Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

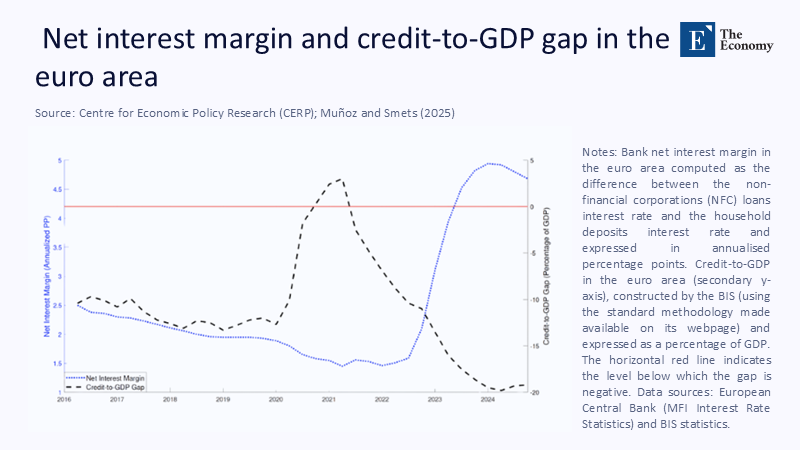

Across the European Union, banks closed 2024 with a sector-wide return on equity of nearly 10.5% and a net interest margin of around 1.66%, close to decade highs. Beneath those buoyant averages, early‑warning lights are flashing: Stage 2 loans—credits that have deteriorated significantly but are not yet non‑performing—reached roughly €1.57 trillion, or 9.7% of portfolios by year‑end. In comparison, ECB supervisory data indicate that the Stage 2 share was near 9.93% for significant institutions in the fourth quarter. In Japan, the central bank notes that default rates are higher than before the pandemic among firms whose profits have recovered slowly. In South Korea, authorities activated a 1% countercyclical capital buffer (CCyB) in 2024, and recent data indicate rising SME delinquencies, the worst in over eight years. These are not stray anecdotes. Today’s fat margins are the mirror image of borrowers’ heavier debt‑service loads—and history teaches that this margin‑debt squeeze often presages tomorrow’s credit losses. The policy choice is not whether to harvest windfalls, but where to keep them: in government budgets via one‑off levies, or inside banks as releasable capital before the rain arrives.

Reframing the policy choice: from windfall taxes to prudential retention

The public debate since 2023 has understandably focused on windfall taxes as bank profits surged, while households and smaller firms faced higher borrowing costs. Some European governments extended or introduced levies on banks—Spain’s temporary scheme, for example, set a 4.8% charge on net interest income plus fees for 2023–2024. However, redistribution through ex post taxation is a weak shock absorber; it cannot be “released” back into bank balance sheets when defaults rise. The more innovative architecture is prudential, not fiscal: capture a share of cyclical profits as releasable buffers that can be deployed precisely when stress materialises. The distinction matters. Taxes drain capital from the system; buffers fortify it. In the current late‑cycle landscape, every euro of windfall routed to treasuries is a euro not available to absorb credit losses if the delinquency tide comes in.

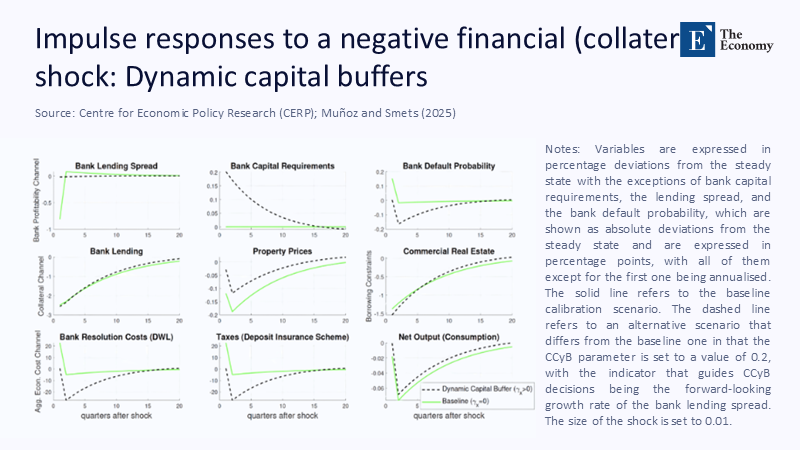

The supervisory community is already pivoting in this direction. In January 2025, the ECB and ESRB documented how 17 EEA countries have adopted a “positive neutral” approach to the CCyB—building a non-zero buffer early in the cycle so that it can be released quickly if conditions deteriorate. The associated research concludes that adopting a positive neutral CCyB does not increase peak-cycle requirements; it simply brings capital in sooner. In parallel, new modeling work by the Bank of England and a recent VoxEU/CEPR column formalise the core insight behind this pivot: build when there is headroom and you do not impair short‑term lending; resilience then supports lending at longer horizons. That is the policy frame this column advances—retain windfalls as buffers, not as taxes—because resilience, not revenue, is what borrowers will need if arrears climb.

Margins up, stress at the fringe: what the latest numbers reveal

The European Banking Authority’s 2024 wrap‑up is plain: profitability remains strong. The RoE for 2024 was 10.5%, and the NIM—after peaking—settled at around 1.66%. Asset quality headlines look benign, with NPL stocks near €375 billion, but the mix is less comforting: Stage 2 loans climbed to €1.57 trillion (9.7%), and commercial real‑estate ratios ticked up even as aggregate NPLs fell. ECB supervisory statistics for Q4 2024 echo the picture: Stage 2 shares are near 9.93%, SME NPL ratios are around the mid-4 % range, and the loan-to-deposit ratio is at a series low, reflecting steady deposits and sluggish credit growth. On the flow side, the July 2025 Bank Lending Survey reports that credit standards are broadly unchanged for firms, with demand only slightly firmer—a reminder that the perceived improvement in credit metrics partly reflects less origination to riskier borrowers.

Beyond Europe, the interest‑rate reset is now doing its slow work. The Bank of Japan’s April 2025 Financial System Report states that corporate default rates exceed pre‑pandemic levels for firms with weak profit recovery, and its micro evidence shows that a one percentage‑point increase in rates can lift mortgage probability of default by ~20 basis points for the average borrower, with worse outcomes where local labour markets are weak. In South Korea, where household and SME leverage are elevated, regulators activated a 1% CCyB in 2024; by May 2025, the won‑loan delinquency rate hit 0.64%, the worst in eight and a half years, with SME arrears surpassing 1% for the first time since 2017 and credit‑card delinquencies at a 20‑year high. This is the textbook late‑cycle pattern: headline profits hold, while stress accumulates at the margin.

Why high margins foreshadow higher delinquencies

The mechanism is straightforward. When policy rates rise, lending rates reprice more quickly than deposit rates, thereby widening banks’ net interest income. That spread is today’s profit. It is also tomorrow’s debt‑service strain for floating‑rate borrowers and for households and firms whose fixed‑rate debt resets with a lag. The ECB now estimates that higher mortgage payments will weigh on euro‑area consumption until 2030, even if policy rates are cut, because a large share of loans were originated during the low‑rate era and will roll over at higher rates. This asymmetric pass-through—profits first, borrower pain later—translates into a pipeline of future arrears that becomes visible in Stage 2 migrations before NPLs emerge. In other words, today’s margin windfall is the leading edge of tomorrow’s loss curve.

Modern macro-prudential models explicitly capture this dynamic. The positive neutral CCyB literature argues that margins and early asset-quality indicators provide sufficient signals to justify building releasable buffers before losses materialize; doing so does not dampen short-term lending and, by lowering the probability of a crunch, supports borrowing over the medium term. The VoxEU/CEPR column summarises the evidence; the Bank of England working paper formalises it; and the ECB/ESRB joint report codifies it into guidance used by an increasing number of national authorities. The theory and the data point in the same direction: retain a slice of the windfall while the system still has headroom.

A rule for this cycle: the Profit‑to‑Risk Buffer (PRB)

A simple, transparent Profit‑to‑Risk Buffer (PRB) rule operationalises this strategy. Set a neutral band for sector‑wide NIM—for example, 1.50–1.70% in the euro area based on recent aggregates. When NIM exceeds the band for two consecutive quarters, banks retain a fixed share of the excess NIM as a mix of releasable capital (via the CCyB) and forward‑looking provisions. Define automatic release conditions tied to observable risk indicators—for instance, the Stage 2 share falling below 8% for two consecutive quarters and CRE asset quality stabilizing. Because the triggers are public statistics, both build‑up and release are predictable, reducing policy uncertainty for investors and allowing dividends to resume quickly once the signal improves. The point is not to suppress lending; it is to finance resilience out of cyclical profits instead of after the fact.

How significant is the retention? Use aggregates to illustrate orders of magnitude—not to replace supervisory calibration. EBA data indicate that Stage 2 loans will be approximately €1.57 trillion (9.7%) at the end of 2024. If we apply a conservative incremental expected‑loss rate of 1.25% to that stock—recognising Stage 2 loans are still performing—that implies ~€19.6 billion of additional loss‑absorption capacity to hold system‑wide. A mild‑stress overlay of 2.5% yields ~€39 billion. On the capacity side, the total assets of EU/EEA banks were approximately €28.2 trillion as of December 2024. Treating that as a proxy for interest‑earning assets (a conservative simplification), six basis points of “excess NIM” above a 1.60% reference would generate about €16–17 billion in a year. Retaining 60% under a PRB could prefund the conservative overlay in roughly a year and the mild-stress case over about three years—without new levies.

Method transparency. The overlay rates sit below through‑the‑cycle loss assumptions used in stress tests and below average LGD for unsecured SME credit, by design. Using total assets as the NIM base understates capacity when cash and non-interest-earning assets are abundant; supervisors would replace this proxy with measured interest-earning assets at the jurisdictional and bank levels. The intent is clarity: the PRB scales with margins and with risk signals that already sit on supervisory dashboards.

Implications for practice: educators, administrators, and policymakers

For educators and curriculum designers in economics and finance, the PRB serves as a teachable link between monetary pass-through and macroprudential design. Students can simulate how a few basis points of NIM excess convert into billions of releasable capital using the EBA and ECB series for NIM, Stage 2 shares, and NPLs. They can then map ECB lending‑survey signals into release decisions and compare model‑implied buffers with actual national CCyB paths. The exercise crystallises a key policy lesson: buffer policy is most effective when it is formulaic, forward‑looking, and releasable.

For institutional administrators—such as universities, hospitals, and education nonprofits—that borrow in bank markets, the message is to plan for pro-cyclical costs, even if policy rates drift downward. The ECB expects mortgage resets and higher servicing costs to continue to drag on consumption through 2030, and similar reset dynamics are expected to affect corporate borrowers with floating-rate or short-maturity debt. A PRB regime increases the likelihood that supervisors will release capital when arrears rise, thereby moderating any abrupt contraction in credit supply. That is directly relevant to organisations that time bond issues, refinancings, or capital projects to windows of stable spreads and bank capacity.

For policymakers, the PRB offers a superior alternative to windfall taxes if the goal is to shield the real economy from the next credit chill. VoxEU/CEPR summarises the evidence that building with headroom does not harm near‑term lending and supports it over time. The ECB/ESRB positive-neutral framework provides a ready home for PRB-style retention, while national authorities can calibrate country-specific triggers and communicate them through quarterly CCyB decisions. The outcome is the same social contract promised by windfall taxes—that extraordinary profits serve the public interest—but achieved within the safety system, where resources can absorb losses rather than fund unrelated outlays.

Anticipating critiques—and how to implement anyway

“Won’t this suppress lending when growth is already soft?” The model-based and empirical records now suggest that building releasable buffers when banks have headroom does not reduce short-term lending, but rather tends to increase it at longer horizons by lowering the odds of a credit crunch. That view is embedded in the ECB/ESRB guidance and reinforced by the Bank of England. Moreover, the PRB is state‑contingent: retention switches off as margins normalise and switches to release when risk indicators ease.

“Margins are already coming off; isn’t the window closing?” EBA data show NIM slipped from its peak but remains within a high historical band. The PRB is tied to excess NIM, so retention automatically declines as the spread compresses; there is no permanent throttle on payouts. Indeed, codifying the rule reduces political pressure for ad hoc levies precisely because investors can incorporate the formula into their pricing. Where buffers are already building—the Netherlands 2% CCyB, Greece’s positive‑neutral framework—a PRB can nest within existing policy and sunset windfall levies as prudential retention takes over.

A practical blueprint fits on one page. Calibrate the neutral NIM band using supervisory statistics; set retention as a fixed share of “excess NIM” sustained over two quarters; define releases based on Stage 2 and CRE metrics; and publish a dashboard alongside CCyB decisions. In Europe, start with a trial NIM band of 1.50–1.70%, an 8% Stage 2 release threshold, and update semiannually. For Japan, lengthen the look-back window to reflect slower pass-through and the prevalence of fixed-rate loans. For South Korea, embed the PRB within the 1% CCyB while monitoring SME and card‑credit delinquency. The aim is credibility: when the indicators improve, release; otherwise, keep building. That is how releasable capital, not budgets, will cushion the next turn of the cycle.

Keep the umbrella where the rain will fall

The late‑cycle juxtaposition is stark: healthy bank margins and tight cash flows for marginal borrowers. Europe’s 2024 profitability figures, Japan’s evidence on default dynamics among weaker firms, and Korea’s climbing SME delinquencies all point to the same asymmetry—profits now, pain later. The responsible answer is neither to moralise about profits nor to siphon them off to treasuries, but to hold a measured share inside banks as releasable buffers. A Profit‑to‑Risk Buffer rule makes that choice automatic: build in good times when NIM runs hot; release when Stage 2 and sectoral risk indicators say the storm has passed. That is how to convert extraordinary earnings into ordinary resilience. Done now—before arrears bite—it will spare households, SMEs, schools, and hospitals from the worst of the next credit chill and turn a fragile expansion into a sturdier recovery. It is a policy choice available this year. The only question is whether we use it.

The original article was authored by Manuel A. Muñoz and Frank Smets. The English version, titled "Macroprudential policy for banks: Build the countercyclical capital buffer when there is headroom for doing so," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Bank of England. (2025). The positive neutral countercyclical capital buffer (Working Paper).

Bank of Greece. (2024, October 18). Countercyclical capital buffer rate set at 0.25%, applicable from October 1, 2025.

Banking Supervision, European Central Bank. (2025, March 20). ECB publishes supervisory banking statistics on significant institutions for Q4 2024.

Banking Supervision, European Central Bank. (2025, March 20). Press release (PDF version).

Bank of Japan. (2025, April). Financial System Report (April 2025).

BusinessKorea. (2025, July 25). Bank Loan Delinquency Rate Rises to 0.64% in May

EBA. (2025, March 21). EU/EEA banking sector remains stable… (Q4 2024 Risk Dashboard press release).

EBA. (2024–2025). EU/EEA banks’ profitability holding up despite declining NIM.

EBA. (2025). Asset side –

ECB & ESRB. (2025, January 31). Using the countercyclical capital buffer to build up resilience early in the cycle (Joint report).

European Central Bank. (2025, July 22). Euro area bank lending survey (Q2 2025).

Financial Services Commission (Korea). (2023, May 24). Activation of the 1% CCyB (from May 2024).

Maeil Business Newspaper (mk.co.kr). (2025, July 25). The delinquency rate of local banks’ won loans continued to rise…

Reuters. (2025, June 18). Mortgages to weigh on euro zone consumption until 2030, ECB says.

Tax Foundation. (2024, September). Windfall profit taxes in Europe (including banking levies).

VoxEU/CEPR. (2025). Macroprudential policy for banks: Build the CCyB when there is headroom.

Comment