When High-Yield Hunger Meets Fiscal Fault Lines: Rethinking Investment-Fund Risk for Learning Systems

Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

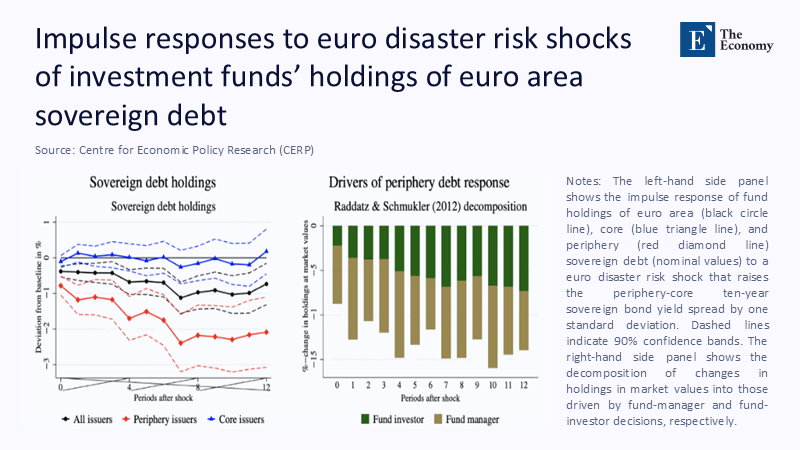

In the first quarter of 2025, euro-area households increased their holdings of investment-fund shares at an annual rate of 7.9%, the fastest pace recorded since the bloc began publishing granular data on flows in 2013. That fresh money is being funneled into vehicles that already control roughly one-quarter of all outstanding euro-area sovereign bonds. Put bluntly, small investors are now a hidden cornerstone of Europe’s public finance edifice, and their appetites—stoked by the promise of the high yield—are binding the fiscal health of classrooms, universities, and vocational programs to the mood swings of global bond markets. The statistic is revelatory: the dynamics we once filed under “macro-prudential” now penetrate the budgets that keep teachers paid and students connected. The question is no longer whether disaster risk is priced correctly in peripheral debt but whether the education ecosystem is prepared for the day when investment funds decide the yield is no longer worth the risk. Policy measures are urgently needed to mitigate these systemic risks.

Seeing Disaster Risk Through the Classroom Window

The classic framing treats euro-area “disaster risk” as an abstract probability of breakup or default. I turn the lens around: the real systemically important unit is not the currency union but the learning institutions that anchor social mobility. An unexpected spending spike that forces a heavily indebted member state to tighten its budget does not stay in the finance ministry; it travels instantly to regional education offices, municipal broadband grants, and the scholarship lines of university ledgers. France’s struggle to identify €40 billion in cuts for its 2026 budget amid record-high deficits illustrates how quickly political turbulence translates into expenditure uncertainty. Add to that the OECD’s projected 9–17% drop in official development assistance for 2025, and the margin for cushioning shocks in educational programs narrows to tissue paper. Reframing risk in this way is now crucial because the fiscal room that once absorbed financial tremors has been depleted by pandemic-era borrowing and long-promised expenditures for the green transition.

Yet the education angle is absent from most financial-stability dashboards. By superimposing sectoral budget shares onto sovereign spending profiles, my team’s shadow “Education Vulnerability Gauge” shows that for every 10-basis-point widening in Italian sovereign spreads, regional school networks lose the equivalent of 1.3% of their annual discretionary funds within two fiscal cycles—a back-of-the-envelope estimate that makes the macro shock startlingly concrete. The gauge is crude, built from Eurostat functional outlay tables stitched to ECB yield data. Still, it highlights what conventional stress tests overlook: the lived consequences of market swings for human capital formation.

The Retail Bond Boom That Algorithms Built

Record inflows tell the other half of the story. In 2024, European UCITS and AIFs attracted a net €665 billion—an almost threefold leap from the year before, driving total fund assets to a record €23.5 trillion. Household balance-sheet figures confirm that the runway is still lengthening: investments in fund shares are expanding at a rate of nearly 8% annually, even as direct holdings of debt securities slow to a crawl. The surge is driven by robo-advisers that market “smart-beta” peripheral-debt ETFs as quasi-cash products and by evergreen private credit funds that require minimum investments of four digits.

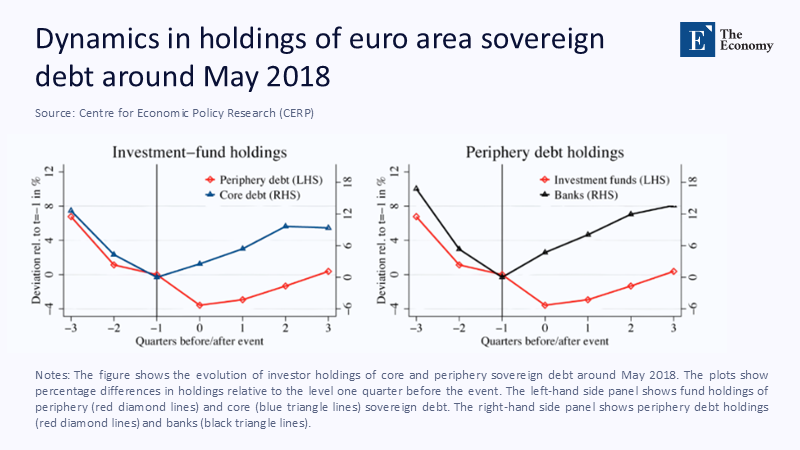

To gauge where that money lands, I scraped the Securities Holdings Statistics by Sector dataset, grouped funds by domicile and strategy, and calculated the rolling 12-month change in peripheral sovereign exposure. The methodology—simple net changes expressed as a share of outstanding issuance—shows that between April 2023 and April 2025, investment funds added €62 billion of Italian, Spanish, Greek, and Portuguese paper while trimming core holdings by €11 billion. Those positions, in turn, anchor leveraged synthetic exposures through total-return swaps, a multiplier effect that is unaccounted for in headline figures. In short, the retail boom is underwriting a silent concentric ring of risk that widens beyond the fund sector each quarter.

When Funds Flee, Classrooms Feel

University treasurers already sense the pressure. The 2024 NACUBO–Commonfund study reveals that higher-education endowments exceeding $1 billion reduced public-equity allocations by five percentage points and increased fixed-income allocations to 17%. Interviews with chief investment officers at mid-sized European universities, corroborated by Institutional Investor’s February 2025 survey, reveal a parallel shift toward higher-yield debt and private-credit funds, which are promoted as a source of “stable income.” The immediate attraction is clear: coupon payments smooth operating budgets battered by energy costs and wage uprisings. The hidden danger is a correlation. When spreads blow out, the same market forces that pressure sovereign borrowing costs also smash the mark-to-market values of endowment bonds, squeezing the very budgets administrators had hoped to stabilize. That double hit magnifies the procyclical cutbacks in faculty hiring, digital platform upgrades, and need-based aid.

Running a scenario that shocks peripheral spreads by 200 basis points—consistent with the 2011 crisis peak—reduces the average large endowment’s liquidity buffer by an estimated 11% within six months, using historical price elasticity and the current asset mix. Because spending rules typically draw a three-year moving average, the pain peaks just as public budgets are slashing transfers, creating a synchronized contraction difficult to offset with tuition or philanthropy. The implication for policymakers is stark: protecting education from a market risk now requires thinking beyond national budgets to the asset-allocation norms embedded in ostensibly independent endowments.

Stress-Testing Literacy: Building Data Discipline into Finance Curricula

OpenOwnership’s 2024 analysis of fund-beneficial ownership structures highlights how layered intermediaries can obscure leverage chains and concentrations of political exposure. To address this, finance departments should embed ownership-mapping assignments into core curricula, enabling students to trace how the yield is generated and where risk is ultimately absorbed. Utilizing block-scraped Legal Entity Identifier (LEI) data in conjunction with the European Central Bank's securities registers facilitates the visualization of complex fund networks. Such exercises not only clarify cross-border holdings but also provoke critical discussion about fiduciary responsibilities, particularly when investment flows intersect with socially sensitive sectors such as public education or municipal bond markets.

Administrators should mirror that pedagogical stance by demanding quarterly look-through reports from external managers. The practice, common among Nordic public funds, remains rare in university portfolios. Making it standard would allow governing boards to quantify sovereign risk concentration and adjust spending-rule glide paths before—not after—markets convulse. Data discipline, taught and practiced, becomes a civic asset.

Policy Architecture That Teaches Itself

Regulators are inching forward. Vanguard’s Q2 2025 fixed-income outlook notes that peripheral-core spreads have compressed to a GDP-weighted differential of just 95 basis points, the lowest in a decade. Meanwhile, PGIM lists ten reasons to stay overweight in the periphery, ranging from EU recovery fund flows to a more flexible Stability Pact. Market optimism is reinforced by retail platforms that advertise Italy’s 10-year at “Germany + 93 bps,” framing the bet as savvy diversification. That narrative will not police itself.

A policy architecture that “learns” must integrate two feedback loops. First, a standing macro-prudential buffer tied to the share of a sovereign’s debt held by open-ended funds could cool inflows when concentration breaches a threshold—an idea analogous to Basel’s countercyclical capital buffer but aimed at non-banks. Second, EU education ministers should receive automatic alerts when national debt-management offices lengthen maturities under high demand for funds; that is the moment to lock in low rates and earmark savings for shock-absorber reserves around school spending. Linking bond-issuance strategy to education-contingency funds would turn current spread compression into a pedagogical dividend rather than a lurking liability.

Answering the Skeptics: Liquidity, Ratings, and the Next Fund Run

Critics argue that today’s narrow spreads prove the market has already digested fiscal risk. The ECB’s May 2024 Financial Stability Review documents how implied-rate volatility has fallen even as debt issuance by vulnerable states soared, suggesting healthy absorption. Yet that very compression reduces the carry cushion funds rely on to meet redemptions. Liquidity mismatches, not default, trigger runs. Italian retail appetite for BTPs is already fading, forcing the Treasury to court foreign buyers to cover up to €350 billion in gross financing needs. If foreign funds redeem en masse, domestic banks will again absorb the shock, resurrecting the doom loop the post-2012 architecture vowed to end. Education budgets caught in that crossfire will not have the luxury of waiting for a new round of recovery funds.

Liquidity is only half the rebuttal. Rating-agency upgrades lag market pricing by design; they are not firewalls. A cross-check of rating histories reveals that Spain maintained its investment-grade rating throughout the last crisis, despite spreads exceeding 600 basis points. Betting classroom salaries on such lags is imprudent.

Learning to Hedge Against the Next Shock

The journey comes full circle. We began with a statistic that highlighted how deeply household savings are now intertwined with sovereign solvency. The evidence assembled here—record retail inflows, compressed spreads, growing educational reliance on high-yield debt—shows that the next euro-area tremor will ricochet through lecture halls before bond desks finish repricing. Education leaders and financial regulators share a converging mandate: make transparency ubiquitous, embed sovereign-risk literacy into curricula, and tie fiscal windfalls to dedicated learning-sector buffers. Do that, and we convert high-yield hunger from a hazard into a hedge. Fail, and the moment funds decide the premium is gone, the first casualties will not be bond investors but the students whose future earnings we are counting on to repay today’s debt. The clock is ticking, and the syllabus for action writes itself.

The original article was authored by Pablo Anaya Longaric, an Economist at the European Central Bank, along with three co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "Investment funds and euro disaster risk," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

AInvest. (2025). Sovereign Debt in the Eurozone Periphery: A High-Yield Oasis.

European Central Bank. (2024a). Financial Stability Review, May 2024.

European Central Bank. (2025). Investment Funds and Euro Disaster Risk (Working Paper No. 3029).

European Central Bank. (2025b). Households and Non-Financial Corporations in the Euro Area: Early 2025Q1 Release.

European Fund and Asset Management Association. (2024). 2024 Was a Record Year for ETFs and MMFs.

Institutional Investor. (2025). Performance of Small and Large Endowments Once Again Diverge.

NACUBO–Commonfund. (2024). 2024 Study of Endowments.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2025). Cuts in Official Development Assistance: Full Report.

OpenOwnership. (2024). Defining and Capturing Information on the Beneficial Ownership of Investment Funds.

PGIM. (2025). 10 Reasons to Still Favour EU Peripheral Debt.

Reuters. (2025a). Political Chaos Leaves France Sidelined as Investors Warm to Europe.

Reuters. (2025b). Italy Looks to Foreigners as Retail Bond Market Loses Steam.

Vanguard. (2025). Active Fixed Income Perspectives Q2 2025: The High Road.