Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

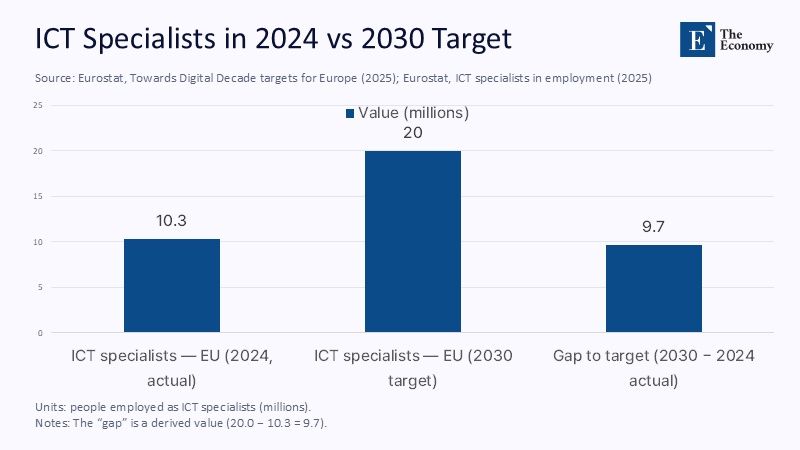

The European Union employs 10.3 million ICT specialists, yet it remains 9.7 million short of its own 2030 Digital Decade goal. That is a gap larger than the entire tech workforce of many member states combined. Meanwhile, India contributes approximately 23% of the world’s growth in working-age population, a demographic engine that no other major economy can match. This year, transatlantic politics raised the stakes: on 27 July 2025, Washington and Brussels agreed on a 15% tariff on most EU goods to avert a trade war, confirming that US leverage over Europe is not a passing squall. Four days earlier, India and the UK signed a comprehensive free-trade agreement, positioning London at the front of the queue for market access and talent pipelines into India. With Russia weaponizing energy and China aligning itself closer to Moscow, Europe cannot hedge its bets by deepening its dependence on Beijing. It needs a partner that enlarges its room for maneuver. That partner—on timelines that matter—is India.

Reframing the Question: From “Which Market?” to “Which Ally Against Both the US and Russia?”

Europe’s dilemma is not simply where to sell more goods. It is about preserving strategic autonomy when two giant powers can squeeze it—one with tariffs and industrial policy, the other with shells and pipelines. The United States just codified a 15% tariff baseline; even if some sectors escape, the new normal is explicit dependence on American domestic politics. Russia’s aggression ensures European energy vulnerability, and sanction friction will persist for years. China, for all its market size, has moved closer to Moscow, renewed its “no‑limits” rhetoric, and sits in the EU’s crosshairs for anti‑subsidy actions on electric vehicles, making a full‑tilt pivot to Beijing neither politically nor economically sustainable. In this configuration, India is the only plausible large-market ally that can help Europe mitigate US tariff pressure while limiting exposure to Russia’s war economy and China’s overcapacity.

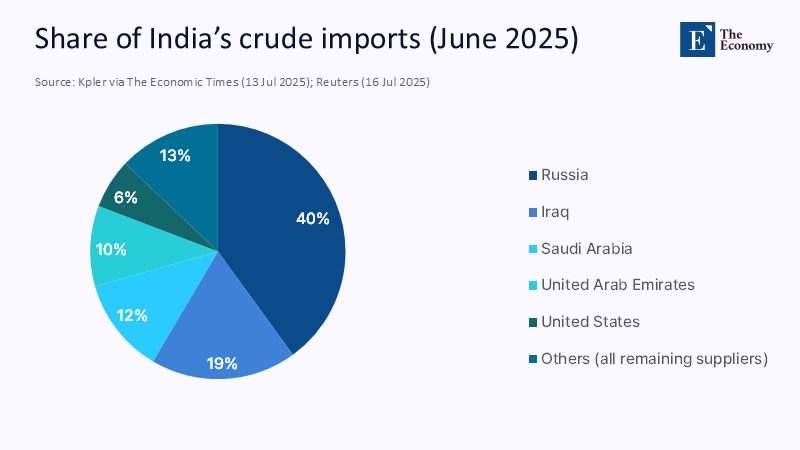

India is not a mirror‑image counterweight to Washington, and that is an advantage. New Delhi’s foreign-policy posture is multi-aligned rather than anti-American; it cooperates closely with the US on technology and defense, even as it buys discounted Russian crude, from which Russia supplied roughly 35% of India’s oil imports in January–June 2025. This posture keeps India from being absorbed into any single bloc—and keeps it viable as a balancing ally to Europe. The policy implication is to prioritize a deal structure that advances European resilience without requiring India to sever ties that the EU itself cannot sever for others. That means foregrounding education, talent mobility, and rules for trusted technology as the first deliverables, while tariff and market‑access chapters catch up. Sequencing the partnership this way makes the alignment durable across changing governments in Washington and New Delhi and robust to Kremlin adventurism.

The Evidence of Urgency: Numbers That Should Focus Minds

The trade logic is strong but incomplete. In 2023, the EU was India’s largest trading partner, with €124 billion in goods trade and €59.7 billion in services. Negotiations for a comprehensive agreement restarted in June 2022 and have advanced through 11 rounds as of May 2025, with several technical chapters reportedly closed. Yet differences persist, including Indian concerns over proposed EU oversight of capital‑flow measures. The target to finish by the end of 2025 survives, but every month of delay compounds the costs of being beaten to market by the UK‑India FTA, signed on 24 July 2025. In a world where tariffs can change with a press conference, Europe needs a hedge it can implement in academic time, not diplomatic time.

Geopolitics reinforces the clock. India’s refiners continue to process large volumes of Russian crude, and the EU has recently moved to close the refined-products loophole that allowed Russian oil to reach Europe via third countries, including India. That step is strategically coherent, but it will disrupt trade patterns for months. Meanwhile, the India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC)—a sea-rail-energy-data link that could eventually cut costs—remains hostage to instability in West Asia; even its proponents concede it is a decade-scale bet. None of this argues against an EU–India deal; it argues for a people‑first on‑ramp whose costs are modest and whose benefits are broadly distributed across member states long before customs schedules are harmonized.

The Policy Answer: A Strategic Education and Talent Compact—First

Suppose the EU needs India to counterbalance US tariff power and Russian leverage. In that case, the first deliverable should be a Strategic Education and Talent Compact that can be launched this academic year and scaled over the next 18–24 months. The foundation is already there. The EU has a legal framework for micro-credentials that enables cross-border recognition of short, skill-specific modules. The EU–India Trade and Technology Council has workstreams on AI, semiconductors, and resilient value chains.

Additionally, the recast EU Blue Card lowers salary thresholds while maintaining national control over admissions. India, for its part, has accelerated tech‑policy capacity and is investing in AI and digital public infrastructure. Stitch these pieces into one protocol: mutual recognition for priority engineering and computing degrees plus co‑taught micro‑credentials; a continent‑wide Blue‑Card fast lane for verified shortage occupations; and joint research clusters in battery recycling, power electronics, AI safety, and hydrogen systems, each with associated mobility visas.

The human‑capital arithmetic is favorable and transparent. The EU employed 10.3 million ICT specialists in 2024—about 5.0% of total employment—and is still 9.7 million short of its 2030 goal. In 2023, member states issued approximately 89,000 EU Blue Cards, with 78% of these being issued in Germany. This concentration indicates both high demand and an opportunity to spread the benefits more widely. Student flows are on the rise: 49,483 Indian students were enrolled in German universities during the 2023/24 winter semester, while France has publicly set a target to host 30,000 Indian students by 2030, with a preparatory program launched in 2024. A conservative scenario that converts 50,000 India‑to‑EU graduates per year into early‑career roles by 2028—with 70–80% retention in ICT‑adjacent jobs—would close 0.35–0.40 percentage points of the Digital Decade skills gap annually. The assumption scales present student numbers and Blue Card baselines, taking into account dropout, sectoral switching, and return migration.

Broadening the Coalition: From a Few Trade Winners to Many Talent Winners

One reason the trade track alone struggles is distribution. Parliamentary analysis estimates welfare gains for the EU of about €8–8.5 billion in modeled scenarios—roughly 0.03% of EU GDP—with gains concentrated in specific sectors and member states. That is not a political juggernaut. A talent compact flips the calculus by creating visible benefits in every region that hosts universities, research labs, and SMEs. Ring‑fence a share of scholarships and placements for Southern and Eastern Europe, where working‑age populations are shrinking fastest, and link every mobility channel to local upskilling commitments. Because the compact relies on distributed institutions—such as universities, apprenticeships, and regional innovation hubs—it produces more and more geographically balanced beneficiaries than tariff preferences ever can at the outset. That is how to build the majority required to pass the more contentious market‑access chapters.

A simple arithmetic check shows why this matters. Fund 20,000 joint EU–India master’s seats annually in digital, green, and health fields, target a 60% post-graduation retention rate for at least five years, and add 2,000 cotutelle PhDs tied to industrial labs. Even discounting non-ICT fields, Europe would add tens of thousands of early-career specialists annually, while creating alum networks in India that foster two-way innovation. Publish quarterly dashboards of visa processing times, enrollment by region and discipline, cohort retention, and gender balance—a serious gap, since women account for just 19.5% of EU ICT specialists. Transparent metrics and regional allocation mitigate the concern that mobility benefits will concentrate solely in Berlin or Paris. They also provide policymakers with a way to adjust quotas—up or down—with public confidence.

Answering the Obvious Critiques

“India is too close to Russia.” It is true that Russia was India’s top crude supplier in H1 2025, accounting for roughly 35% of imports, and that Indian refiners took advantage of the discounts. The EU’s newest sanctions now ban refined products made from Russian crude—including those routed through third countries—shrinking that arbitrage and realigning some flows to the Gulf. But energy tactically complicates, rather than strategically precludes, partnership. A people-first compact is the least exposed element of the relationship to oil markets; it also embodies values clauses in research integrity, labor standards, and dual-use safeguards, without making climate-critical cooperation hostages to refinery input slates.

“Mode‑4 mobility is a political third rail.” It can be if unmanaged. Yet the recast EU Blue Card already lowers salary thresholds and clarifies qualifications while preserving member‑state control. A compact can include occupation-specific quotas, salary floors indexed to national medians, and two-way mobility and return pathways that address concerns about brain drain in India and local labor market anxieties in Europe. Tie every fast lane to verified shortage lists, combine with funded upskilling for domestic workers, and publish outcomes. The result is positive‑sum: fewer unfilled vacancies, speedier diffusion of techniques from labs to shop floors, and a defensible narrative that Europe is investing in its people at the same time as it welcomes others.

“The UK has leapt ahead, so Brussels is relegated to second place.” The UK–India FTA is real and a wake‑up call. But the EU can still win the arena that will matter most for the next five years: talent formation and standards. Europe offers a continental skills market governed by the world’s most mature data‑protection regime, a research ecosystem second only to the US, and an increasingly interoperable digital public infrastructure that can mesh with elements of India Stack. Recent moves—such as UPI acceptance at the Eiffel Tower and Paris retailers—show how quickly technical interoperability can scale once frameworks are established. A September‑ready admissions and visa fast lane, plus mutual recognition of micro‑credentials in AI and power electronics by spring 2026, would send a louder signal to Indian students and firms than tariff draft texts ever could.

“The India–Middle East–Europe Corridor is too fragile to bank on.” The corridor will rise or fall about Middle East security trends that no Brussels negotiator can control. However, IMEC is a decade-scale logistics bet; a talent compact is a two-year implementation bet. The latter does not need to wait on the former—skills, research standards, and interoperable identity and payments systems will make any eventual corridor more credible when geopolitics permits. Europe should support IMEC intellectually and diplomatically while focusing on the people aspect now.

Delivering in Academic Time: A Realistic Sequence and Timetables

What should be done, and when? First, by January 2026, stand up a pan‑EU admissions and visa fast lane for Indian students in priority fields—AI, cybersecurity, power electronics, battery chemistry, clinical data science—with harmonized document requirements and processing SLAs aligned to university calendars. Second, by September 2026, finalize mutual recognition of co‑taught micro‑credentials and degree‑level qualifications under the EU’s 2022 framework, publishing joint implementation guidance that universities and employers can adopt without bespoke negotiations. Third, by early 2027, launch a Blue‑Channel pathway that converts qualifying diplomas or research contracts into streamlined residence and work authorization with ring‑fenced quotas for regions facing the steepest working‑age declines. These three milestones are administratively tractable and compatible with the longer, harder chapters on agriculture, pharmaceuticals, and procurement that will define the full FTA.

Financing can be modest but catalytic: braid resources from Erasmus+, Horizon Europe instruments, and InvestEU, and require match‑funding from industry in exchange for structured recruitment access and IP sharing under standard EU templates. Add quarterly dashboards so the public can track performance and course-correct, including visa times, enrollment by discipline and region, share of graduates entering EU jobs, retention rates after two and five years, and the gender distribution in ICT cohorts, where women currently make up just 19.5% of specialists. When skeptics ask what Europe gains now, this dashboard will answer in real numbers long before the tariff schedules are fully settled. Meanwhile, the trade table should continue to move forward; the Commission remains the best venue to establish transparent rules on data, competition, and investment that outlast the tenure of personalities in Washington or New Delhi.

Make the Ally, Then the Agreement

Return to the arithmetic that should anchor European strategy. The bloc is 9.7 million ICT specialists short of its 2030 ambition; India supplies roughly a quarter of the world’s growth in working‑age population; the US has moved to a 15% tariff baseline that could tighten again; and the UK–India deal will channel trade and talent through London unless Brussels responds at speed. The rational response is not to postpone the partnership until every tariff line is tidied up; it is to front‑load people and knowledge so strategic gains arrive within academic cycles, not electoral ones. A fast, rules‑anchored EU–India talent compact would help Europe hedge US tariff risk, reduce structural exposure to Russia and China, and widen the coalition for an ambitious trade pillar. It would also demonstrate, in the most practical way possible, that Europe still knows how to compete: by training, attracting, and empowering people on a continental scale—and doing it now.

The original article was authored by Sangeeta Khorana, a Professor in International Trade Policy in the Department of Economics and International Business at Aston Business School. The English version, titled "Racing against time for an EU–India trade deal," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Atlantic Council. (2025). It is Europe’s time to shine on IMEC.

Bruegel. (2025). The time is right to make a European Union–India trade deal happen.

Council on Foreign Relations. (2025). No Limits? The China‑Russia Relationship and US Foreign Policy.

European Commission. (2024). Provisional duties on battery electric vehicles from China (Press release).

European Commission. (n.d.). Europe’s Digital Decade: 2030 targets.

European Commission—DG Trade. (2025). EU–India agreements; trade statistics and negotiation status.

European Parliament Research Service (EPRS). (2024). EU–India free trade agreement: potential effects (Briefing 757588).

Eurostat. (2024–2025). ICT specialists in employment; Towards Digital Decade targets; Blue Cards 2023; Rising share of ICT specialists.

ICMPD & ILO. (2023–2025). India–EU Cooperation and Dialogue on Migration and Mobility (Phase II).

IEA. (2025). Oil Market Report—July 2025.

Legislative Train Schedule—European Parliament. (2025). EU–India FTA: eleventh round in May 2025.

Lyra & NPCI International. (2024). UPI accepted in France (Eiffel Tower; Galeries Lafayette).

Press Information Bureau, Government of India. (2025). India–UK Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement: signing materials.

PRB (Population Reference Bureau). (2023). India’s contribution to growth in the global working‑age population (23%).

Reuters. (2025). US–EU strike deal with 15% tariff; EU closes refined‑products loophole; India’s Russian oil share; UK–India FTA signing; EU–India FTA negotiations updates.

Trade and Technology Council—European Commission. (2025). Second EU–India TTC meeting: joint statement and tech priorities.

UK Government. (2025). UK–India trade deal: treaty materials and announcement of investment wins.

WEF. (2025). What to know about an EU–India free trade agreement (2025 update).

Comment