Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

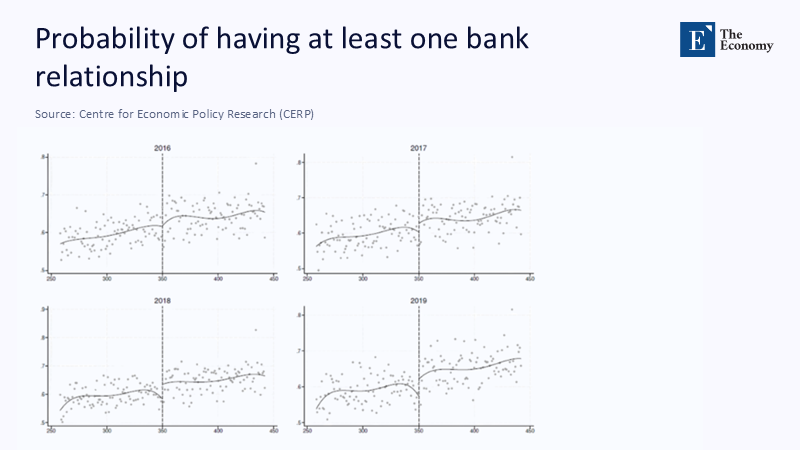

Italian micro-firms that accepted a 2016 option to strip words from their accounts didn’t save money. They lost the confidence of banks. In the most careful quasi-experiment on the question, Bank of Italy economists show that adopting the simplified textual regime reduced the probability of having at least one banking relationship by 17 percentage points by 2019—one-third of a standard deviation—with no measurable operating-cost savings. Investors, meanwhile, continue to say they want more, not fewer, explanations, and regulators from Rome to Washington are tightening the screws. This regulatory action is a clear signal that the market is now pricing opacity as a financing risk, not merely a disclosure choice. Accounting teams that still fight auditors line by line are no longer just guarding trade secrets; they are quietly taxing their firm’s access to growth capital. The fundamental policy question, therefore, is not whether transparency “costs too much,” but why we still let small and mid-sized enterprises believe they can economise on words without paying for it in interest rates, banking links, and investor trust.

From Compliance Cost to Credit Infrastructure: Reframing the Problem

The standard narrative treats disclosure as an administrative burden: text is compliance fluff, and accountants who pare it back are prudently saving scarce managerial time. The Italian reform proves the opposite. Words are not window dressing; they are part of the infrastructure that allows outside capital providers—especially banks that lend on thin margins and limited collateral—to price risk. When those words disappear, the pipes clog. The reform’s promise of lighter paperwork produced no statistically detectable decrease in firms’ operating costs. Still, it did result in a sharp and persistent decline in the extensive margin of bank credit. That asymmetry alters today’s policy calculus: regulators should account for the foregone financing capacity in any impact assessment that claims “reduced compliance costs.”

For educators and administrators who shape the next generation of accountants and auditors, the implication is immediate. Curricula and professional guidance must stop positioning textual disclosure as a discretionary add-on and present it instead as a priced asset in capital markets. Banks, investors, and even acquirers often treat narrative reporting as a substitute for due diligence when information is scarce. Italian micro-firms that withheld text saw slower ownership turnover, another sign that opacity hinders markets where reputation cannot carry all the weight. This underscores the urgency of the situation. We should teach CFOs that every paragraph they strike to “save costs” risks a larger, hidden cost of capital that compounds over time, emphasizing the crucial role of narrative transparency in capital markets.

What the Italian Quasi-Experiment Shows—and How

A 2016 law established a sharp size threshold, allowing eligible Italian micro-firms to omit the nota integrativa, a qualitative commentary that explains strategies, cost breakdowns, investments, and accounting choices. Researchers exploit that discontinuity in a regression discontinuity / sharp threshold setting to isolate the causal effect of fewer words. They show that take-up skews toward older, more productive, closely held firms in sectors less reliant on external finance, and in provinces served by local banks that rely on “soft information”—precisely the firms that believed they could “afford” opacity. But the credit-market penalty still arrived: a standard deviation increase in the probability of filing the simplified statement translated into a 17 percentage point drop in the likelihood of having at least one bank relationship by 2019, with no detectable fall in the ratio of total costs to sales or in line-item expenses like labour and services.

Two subtleties matter for the policy debate. First, once a firm already had at least one bank relationship, the amount of lending and the number of banking partners remained unchanged. Translation: reputation and track record can partially insure against silence, but not for the firms trying to start bank relationships—the very cohort policymakers say they want to help. Second, the ownership-turnover effect fades over longer horizons, suggesting markets eventually claw back some information through other means. But the intertemporal loss of financing options is not free, especially in a high-rate, risk-sensitive environment. That is why the Italian evidence should be read as a financing-access warning label on “simplified” reporting regimes across Europe’s SME landscape, just as the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) extends non-financial disclosure obligations downstream.

Banks, Investors, and the Audit Gap: The Market’s Patience with Opaqueness Is Over

If banks penalise opacity in SME textual reporting, investors are doing the same at scale. PwC’s 2024 Global Investor Survey reveals that a majority of investors anticipate growth but are increasing their demands for more transparent, decision-useful disclosure, including on sustainability and strategy. The gap between what companies say and what investors need is not shrinking; it is widening as macro volatility recedes and attention shifts back to firm-level execution and risk controls. Meanwhile, nearly a third of audits globally reveal deficiencies, according to recent analyses highlighted by Reuters, and three-quarters of the audits of UK companies that later failed did not identify any red flags—a catastrophic indictment of the “minimum viable disclosure” mindset.

Regulators have noticed. In the United States, the PCAOB, under Chair Erica Williams, has pushed to expand audit responsibilities, including fraud detection and the introduction of new transparency metrics. Auditors have balked, citing cost and mission creep. However, the Italian evidence strips away the pretense that opacity is benign: less narrative disclosure does impair stakeholder decision-making and limits access to capital. Investor groups broadly support the PCAOB’s direction for precisely this reason, and sustainability-focused watchdogs—from Deloitte/Fletcher’s 2023–24 work on disclosure to Carbon Tracker’s 2025 webinar series—are questioning whether current audit-practice transparency is sufficient to uphold investor confidence. The burden of proof has shifted. Opaqueness is now presumed harmful unless justified, not the other way around.

Operationalising Transparency: A Playbook for Auditors, CFOs, and Boards

The question for practice is no longer “should we disclose?” but “how do we disclose in ways that are fast, reliable, comparable, and audit-ready?” The CERTA framework provides a succinct starting point: standardise procedures; over-document; build clear communication channels; adopt advanced analytics, AI, and continuous auditing; and empower an independent audit committee that enforces objectivity. In a world where creditors and investors increasingly value softer, qualitative contexts, constant auditing and real-time anomaly detection are not luxuries; they are essential. They are what allow narrative transparency to be credible, not just verbose.

For educators, this means integrating data science into the audit curriculum, not as an elective but as the backbone of evidence-based transparency. For administrators, it demands a redesign of governance: audit committees require explicit mandates to challenge management on the sufficiency of narrative explanations, not merely the accuracy of numbers. For policymakers, this means subsidizing the fixed costs of tooling—such as template narrative sections, AI-assisted red-flagging, SME-ready XBRL, and sustainability taxonomies—so that the marginal cost of providing more information approaches zero. When the marginal cost drops, resistance from accounting teams loses its only plausible rationale.

Proportionality without Opacity: Calibrating CSRD, National SME Regimes, and Bank Supervision

Europe’s CSRD pushes non-financial disclosure deep into the SME chain. The proper response to the Italian evidence is not to exempt the smallest firms from words, but to craft proportional and structured words: concise yet decision-useful narrative templates that cover strategy, risks, accounting choices, and sustainability exposures in terms that investors and banks can understand. Italian supervisors are already grappling with governance and control weaknesses in smaller banks, as Banca d’Italia’s 2025 Financial Stability Report documents. High-quality, machine-readable SME narratives are complements, not substitutes, for stronger bank-side risk management—and both reduce the probability that relationship lending devolves into opaque, unscalable soft-information silos.

Critics will argue that disclosing granular qualitative information can leak competitive secrets or raise litigation risk. However, the Italian firms most likely to adopt opacity were older, more productive, and less reliant on external finance—the very companies best positioned to thrive on reputation and soft bank ties. Their experience still shows a financing penalty. That should tell policymakers that the equilibrium with minimal narrative disclosure is not only inequitable (hurting first-time borrowers most) but also inefficient (suppressing capital reallocation in precisely the parts of the economy that need it). The policy target, then, is simple: proportional transparency, guaranteed minimum narratives, and public tooling to keep compliance costs genuinely low.

Anticipating—and Disarming—the Pushback

Three objections recur. First, “transparency costs more than it’s worth.” The Italian result refutes this by finding no cost savings from cutting words, alongside a sizeable credit-access penalty. Second, “auditors are already failing; adding more words won’t help.” However, the audit failures that Reuters and others highlight are precisely why we need higher-quality, more assured narrative reporting, matched with PCAOB-style transparency about audit practices themselves. Without that, investors remain “absent stewards,” reappointing auditors that fail them, and markets continue to misprice risk until it is too late. Third, “small banks use soft information anyway, so words don’t matter.” The study shows adoption was more common in areas with small banks, but the credit penalty still materialised for firms without prior bank links. Soft information is no panacea in competitive, risk-averse lending markets.

Educators and professional bodies can counter these objections by teaching transparent cost-benefit methods: model the implied shadow cost of capital resulting from reduced disclosure, benchmark it against estimated compliance hours, and demonstrate—explicitly—that even modest financing penalties outweigh the accountant’s time saved. Policymakers can mandate disclosure of these internal calculations in board audit committee reports, forcing firms to defend opacity with numbers rather than instinct. Over time, that alone may realign incentives inside accounting departments that still reflexively resist surrendering details to auditors.

Stop Treating Disclosure as a Cost Centre; Start Treating It as Collateral

Italian micro-firms thought they could buy relief by deleting narrative explanations. They paid for it with lost bank relationships and stalled ownership churn, not with lower invoices to their accountants. Investors worldwide, chastened by recurring audit failures, are telling us the same thing: transparency is confidence, and confidence is capital. In 2025, that is not an abstract governance nostrum; it is an empirically quantified financing constraint. The correct response is not to rage against auditors or regulators, but to industrialise transparency—template it, digitise it, assure it, and teach it as the core of how firms earn trust. If we want cheaper capital for smaller firms, we should stop letting them economise on the very words that keep the credit pipes open. The call to action is simple: treat every omitted sentence as an interest-rate surcharge, and legislate, educate, and audit accordingly.

The original article was authored by Antonio Accetturo, an Economist at the Bank of Italy, along with four co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "The value of words: Evidence from non-financial disclosure regulation," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Accetturo, A., Baltrunaite, A., Cariola, G., Frigo, A., & Gallo, M. (2025). The value of words: Evidence from non-financial disclosure regulation. VoxEU, 22 July 2025. (See also CEPR Discussion Paper No. 20343).

Banca d’Italia. (2025). Financial Stability Report No. 1/2025.

Carbon Tracker. (2025). Investor confidence is built on transparency — but are current audit practice disclosures doing enough to uphold it? Webinar announcement, 22 July 2025.

CERTA. (2024). Key Steps to Enhance Audit Transparency in Your Organization. 10 February 2024.

Deloitte & The Fletcher School at Tufts University. (2024). With 4 Steps, Sustainability Disclosures Can Help Companies Earn Investor Trust. WSJ Custom Content.

PwC. (2024). Global Investor Survey 2024: Cautiously optimistic, investors expect growth. 4 December 2024. (See also PwC, What is top of mind for US investors in 2025).

Reuters Breakingviews. (2024). Guest view: Blame poor audits on absent investors. 3 July 2024.

The Wall Street Journal. (2024). Auditors Balk at Regulator’s Push to Expand Their Role. 2024.

Comment