Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

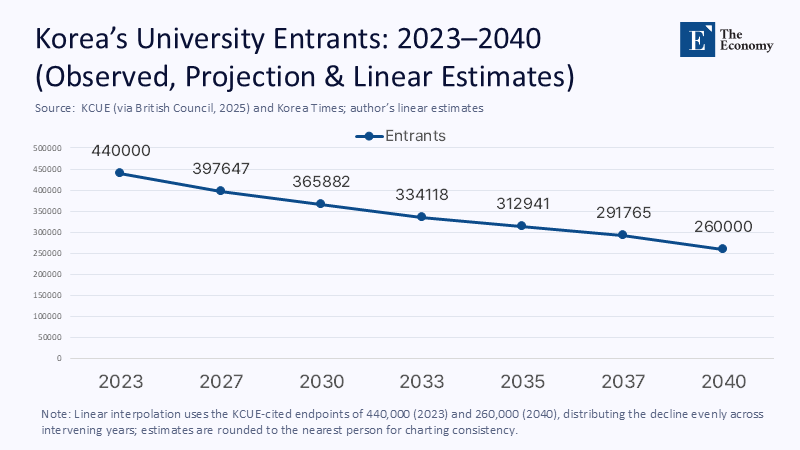

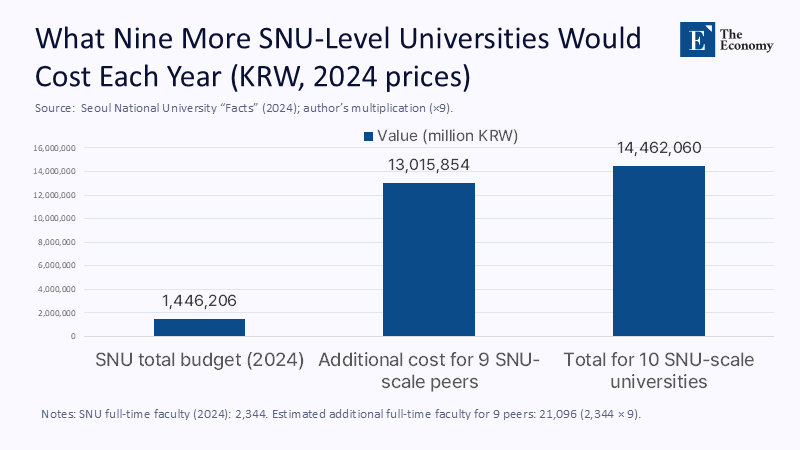

South Korea's fertility rate eked up in 2024 for the first time in nine years—to 0.75 children per woman—yet it remains the lowest in the OECD and far below replacement, meaning every new higher-education plan must be built for a sharply smaller 2030s cohort. Meanwhile, under-enrolment is already here: in the 2024 regular admissions round, 169 universities failed to fill their quotas, leaving over 13,000 seats empty, with regional campuses bearing the brunt; by 2040, the pool of university entrants is projected to shrink from roughly 440,000 in 2023 to about 260,000. Replicating Seoul National University nine times would demand on the order of 20,000 additional research-caliber faculty and an annual budget north of ₩13 trillion if each peer were funded at SNU's level—numbers that collide with the demographic math. No policy can outrun demography, and no branding exercise can conjure an intellectual labor force that does not exist. The arithmetic alone tells us: ten "SNUs" is a mirage.

Prestige Replication vs. System Renovation

The notion that excellence can be decentralized by cloning a flagship misunderstands how research universities work. Top institutions are not mere bundles of buildings and budgets; they are long-accumulated networks of talent density, doctoral programs that reliably place graduates in elite labs, and international ecosystems of collaboration. Korea does not suffer from a shortage of campus logos so much as from a systemic misalignment: a massified system facing a fast-emptying demographic pipeline, concentrated R&D in the business sector rather than universities, and a thin layer of internationally competitive research groups. This 'thin layer of internationally competitive research groups' refers to the limited number of research teams in Korean universities that can compete at a global level. These groups are stretched across too many institutions, making it difficult for them to maintain their competitive edge. A credible path forward reframes the goal from 'replication' to 'renovation': concentrate world-class research capacity in a small number of genuinely global universities and rebuild the rest of the system around differentiated missions—applied research, high-quality teaching, regional innovation, adult upskilling, and international program delivery. That is how other systems turned ambition into outcomes, not by multiplying brand names but by clarifying roles and lifting standards at every tier.

The Demography Doesn't Add Up

Policy must begin with the headcount. Preliminary national data show a modest uptick in births and fertility in 2024 (to 238,300 births and a TFR of 0.75). Still, the recovery is nowhere near the scale required to stabilize university cohorts. Already, universities outside Seoul account for the overwhelming share of shortfalls; in 2024, they made up 61% of the institutions missing quotas, and by early 2025, dozens still had vacancies even after additional recruitment. Sectoral forecasts anticipate a collapse in entrants to roughly 260,000 by 2040, a near-40% decline from 2023. In such a landscape, creating nine more "flagships" would cannibalize students and staff from existing campuses rather than expand capacity. The more plausible demographic strategy is a smaller number of research universities with selective growth in strategically important fields, paired with planned consolidation, shared services, and cross-registration networks. Hence, students in regions access advanced coursework without hollowing out local institutions. Demography is destiny when financing and staffing must follow shrinking cohorts.

A Thin Faculty Pipeline and the Internationalization Gap

Building nine research universities to SNU's scale implies hiring roughly nine times SNU's 2,344 full-time faculty—some 21,000 tenure-track scholars with internationally competitive research portfolios. South Korea does not produce talent at that rate domestically, and its global appeal to senior scholars remains limited. NSF data indicate Korea awards on the order of 8,000 science and engineering doctorates annually (circa 2020), a figure that must also supply government labs and industry R&D. On internationalization, no Korean university ranked within the global top 400 for international faculty in the 2025 QS results, highlighting persistent barriers to recruitment and retention. Nature Index country tables recorded a slight year-over-year decline in Korea's "Share" of high-impact publications in 2024, underscoring that quantity alone is not enough. Even where Korea excels—in overall R&D intensity near 5% of GDP—most R&D is performed and financed by business, not universities, limiting the academic pipeline. Hiring world-class faculty at scale requires more than aspiration; it demands immigration reform, tenure norms aligned to global practice, and competitive packages across institutions.

What the Data Say About Student Readiness

At age 15, Korea's students are excellent by international benchmarks: they scored a mean of 38/60 on PISA 2022's Creative Thinking assessment (OECD average 33), with 46% in the top proficiency bands. Yet this strength coexists with a schooling culture that channels vast sums into private cram schools and rewards exam precision over extended inquiry. Private education spending hit a record in 2024—near ₩29 trillion by press estimates—with almost half of under-six children already in 'hagwon,' signaling the intensity of the pre-tertiary race. This 'pre-tertiary race' refers to the intense competition and pressure students face in the years leading up to their university admissions. The results at the university interface are telling: high non-enrolment among successful applicants at elite universities as students chase medical seats after quota expansions; under-filled regional classes; and an uneven bridge from test excellence to research-ready habits—academic writing, independent design of experiments, persistence through failure. The point is not that students are incapable, but that the pipeline is mis-tuned: PISA-level creativity cannot compensate for admissions systems and curricula that overvalue short-cycle recall and under-reward deep, cumulative learning. Reform should attack the junction between secondary and tertiary education, not multiply campuses.

The Economics of Redundancy

Replicating excellence is expensive. SNU's 2024 budget is about ₩1.446 trillion; nine more peers at comparable scale would imply recurring expenditures above ₩13 trillion per year, before counting capital outlays for facilities, startup packages for labs, and the ongoing costs of global recruitment. In a system already straining to fill seats, that spending would be more efficiently allocated to upgrading doctoral programs, building shared research cores, and purchasing time—less teaching, more protected research months—for existing research-active faculty across a smaller number of designated flagships. University finances will also be squeezed by the flight to medicine after quota expansions: a policy designed for the health workforce that unexpectedly drains top students from science and engineering departments, raising the unit cost of delivering advanced courses with fewer majors. In short, redundancy multiplies fixed costs and dilutes scarce people. Concentration, by contrast, allows investments in global-grade PhD stipends, international co-supervision, and research staff who make labs run at the pace global competition now demands.

A Different Design: Stacked Excellence and Tiered Strength

A better blueprint is "stacked excellence." At the apex, fund two or three national research universities to world-top-20 standards in selected fields within a decade, informed by evidence from Germany's Excellence Strategy and China's Double First-Class policy that focused investment can lift impact—while being mindful of critiques that concentration must be matched with rigorous evaluation and openness to collaboration across institutions. Below that apex, designate a broad tier of applied research universities with industry-embedded master's programs, co-op requirements, and performance-based funding keyed to graduate employment and patents. Elevate teaching-focused institutions through national centers for pedagogy, heavy investment in English-medium and AI-enhanced instruction, and credit-transfer pipelines into apex programs for students who outperform. Complement this with a three-step talent strategy: overhaul PhD training with mandatory international co-advising, fund 1,000 competitive postdoctoral fellowships per year for returning Korean scholars and top foreign PhDs, and redesign visas, tenure clocks, and spousal employment to attract and keep global faculty. This is not symbolic equity; it is system engineering under demographic constraint.

Anticipating the Critiques—and Rebutting Them

Some will argue that without many "flagships," regions will fall further behind. The evidence suggests otherwise. Excellence strategies that couple a small number of apex institutions with networked clusters—shared cores, remote enrollment into advanced seminars, mobile faculty exchanges—can diffuse knowledge faster and more cheaply than building lab-intensive redundancies in every province. Others claim the problem is not structure but prestige; if ten universities share the brand of a capital-city flagship, the pressure on Seoul will ease. Yet prestige does not staff cleanrooms or co-author with Max Planck; people do, and the internationalization indicators show that Korean universities still lag in attracting global faculty at scale. A final critique is that Korea's students are already among the world's best, so capability is not the obstacle. True—and that is precisely why reform should focus on the transition from high school brilliance to undergraduate and graduate depth: bridge years in writing and research methods, capstone-heavy curricula, and admissions that privilege demonstrated inquiry over cram-hardened heuristics. The choice is not between regional equity and excellence; it is between expensive redundancy and sustainable differentiation.

Build Fewer Flagships, Educate More Deeply

Return to the starting figure: a fertility rate of 0.75 and shrinking cohorts that will define higher education for decades. In that world, replicating prestige is a costly diversion; renovating the system is the only responsible policy. Concentrate research at a small apex where global-grade faculty, doctoral funding, and shared infrastructure can cohere. Redesign the middle to be hands-on, industry-linked, and internationally accessible. Strengthen the base so that every prepared student—domestic or international—can climb as far as their stamina and curiosity carry them. Measure progress with complex indicators: international faculty and co-authorship, doctoral placement, share of papers in the top 10% by citations, and graduate employment in frontier sectors. The promise is straightforward: fewer flagships, stronger tiers, better teaching, and surer bridges from school brilliance to scholarly depth. Korea does not need ten new SNUs; it requires the courage to build two or three great ones—and the discipline to make every other institution excellent on its terms.

Methodological note

All figures cited are from 2023–2025 government or international datasets and major outlets. Where exact systemwide costs were unavailable, we estimated by multiplying Seoul National University's reported 2024 budget (₩1.446 trillion) and faculty count (2,344 full-time) by nine to approximate the order-of-magnitude resources required to create nine SNU peers; this produces a conservative annual operating estimate above ₩13 trillion excluding capital costs. Faculty-pipeline feasibility was gauged against NSF estimates of Korea's annual S&E doctoral output and internationalization indicators from QS and Nature Index. Enrollment projections and under-enrollment snapshots were taken from Korean media and sector bodies citing KCUE/KESS and ministry data.

The original article was authored by Kyuseok Kim (KS), the inaugural Center Director for IES Abroad Seoul. The English version, titled "South Korea’s plan to decentralise higher education excellence," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

AP News. (2025, Feb. 26). South Korean births increased last year for the first time in nearly a decade.

British Council. (2025, Feb.). Declining enrolments push Korean universities to merge.

East Asia Forum. (2025, July 29). South Korea's plan to decentralise higher education excellence.

Jeung, Y. (2025, Mar. 14). Ministry allocates funds for fairer university admissions. University World News.

JoongAng Daily. (2024, June 5). Five Korean universities make top 100 of QS World University Rankings.

JoongAng Daily. (2025, June 12). Lee wants 10 SNUs. But can this solve Korea's education crisis?

Korea Herald. (2024, Feb. 26). Universities struggle to fill classes amid population decline.

Korea Herald. (2024, June). Korean unis slide in global ranking.

Korea Herald. (2025, Feb.). Korea's private education sector rakes in profits despite fewer students.

Korea Times. (2025, Jan. 29). Declining enrollments force Korean universities to fight for survival.

Korean Educational Development Institute (KEDI). (2025). KESS Infographics 2024 (Universities, Colleges, Graduate Schools).

Ministry of Education (Republic of Korea). (2024–2025). Education Statistics Overview.

Nature Index. (2024). Leading countries/territories: South Korea.

OECD. (2023–2024). Education at a Glance 2024 – Korea Country Note; Data Explorer.

OECD. (2024). PISA 2022 Results (Volume III): Creative Minds, Creative Schools—Korea Factsheet.

OECD. (2023–2024). Main Science and Technology Indicators (MSTI) Highlights.

Reuters. (2025, Feb. 26). South Korea birthrate rises for first time in nine years, marriages surge.

Seoul National University. (2024–2025). Facts & Budget.

Time Magazine. (2023, Sept. 7). Why the crackdown on private tutoring is a Band-Aid on a larger problem.

University World News. (2024, Feb. 16). Medical school quota rise could shake up higher education.

World News/Financial Times. (2025, Mar. 27). half of under-6s in cram schools; private tutoring at record costs.

Comment