Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

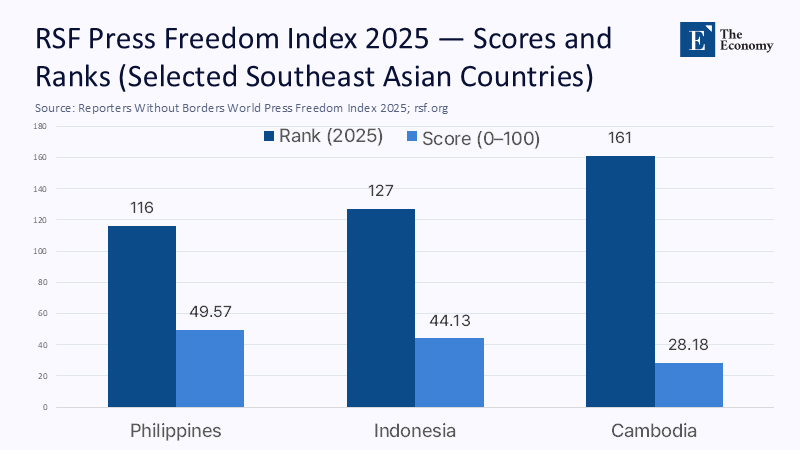

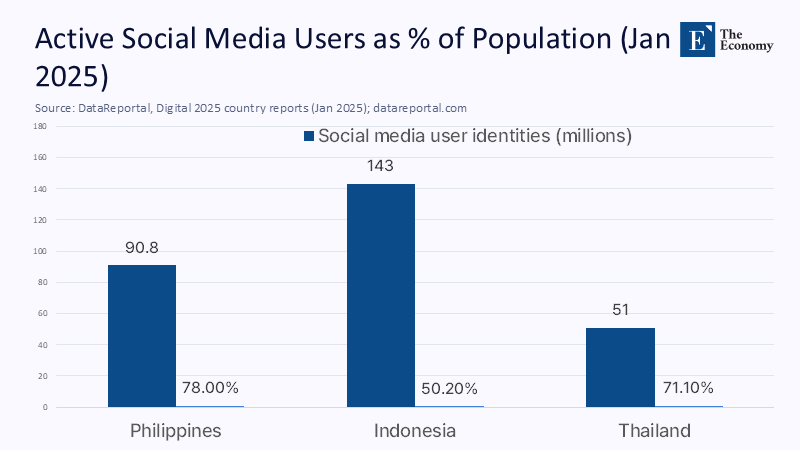

By June 2025, the share of Filipinos who said online falsehoods are a pressing problem reached 67%, the highest on record. At the same time, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) concluded that the global conditions for journalism had deteriorated so far that the world’s overall press‑freedom environment is now classified as “difficult”—and it singled out economic fragility as the leading threat. Within Southeast Asia, key democracies rank relatively low, with the Philippines at 116th, Indonesia at 127th, and Cambodia at 161st. Meanwhile, social media is the region’s daily water supply: recent analyses estimate roughly 64% of Southeast Asians are active users, outpacing the global average. The familiar conclusion follows with new urgency: the style of misinformation perfected in the United States and Europe now distorts public opinion in Southeast Asia, but it is doing so in countries where the institutions that correct falsehoods—independent newsrooms, transparent advertising, and enforceable data access—are thinner. The fix can’t be more whack‑a‑mole moderation. It must be to rebuild the information economies that make truth findable and valuable.

Reframing the Diagnosis: Not a Content Problem, an Information‑Market Failure

The instinct is to treat disinformation as a content disease: remove the false posts, fact‑check the viral hoaxes, tweak a recommendation system, repeat. But the same tactics now deforming Southeast Asian politics point to a deeper failure—weak information markets. RSF’s 2025 findings make this plain: the global press‑freedom score has sunk into “difficult” territory for the first time, with economic pressure—not just arrests—eroding scrutiny. In places where investigative capacity is undercapitalized, ownership is concentrated, and legal defenses are patchy, copy-pasted manipulations imported from the West have a greater impact and last longer. In other words, the lie machine is familiar; the immune system is not. Treating the feed while starving the watchdog only ensures that the next iteration—AI-filtered voices, meme-based dog whistles, coordinated edits—arrives faster than any takedown regime can.

This reframing is critical now because platform governance is diverging. The European Union is operationalizing the Digital Services Act into election‑risk guidelines, an election “toolkit” for regulators, and—crucially—a delegated act for researcher data access that pries open ad libraries and enforcement claims. Southeast Asia, by contrast, relies on episodic pressure and ad hoc takedowns, often without independent auditing. The region does not need to copy and paste European law. Still, it does require the economic muscle—funded journalism, enforceable transparency, and stable research access—that makes course correction credible.

The Philippines as Harbinger: High Alarm, Thin Guardrails

The Philippines illustrates the paradox. Public alarm is high—67% of Filipinos express concern about online misinformation and disinformation—but institutional guardrails are lagging. In May 2025, a delegation of Southeast Asian lawmakers initiated a study visit focused on dynasties, state resource abuse, violence, and online disinformation, underscoring how political incentives can ride the wave rather than resist it. Meanwhile, independent fact-checkers continued to debunk manipulated clips circulating across Facebook, YouTube, and messaging apps, with a limited impact on the campaign's consequences. Warnings abound; leverage is scarce.

The state’s tactical playbook—lean on platforms—shows both energy and limits. In May, the Department of Information and Communications Technology boasted that Meta removals of election‑related falsehoods were occurring within an hour, a speedup credited to regulatory pressure. Rapid takedowns can staunch episodic harms, but without transparent ad libraries, archived creatives, and researcher access on a deadline, the deeper drivers—coordinated inauthentic behavior and pay‑to‑play amplification—remain obscured. The public recognizes the problem; institutions must now change the incentives that sustain it.

Indonesia’s Lesson: Familiar Tricks, Region‑Specific Consequences

Indonesia’s 2024 cycle did not pioneer manipulation; it localized it. Research and reportage describe professionalized “buzzer” markets and influencer pipelines that rebranded reputational liabilities through affective, AI-mediated imagery. This now-famous gemoy aesthetic softened hard edges and appealed to younger voters. Studies document exposure to manipulated narratives, while field accounts connect deepfake experiments—such as Suharto being revived to urge support and cartoon avatars dancing with cats—to concrete persuasion targets on TikTok and beyond. The patterns echo the United States and Europe. What differs is the thinner layer of counter‑vailing journalism and the absence of enforceable disclosure about who pays whom to manufacture virality.

Those differences matter because they shift the cost curve. When cute‑aggression visuals and short‑form spectacle outpace sober scrutiny, the center of gravity moves from issues to vibes. Newsrooms with little investigative bandwidth can’t consistently “follow the money” into creator farms or ad‑tech contractors. And legal regimes built for television struggle to surface the supply chain of persuasion across micro‑influencers, agencies, and automation tools. The result is a market where distortion is cheaper than verification—a dynamic worsened by data hoarding and fragmentary transparency. Without economic reinvestment in scrutiny and rules that expose who funds attention, democratic choices will continue to tilt toward aestheticized narratives.

Why Western Corrections Won’t Suffice: The Accountability Gap

It is tempting to argue that Western democracies also endured waves of falsehoods and, over time, developed antibodies—fact‑checking teams, platform policies, media literacy efforts. The difference is that Europe added teeth. Under the DSA, platforms must treat elections as systemic risk problems, complete formal risk assessments, ensure ad library transparency, and grant researchers access to non-public data. In late 2024 and 2025, the Commission escalated by opening proceedings against TikTok over election risks and ad transparency, and by publishing an elections toolkit to guide national regulators. These moves do not eliminate manipulation, but they increase the cost of industrializing it and establish a baseline for independent verification.

Most Southeast Asian governments lack parallel tools, and many news markets lack the economic resilience to deliver sustained scrutiny. RSF’s 2025 analysis frames this as a structural, not episodic, problem. In this context, platform press releases—such as Singapore’s Election Centre on TikTok—may help with user education and policy signaling, but cannot replace enforceable transparency. Without researcher access, standardized ad-library fields, and auditable vendor disclosures, “election hubs” are public relations assets, not public interest safeguards. The policy lesson is not to import Western rules wholesale but to outpace Western timelines by investing in the institutions that make corrections credible.

From Evidence to Action: A Practical Package with Costs and Payoffs

First, countries should negotiate Election Integrity Compacts (EICs) with major platforms for the 90 days preceding and the 30 days following elections. These compacts would require a 24/7 incident desk, ad-library fields that meet DSA-grade standards (payer identity, spend, creative, target segments, timestamps), and researcher data access within 72 hours for flagged risks. Costs are manageable. A conservative model—encompassing 30 specialists per country (policy analysts, forensic investigators, and local-language linguists) on rotating shifts at an average fully loaded cost of US$60,000—is estimated to cost US$1.8 million per country per year. Scaling across the ten ASEAN states suggests ~US$18 million annually. These are transparent estimates based on regional salary bands and election-window staffing needs; governments and civil society can refine the calculus using national pay scales and caseload histories. The point is feasibility: a modest premium that buys systemic responsiveness rather than sporadic outrage cycles. (Estimate.)

Second, establish an Independent Press Capacity Fund (IPCF) financed by a two-basis-point (0.02%) levy on national advertising markets, platform-agnostic, and administered by a university–civil society consortium insulated from executive control. Global ad-spend baselines make this viable: credible forecasts project 2024 spend at nearly US$1.1 trillion and 2025 at around that mark, with roughly three-quarters of the spend digital. Even small national shares could yield US$8–12 million annually for investigative desks, legal defense pools, safety training, and local‑language fact‑checking. The methodology applies conservative national ad-revenue shares, allocating 40–50% to investigative capacity, 20–30% to legal defense and safety, and the remainder to collaborative fact-checking networks. Governments should publish annual audits. The economic fix—re-capitalizing scrutiny—enables the content fix to take hold.

Third, require vendor-transparency registries for digital campaigning: campaigns must disclose the use of automation tools, influencer contracts, creative agencies, and intermediaries, along with auditable identifiers. Indonesia’s scholarship on buzzer networks reveals how professionalized these markets have become; sunlight exposes price manipulation and provides watchdogs with a map. Penalties should be tied to public subsidy eligibility or ballot access, rather than speech controls, aligning incentives without delegating authority to ministries to adjudicate truth.

Finally, prebunk at scale during the fortnight leading up to voting. The best evidence suggests that short, tactic-focused videos—teaching how scapegoating, conspiratorial frames, false dichotomies, and decontextualized clips operate—improve recognition of manipulation in real-world feeds. Cambridge-led experiments conducted on YouTube and subsequent replications demonstrate measurable gains at a low cost per view. However, effects decay over time, which is precisely why time‑boxed election boosters outperform semester‑long generalities. Ministries can push prebunks across school platforms, television, YouTube, and messaging apps, with simple post‑exposure surveys to track sharing intent and belief calibration.

What This Means for Classrooms, Campuses, and Cabinets

For educators, the role is not adjudication of claims, but rather tactical training. Two 15‑minute inoculation segments per week in the month before voting—delivered in the majority language and a local language—can build pattern recognition without politicizing curricula. The evidence base is most substantial for brief, repeated exposures that emphasize manipulation techniques, rather than issue positions. Schools can implement this as part of digital citizenship modules, pairing teacher-led discussions with locally produced pre-bunk videos that mirror the platform's aesthetics, which students already consume. The test is practical: can a student explain how a decontextualized clip or scapegoating frame works before it appears in their feed? That competence, not ideological policing, is the goal.

For universities and research institutes, protocol matters more than heroics. Sign data‑access MOUs modeled on the EU’s DSA guidance, pre‑approve IRB workflows for secure analysis of platform‑provided datasets, and publish weekly risk snapshots during election windows. These snapshots should summarize observed coordination patterns, ad‑library anomalies, and synthetic‑media incidents—without naming individuals—so that public debate has a reliable baseline. The point is to replace scramble mode with predictable routines, where high-risk content triggers measured and transparent responses. Over time, these routines have normalized independent auditing as part of election infrastructure, rather than an act of opposition.

For policymakers, speed should take precedence over elegance. Codify Election Integrity Compacts with public compliance dashboards; enact the 0.02% IPCF with governance insulated from executive influence; and require vendor registries that finally reveal the financial underpinnings of virality. None of this requires censorial ministries. It requires transparency and capacity—the conditions under which publics in the West began denouncing falsehoods because corrective institutions existed to make truth legible and valuable. In settings where journalism’s scrutiny is not yet firmly established, these reforms prevent uninformed audiences from being misled by coordinated swings.

Anticipate the critiques and meet them with design. “Media literacy doesn’t work.” It can—when it is tactic-focused, emotionally engaging, and timed to the risk window. The randomized field experiments support this, and replication studies refine the effect sizes and timing. “Tougher rules invite censorship.” That risk is real, which is why funds must be governed at arm’s length and disclosure duties pinned to campaigns’ supply chains, not to user speech. “Platforms already have election hubs.” Some do; Singapore’s TikTok hub is one example. But without mandated ad‑library fields and guaranteed researcher access, hubs are marketing, not accountability.

The Alignment That Matters: Same Tactics, New Stakes

Across Southeast Asia, the same style of manipulation that warped public discourse in the United States and other advanced democracies is now embedded in electoral life. The difference is not novelty; it is capacity. Where journalism remains undercapitalized and ad transparency is optional, audiences face the firehose without hydrants. The Philippines’ 2025 season—characterized by high public alarm and high-profile platform pressure—shows both the urgency and the limits of ad hoc enforcement. Indonesia’s buzzer markets and creator-driven influence demonstrate how quickly norms can congeal around vibe-based politics when scrutiny is thin. The argument is straightforward and fully aligned with the evidence: in economies and democracies where journalism’s scrutiny isn’t yet structurally secured, the same lie machine hits harder—and it will keep deciding who speaks, who runs, and who rules until the economics of verification are fixed.

Build the Immune System, Not Just Antibodies

Return to the hinge numbers: 67% concern in the Philippines; a world in which journalism is rated “difficult”; core Southeast Asian democracies deep in press‑freedom tables, while short‑form platforms shape attention. The story is not that Southeast Asia has suddenly discovered disinformation; instead, familiar tactics have migrated to contexts where corrections are underfunded and transparency is optional. The remedy is not more content whack‑a‑mole. It is to rebuild the information economy that makes truth durable: time-boxed Election Integrity Compacts that force timely transparency; a modest 0.02% ad-market levy to fund independent newsrooms as infrastructure; campaign-vendor registries that follow the money behind virality; and prebunking that trains pattern recognition just before it’s needed. Do these within two years—before new habits harden—and the region can avoid repeating the West’s long detour. Leave the market for verification unfixed, and the next swing will be larger, faster, and more complex to correct.

The original article was authored by Netina Tan and Aiden McIlvaney. The English version, titled "Bots, buzzers and AI-driven campaigning distort democracy," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights. (2025, May 10). Launch statement: Southeast Asian lawmakers probe violence, dynasties, state resource abuse and disinformation in the 2025 Philippine midterm elections.

Cambridge University. (2022). Social media experiment reveals potential to ‘inoculate’ millions of users against misinformation.

Channel NewsAsia. (2024–2025). AI and deepfakes around recent Southeast Asian elections.

CSIS. (2024). Democracy in the digital age: How buzzer culture is stinging Indonesia’s democracy.

DataReportal. (2025). Digital 2025: Global advertising trends; Global overview; Country snapshots.

European Commission. (2024–2025). DSA election‑risk guidelines; elections toolkit; delegated act on data access for researchers; proceedings against TikTok.

Frontiers in Political Science. (2025). Social media and disinformation for candidates: Evidence in the 2024 Indonesian presidential election.

GMA Integrated News. (2025, May 12). DICT reports faster takedown of election disinformation on Meta platforms.

Inter‑Parliamentary Union. (2025). Sexism, harassment and violence against women in parliaments in the Asia‑Pacific region.

Reuters. (2024, Feb.). Dance moves and deepfakes: Indonesia presidential candidates on TikTok; Generative AI may change elections—Indonesia shows how.

Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. (2025). Digital News Report 2025 (Philippines page; Executive Summary).

RSF. (2025). World Press Freedom Index 2025 global overview; Philippines at 116/180; Indonesia at 127/180; Cambodia at 161/180.

TikTok Newsroom (Singapore). (2025, Apr.). Protecting the integrity of TikTok during the Singapore General Elections.

Yusof Ishak Institute (ISEAS). (2024–2025). Political buzzer networks as a threat to Indonesian democracy; Disinformation and election propaganda

Comment