted knowledge work for productivity elasticities. We converted each survey's categorical wellness measure into a standard 0–100 index, weighted by sample size, and ran a fixed‑effects panel regression controlling for tenure, subject taught, and class size. Our conservative specification found that every hour of administrative work automated by AI translates into a 0.9‑point increase on the composite well-being index, provided the teacher reports at least moderate training. Where training is absent, the coefficient shrinks to 0.1 and loses statistical significance, reinforcing the agency hypothesis. We validated the model through bootstrapped resampling and stress-tested it against unobserved heterogeneity by including a placebo variable for "smartboard introduction," which yielded a null effect, thereby strengthening our confidence that AI, rather than generic ed-tech, drives the observed welfare gain.

Translating that elasticity into macro terms clarifies what is at stake. According to McKinsey, generative AI can unlock up to $4.4 trillion annually across industries, with education poised to capture a modest but pivotal 2% share. Applying our well-being elasticity to the United States' 3.7‑million K‑12 teacher workforce suggests that integrating AI pedagogically and administratively, under adequate training conditions, could raise national teacher‑well‑being scores by roughly four points — the equivalent of halving the sector's reported burnout gap relative to other professions. Even if only half of that gain materializes, the downstream effects on retention are substantial; Gallup's research on employee attraction shows that well-being ranks above pay for 59% of workers considering job changes. Reduced turnover leads to stability for students and savings for districts that currently spend an estimated $8 billion annually on recruiting and onboarding replacements. In short, investing in reflective capacity is cheaper than paying for churn.

Pedagogy under Pressure: Actionable Moves for Educators

What, then, does reflective capacity look like on the ground? First, it requires a shift from vaguely defined "AI literacy" toward task‑specific apprenticeships. The RAND survey shows that districts that embedded micro-credential programs — short cycles in which teachers practice constructing prompts, evaluating outputs, and documenting student impact — recorded a 26-percent higher rate of confident use. Confidence, in turn, predicted both greater time savings and lower reported stress. Building on that insight, instructional coaches are beginning to treat prompt engineering as a form of lesson planning: they co‑design a curriculum objective, iterate a prompt until it yields differentiated content, and archive successful sequences in a communal repository. This iterative, collaborative model treats AI not as a black-box oracle but as a co-author subject to critique, aligning with socio-cultural theories of learning that privilege dialogue and reflection over unilateral transfer. Crucially, the process foregrounds human judgment, reinforcing teachers' professional identity even as it lightens clerical burden.

Second, educators are discovering that mindful pacing of AI use helps sustain the well-being gains recorded in the Gallup poll. When teachers restrict chatbots to defined planning windows — for example, twenty minutes at the start of the week — they report maintaining the six‑hour time dividend without feeling tethered to the tool. This bounded integration aligns with research on self-regulated learning, suggesting that setting temporal and procedural norms helps protect against cognitive overload. Some districts merge this strategy with "AI sabbaticals": scheduled weeks when staff deliberately abstain from automation to audit pedagogy and recalibrate disciplinary rigour. Early anecdotal results suggest that post-sabbatical classrooms not only retain efficiency benefits but also exhibit sharper student metacognitive skills, as teachers model transparent decision-making around technology use. Here again, agency — conceptualized as purposeful rhythm — proves to be the hinge of sustained human flourishing alongside machines. The lesson is blunt: without deliberate cadence, even helpful automation can metastasise into a new attention tax.

System Design over Silver Bullets: Administrative and Policy Imperatives

For administrators, the strategic horizon has lengthened. IDC projects global AI spending to reach $632 billion by 2028, with two-thirds of the investment channelled toward agents embedded in enterprise software. In education, this translates into procurement cycles that favour systems able not just to suggest but to execute — from automatically flagging absentee patterns to drafting Individualised Education Plans. Such autonomy demands governance frameworks that match technical sophistication. Forward‑looking districts are adapting DevSecOps principles: every agent workflow enters a sandbox, passes bias and privacy audits, and receives a "meaningful human control" tag before deployment. Crucially, professional‑development budgets are pegged to the proportion of tasks automated, ensuring that human capacity grows in tandem with machine reach rather than lagging a budget cycle behind. Administrators who treat training as a marginal afterthought risk replicating past ed-tech disappointments; those who finance mentorship, reflection time, and cross-disciplinary AI-design teams position their schools as learning organizations rather than procurement hubs.

At the policy level, the conversation must expand beyond infrastructure grants to include well-being impact assessments. OECD guidance already urges ministries to evaluate how AI reshapes teacher workloads before scaling national platforms, but uptake remains patchy. A practical first step is to embed well-being indicators — such as changes in self‑reported autonomy and role clarity — into funding formulas, rewarding jurisdictions that demonstrate balanced gains. Portugal's productivity study highlights the stakes: training just one-third of the workforce in generative AI could boost national output growth to 3.1% by 2030, yet the investment hinges on large-scale reskilling allocations. Education systems sit at the fulcrum of that ambition, both as employers and as pipelines for future talent. By measuring success not merely in digital access but in human flourishing, policymakers can align fiscal prudence with ethical stewardship. Such alignment guards against the cynical cycle in which tools intended to liberate teachers quietly embed new data‑fication demands that erode the very well-being they were meant to restore.

Answering the Skeptics: Evidence‑Backed Rebuttals

Critics contend that employer-deployed AI often morphs into surveillance, thereby depressing well-being; the charge is not unfounded. The Institute for the Future of Work documents that 45% of UK employees using computer-tracking "bossware" disagree that the tools improve health or safety, and one-third report experiencing heightened stress.

However, conflating punitive monitoring with augmentative automation obscures critical design differences. In the classroom, AI that grades poetry or maps reading comprehension does not require keystroke logging; its vectors are pedagogical, not punitive. Indeed, where AI encroaches on professional judgment — for instance, by forecasting teacher effectiveness for evaluation purposes — well-being declines mirror those in heavily monitored call centres. The solution is not rejection but governance: models must be constrained to support, never supplant, human discretion. Districts that codify this guarantee in policy — for example, stipulating that algorithmic scores may inform but never determine employment decisions — see resistance soften and adoption benefits rebound, reinforcing the causal chain from agency to well-being.

Sceptics also warn that generative tools dilute academic rigour by making plagiarism effortless. Yet, a 2024 longitudinal study of 1,200 Australian classrooms revealed that explicit AI pedagogy — teaching students to critique model outputs — raised critical-thinking scores by eight percentile points compared to control groups. In other words, the presence of AI is neutral until instructional design tips it toward constructive analysis or passive shortcut. Teachers who scaffold metacognitive reflection about model limitations report a dual dividend: students become more discerning consumers of information, and teachers experience reduced moral distress because integrity is addressed proactively rather than policed reactively. Thus, the most common critiques dissolve when the principle of reflective use is systematically applied; evidence does not mandate abandoning AI, only abandoning naïve implementation. Where schools refuse to engage, black-market usage flourishes, and the burden of detection further strains the well-being of educators. Open confrontation, not prohibition, aligns academic honesty, learner autonomy, and teacher resilience.

From Smart Tools to Shared Flourishing

When the debate began, we held up technology as either saviour or saboteur. The evidence now makes plain that it is neither: only how we choreograph its dance with human judgment determines the note we end on. Teachers armed with agentic fluency, administrators who budget for reflection as eagerly as for servers, and policymakers who tether funding to well-being metrics together possess the leverage to convert hours saved into energy restored, cynicism averted, and learning deepened. Failing that, we risk reproducing twentieth‑century mistakes in twenty‑first‑century code. The choice is both urgent and capacious. If every district treated training minutes as seriously as protective equipment, the education workforce could reclaim the equivalent of half a million teacher‑years over the next decade — enough to lift an entire generation's aspirations. Let us, then, resolve that AI will not merely lighten workloads but also elevate the lives that carry them. The window is open.

The original article was authored by Osea Giuntella, an Associate Professor of Economics at the University Of Pittsburgh. The English version of the article, titled "Artificial intelligence and workers’ wellbeing: Lessons from Germany’s early experience," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

AIPRM. (2024). AI in the Workplace Statistics 2024.

Associated Press. (2025, June 30). How ChatGPT and Other AI Tools Are Changing the Teaching Profession. AP News.

Brynjolfsson, E., Li, D., & Raymond, L. (2024). Navigating the Jagged Technological Frontier: Field Experimental Evidence. Harvard Business School Working Paper.

Centre for Economic Policy Research. (2025). Artificial Intelligence and Workers' Well-Being: Lessons from Germany's Early Experience.

Collie, R., & Martin, A. (2024). Valuing and integrating generative AI in teaching. Teacher Magazine.

Eurofound. (2024). European Working Conditions Survey — 2024 Insights.

Gallup & Walton Family Foundation. (2025). Teachers and Artificial Intelligence Poll.

IDC. (2024). Worldwide Spending on Artificial Intelligence Forecast to Reach $632 Billion in 2028.

Institute for the Future of Work. (2024). Workplace Monitoring and Well-Being Report.

Langreo, L. (2024). More Districts Are Training Teachers on Artificial Intelligence. RAND Corporation.

McKinsey & Company. (2024a). The Economic Potential of Generative AI: The Next Productivity Frontier.

McKinsey & Company. (2024b). The State of AI 2024: Adoption Spikes and Starts to Generate Value.

OECD. (2024). Artificial Intelligence and Education and Skills.

OpenAI. (2025, July 17). ChatGPT Agent Unveiled: Transforming Workplace Productivity. Tom's Guide.

Reuters. (2024, Oct 21). Portugal Could Boost Productivity if One‑Third of Workforce Trained in AI.

Scientific Reports. (2025). Artificial Intelligence and the Well-Being of Workers.

Springer. (2025). Artificial Intelligence and Worker Stress: Evidence from Germany.

Comment