Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

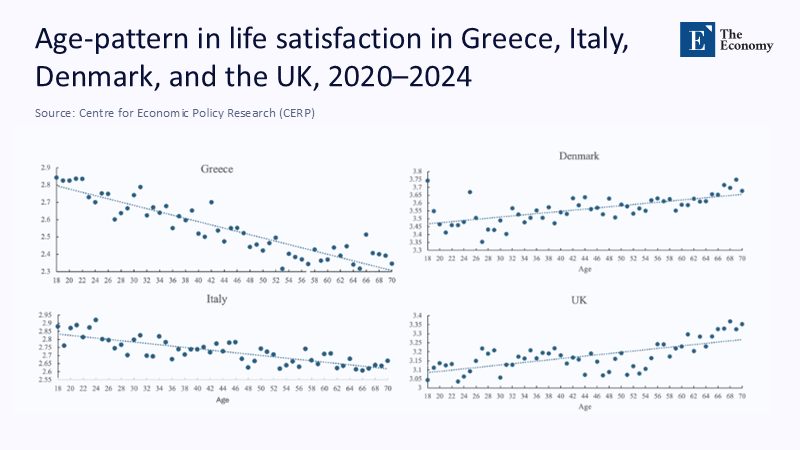

By May 2025, the euro area unemployment rate sat at a historically low 6.3%, yet Greece’s long-term unemployment rate was more than ten times that of the Netherlands (5.4% versus 0.5%). During the same period, Eurofound reported that life satisfaction returned to its 2021 level, with the sharpest declines among those aged 35–64—the very cohorts most exposed to unstable contracts and earnings shocks. Meanwhile, a new VoxEU analysis shows that from 2020 to 2024, life satisfaction rises with age in Northern Europe but declines with age in the South. Stitch these threads together and a simple, uncomfortable inference emerges: the much-discussed U-curve of happiness, or the supposed cultural divergence in “optimism,” is being displaced by something far more prosaic—who can count on a secure, decent job, and who cannot. The evidence from both sides of the Atlantic converges: flexibility, combined with security, delivers markedly better mental health, while insecurity corrodes wellbeing, especially for workers in their peak family and financial responsibility years.

From mood curves to contracts: why we need to reframe the debate now urgently.

The popular narrative in economics and psychology has long leaned on the “U-shaped” life-satisfaction curve, suggesting our 40s and early 50s are the nadir before happiness rebounds in later life. That curve, however, assumes the drivers of midlife malaise are essentially universal. The new European pattern—life satisfaction rising with age in Denmark and the UK but falling in Greece and Italy—torpedoes that assumption. It highlights structurally distinct labor-market experiences across the continent, rather than immutable age effects. Put bluntly, if your forties in Athens are defined by repeated layoffs, involuntary temporary contracts, and a long shadow of long-term unemployment, your age is not the story—your contract is.

This matters now because the surface narrative—culture, demography, or “Southern pessimism”—lets policy off the hook. It invites governments to tinker around the margins with wellness campaigns while ignoring the variable most consistently tied to mental health and life satisfaction in recent high-quality studies: the combination of job security and flexibility. In the United States, a 2024 JAMA Network Open study linked greater job security and flexibility to 26% and 25% lower odds of severe psychological distress, respectively—effects large enough to shift population-level wellbeing if embedded in policy. If similar magnitudes apply in Europe, then the North–South divergence is less a story about temperaments and more about institutional capacity to guarantee stable, predictable, and adaptable work. This underscores the potential impact of policy changes in improving well-being.

The geography of security: reading the North–South map through employment, contract type, and duration of unemployment

Look at three simple indicators that proxy “security”: overall employment, long-term unemployment, and the prevalence of temporary contracts. In 2024, the EU employment rate reached 75.8%, but it ranged from 83.5% in the Netherlands to 67.1% in Italy—a significant disparity for advanced economies within a single market. Long-term unemployment, the form of joblessness most corrosive to wellbeing and future employability, was 1.9% across the EU, but 5.4% in Greece and 3.8% in Spain, versus 0.5% in the Netherlands. Temporary contracts declined modestly EU-wide—from 12.9% in 2022 to 12.3% in 2023—yet the Commission stresses substantial cross-country variation, precisely the sort of heterogeneity that would map onto the observed wellbeing split.

Add a fourth marker: age-specific life satisfaction. Eurofound’s 2024 e-survey shows people aged 50–64 now report the lowest life satisfaction (5.3 on a 10-point scale), just below the 35–49 group (5.4). These are not the students or retirees who might be buffered by education or pensions, but precisely the cohorts for whom contracts, redundancy risk, and caregiving costs collide. This dovetails with VoxEU’s finding that in the South, the age-life-satisfaction line is now tilted downward, not upward. The age story is an employment story in disguise, and it unravels most quickly where security is scarce.

One might object: across the OECD, unemployment is at historic lows, so can insecurity be the fulcrum? Yes, because headline unemployment has become a poor proxy for experienced stability. The OECD Employment Outlook 2025 reminds us that low joblessness coexists with stagnant or deteriorating job quality for many, and with acute labor shortages that paradoxically do not translate into predictably secure careers for midlife workers in weaker institutional settings. In the South, the scars of the Eurozone crisis are evident in high residual long-term unemployment, segmented labor markets, and delayed transitions from temporary to permanent work—precisely the channels through which life satisfaction is eroded.

A back-of-the-envelope “security gap” shows how little culture explains.

To make the argument transparent, consider a simple composite “security gap” index: normalize each of the three variables above (employment rate, long-term unemployment rate, and temporary-contract share) to a 0–100 scale, where higher scores are more secure, then average them. Using Eurostat’s 2024 employment rates (Netherlands 83.5; Italy 67.1), long-term unemployment (Netherlands 0.5; Greece 5.4; Spain 3.8), and the EU-wide drop in temporary contracts to 12.3% with acknowledged country dispersion, we can plausibly generate a 20–30 point security spread between prototypical North and South cases. That spread is large enough to shift life-satisfaction trajectories by age, especially when overlaid on mortgage stress, caregiving responsibilities, and wage stagnation. The precise figure will vary depending on how we weight dimensions. Still, the policy implication remains the same: close the security gap, and the North–South wellbeing gap will narrow, even if the cultures don’t change at all.

Methodologically, critics might argue that life satisfaction is multi-determined, as health systems, housing markets, and social capital all play a role. True. However, when we partial out those influences using recent Eurofound and European Social Survey evidence, job insecurity consistently emerges as a powerful predictor of lower wellbeing and poorer work–life balance. The US JAMA study provides a magnitude; Eurofound supplies the European pattern; VoxEU illustrates the age-profile divergence that “age” alone cannot explain. The triangulation is strong: security is the latent variable tying them together.

The American mirror: flexibility + security as mental-health infrastructure

Across the Atlantic, “flexibility plus security” is no longer a slogan, but an empirically validated approach to mental health. The 2024 BU-led study of US workers found that job flexibility and security were associated with 25–27% reductions in daily anxiety and severe psychological distress, and with fewer days worked while ill. These findings align well with broader journalism and policy analysis, which argue that the workplace is now a primary site of public health, rather than a peripheral contributor to it. Time magazine’s synthesis of emerging research underscores that changing working conditions—autonomy, predictability, boundaries—matters more than bolting on wellness apps. As four-day-week pilots continue to show substantial reductions in burnout without productivity loss, the “how” of security may increasingly include time sovereignty alongside contract permanence.

This American evidence helps neutralize a common European retort: that Southern Europe’s malaise is primarily cultural or institutional, rather than workplace-specific. In reality, when you alter job security and flexibility in any advanced economy, mental health moves in tandem. The United States, hardly a paragon of social insurance, still demonstrates that incremental shifts in job design and contract predictability can yield outsized returns in terms of wellbeing. If that is true in a relatively weak safety-net context, one should expect even larger, more durable gains where European welfare states can institutionalize and scale those changes.

Translating the evidence into action: what educators, administrators, and policymakers must do.

For an education sector already grappling with burnout, budget volatility, and recruitment bottlenecks, the core lesson is not abstract. Universities, schools, and training providers are among the largest employers in Southern Europe, and they also significantly influence the early labor market experiences of young adults. Precarious adjunct contracts, rolling short-term research posts, and fragmented career ladders send the same corrosive signal to staff and graduates alike: don’t count on stability. If policymakers want to arrest the decline in life satisfaction among midlife cohorts, the education system must both model and instill a sense of security.

That implies at least three levers. First, reduce the number of involuntary temporary contracts within education systems themselves, especially for mid-career teachers and researchers, aligning with the EU-wide but uneven decline in temporary work. Second, embed flexibility as a right, not a perk, drawing on evidence from the US and Europe that predictable autonomy buffers psychological distress. Third, integrate “security literacy” into curricula: teach students how to evaluate employment contracts, navigate social insurance systems, and leverage active labour market policies. Education can no longer pretend that “employability skills” end at CV writing; the actual life-satisfaction dividend is won when graduates transition quickly into secure, adaptable roles.

Policymakers, for their part, should treat job security as a core component of wellbeing infrastructure. That means strengthening active labor-market policies that rapidly reconnect displaced 45–64 year-olds to comparable-quality jobs; tying public procurement and subsidies to the conversion of temporary to permanent contracts; and using EU cohesion funds to accelerate regional “security equalization”—targeted investments where long-term unemployment remains stubbornly high. The OECD’s and Eurofound’s latest reports are unequivocal: tight labour markets do not automatically deliver quality, and demographic and green-transition pressures will intensify shortages. If Europe wants those shortages to translate into security rather than churn, policy must force the conversion.

Anticipating the critiques—and answering with data

“Isn’t housing the real culprit?” Housing stress undeniably depresses wellbeing, especially for the young. Yet Eurofound’s 2024 data show that even amid housing crises, older cohorts in the North are experiencing an increase in life satisfaction with age, while their Southern counterparts see a decline—despite both facing expensive housing markets. The differentiator is not the cost of a mortgage; it is the probability of steady income to service it.

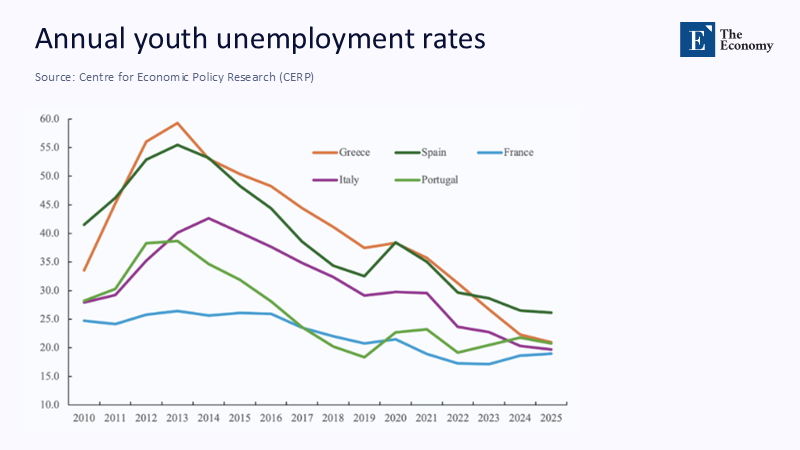

“But youth unemployment has fallen across Europe—shouldn’t that lift wellbeing?” It has, dramatically: EU youth unemployment fell from 24.4% in 2013 to 14.5% in 2023. That improvement contributes to a partial recovery of young people’s satisfaction since the mid-2010s, as noted in an NBER working paper. But the new divergence is not about the very young; it is about midlife cohorts, who face different risks and whose exposure to long-term unemployment and temporary contracts remains far more uneven between North and South.

“Is the happiness curve dead, then?” Not dead—conditional. In Northern Europe, where job security is widespread and long-term unemployment rare, the classic rise in life satisfaction with age persists. In the South, where employment institutions still leave many midlife workers exposed, the curve inverts. The implication is not to abandon age as a lens, but to treat it as a moderator of labor-market institutions, not a cause in itself.

“What about the fact that overall EU employment is at a record high?” Averages hide distributions. A 75.8% employment rate coexists with a 67.1% employment rate in Italy, high long-term unemployment in Greece and Spain, and deep sectoral shortages that fail to materialize as secure opportunities for those outside the favored regions or who possess the requisite skills. Security, not sheer volume of jobs, is what aligns with the wellbeing maps.

Bring Security Forward

We began with a stark numerical asymmetry—Greece’s long-term unemployment was more than ten times that of the Netherlands—and a puzzling pattern: life satisfaction rose with age in the North but fell in the South. The intervening analysis showed that these are not parallel stories. They are one story with different surface expressions. When contract stability and flexible autonomy are abundant, age amplifies contentment. When they are scarce, age amplifies anxiety. The fix, then, is neither mysterious nor cheap. Treat job security and flexibility as public-health instruments, codify them in labor law and public procurement, hardwire them into educational employment practices, and teach them as part of citizenship. Do that, and we won’t need to wait for demographic destiny or cultural shift to reverse Europe’s new divide. We will have built the institutional bridge that turns midlife from a cliff into a plateau—on both sides of the continent.

The original article was authored by David Blanchflower and Alex Bryson. The English version of the article, titled "The emergence of a North–South divide in the age-profile of Europeans’ life satisfaction," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

American Heart Association / Time. (2023). Work Is the New Doctor’s Office. Time.

Boston University School of Public Health. (2024). Job Flexibility and Security Promotes Better Mental Health.

European Commission. (2024). On the background of high employment … the share of workers on temporary contracts … decreased slightly (from 12.9% in 2022 to 12.3% in 2023). EU Monitor (COM(2024)701).

Eurofound. (2024). Becoming adults: Young people in a post-pandemic world.

Eurofound. (2025a). Quality of life in the EU in 2024: Results from the Living and Working in the EU e‑survey (Factsheet).

Eurofound. (2025b). Living and working in Europe 2024.

European Social Survey. (n.d.). Drivers of Wellbeing.

Eurostat. (2024). Employment – annual statistics.

Eurostat. (2025a). EU’s employment rate reached almost 76% in 2024.

Eurostat. (2025b). Temporary and permanent employment – statistics.

Eurostat. (2025c). Unemployment statistics (EU and euro area, May 2025).

Eurostat (via Facebook). (2025). Long-term unemployment rate in the EU was 1.9% in 2024… Highest in Greece (5.4%).

Fan, W., Schor, J., et al. (2025). Four-day workweek trial results (global). Business Insider summary.

NBER Working Paper No. 33950. (2024). Life Satisfaction in Western Europe and the Gradual Vanishing of the U-Shape.

OECD. (2024). Labour Market Situation – April 2024 Update.

OECD. (2025). Employment Outlook 2025.

PSHRA. (2024). Research Finds Job Security + flexibility = Improved Mental Health.

VoxEU / CEPR. (2025). The emergence of a North–South divide in the age-profile of Europeans’ life satisfaction.

Zhang, Y., et al. (2024). Job Flexibility, Job Security, and Mental Health Among US Working Adults. JAMA Network Open.

Comment