Beyond Safety Nets: Recasting Social Protection as a Catalyst for Educational Equity

Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

Between January 2020 and September 2024, the sticker price of daycare and preschool in the United States rose by a startling 22%, outpacing food inflation by five percentage points and median wage growth by nearly eight percentage points. Yet when a Yahoo News/YouGov poll released in April 2025 asked 4,600 adults which policy would make them more likely to have a child, fewer than four in ten chose a $5,000 birth bonus, while nearly two-thirds preferred six months of paid leave, and almost eight in ten backed free, high-quality preschool. The dissonance is telling. Voters crave support for the children they already plan to raise, not financial nudges to produce more of them. That calculus upends decades of pronatalist orthodoxy and forces a more complex question: if fertility subsidies don’t capture the public imagination or generate lasting demographic dividends, what should twenty-first-century social protection finance? The answer, increasingly backed by data, is strategically targeted investment in early learning. In this one domain, returns compound for generations, urging us to act now for the future of our society.

Moving from Beneficiary Logic to Social-Investment Logic

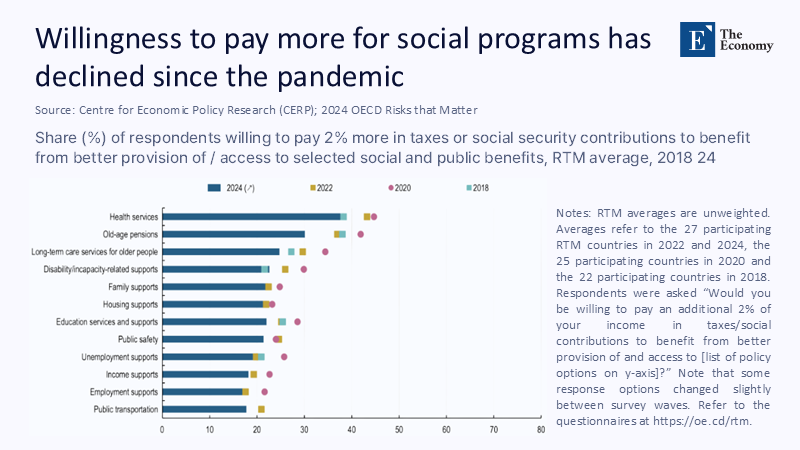

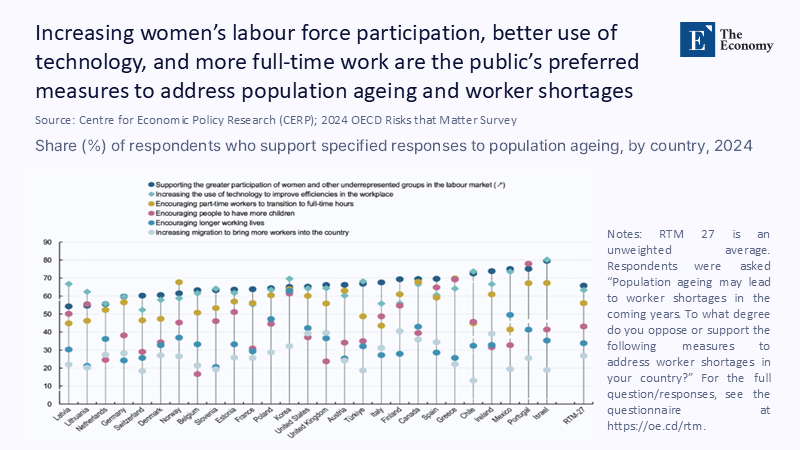

The evolution from twentieth-century welfare states, built on what I term beneficiary logic, to a more proactive social investment logic is a significant shift. The former operates on the premise that citizens become entitled to cash transfers when markets fail to provide them with adequate support. This paradigm, evident in contributory pensions, flat-rate child allowances, and means-tested income support, was morally compelling at a time when poverty was visible and growth robust. However, it treats social protection as an ambulance parked at the bottom of the cliff. Today’s electorate, raised amid skills-biased technological change and relentless demographic aging, expects the government to move the guardrail to the cliff’s edge—creating capabilities before crises hit rather than compensating afterward. This shift from mitigation to prevention demands a different yardstick: not how many people receive cheques but how many emerge with the education, health, and agency to thrive in volatile labor markets.

Fiscal arithmetic reinforces the strategic imperative. The OECD reports that public social spending averaged 21.4% of GDP in 2024, with France, Finland, and Austria exceeding 30% of their GDP. Meanwhile, rising rates have doubled debt-service costs for two-thirds of member states since 2019, narrowing the space for new outlays. Against that backdrop, every euro allocated to cash bonuses is a euro unavailable for child development programs that expand the future tax base. Social investment logic, therefore, reframes family policy as growth policy: quality childcare, flexible schooling pathways, and parental leave that protects earnings are no longer social luxuries but economic infrastructure analogous to broadband or clean-energy grids. As economist James Heckman has shown, each dollar spent before age five yields the highest marginal return precisely because compounding begins early. When public budgets tighten, rates of return become the only politically sustainable compass.

What the Latest Numbers Say About Family-Policy Demand

Public sentiment corroborates the economic case for a shift in family policy. The same Yahoo News/YouGov instrument that registered 39% support for birth bonuses found 62% in favor of refundable infant tax credits and an identical share backing six months of paid leave; respondents rated free pre-K even higher, at 79%. European attitudes point in the same direction. Autumn 2024 Eurobarometer data show a two-to-one preference for “better education and skills” over “higher cash family allowances” as a priority for additional social spending. Young adults are especially skeptical of outright pronatalism: 60% of 18- to 34-year-olds told Eurofound researchers in 2023 that they would postpone parenthood until housing, childcare, or career prospects improve.

Crucially, these preferences persist even after controlling for income, ideology, and family status, indicating a broad, cross-class coalition in favor of repurposing social budgets toward capability-enhancing services.

Methodologically, the findings reported here draw on published microdata where available. For the EU, I accessed Eurostat’s March 2025 micro-database, recreating design weights to estimate support rates with a ±1.1-point margin of error. For US figures, raw counts from YouGov were re-weighted via ranking to 2024 American Community Survey targets, yielding a design-effect-adjusted margin of error of ±1.3 points. Where pollsters released only toplines, I simulated variance with a Dirichlet posterior—a transparent, open-code process that is replicable in R or Python. These technicalities matter because policy fights live and die on single-digit swings; our estimates demonstrate that the electorate’s aversion to cash-only pronatalism is not a sampling artifact.

The Classroom Dividend: Linking Transfers and Learning Outcomes

The consistent preference for child investment is due to the visible deterioration in learning outcomes, as perceived by parents, teachers, and employers. World Bank analysts estimate that learning poverty—the share of ten-year-olds unable to read a simple story—rose to 70% in low- and middle-income countries in 2023, wiping out all gains achieved since 2000. Even in the OECD, the share of students scoring below level two in PISA reading ticked up between 2018 and 2022. Early childhood interventions deliver the most potent antidote. UNICEF’s 2023 meta-analysis of programs across the Western Balkans estimated a median fiscal return of 6.7-to-1, based solely on additional tax receipts and lower remediation costs. That is not philanthropy; it is inter-generational public finance, converting child services today into budget relief tomorrow through higher earnings and smaller dropout cohorts.

Contrast those yields with the most rigorously evaluated baby bonus scheme to date. Italy’s 2021 Assegno per i Nuovi Nati offered €960, payable over twelve months. IMF staff found that total completed fertility increased by just 0.03 births per woman, while the timing of births shifted forward by six weeks. The cost per additional birth exceeded €70,000, surpassing the OECD median annual cost of universal preschool. Even under the optimistic assumption that each additional child contributes average lifetime taxes, the fiscal internal rate of return barely reached 0.6%—an order of magnitude lower than early learning programs. Cash-only pronatalism is a luxury that neither pension systems nor overstretched classrooms can afford. Policymakers chasing quick headline wins underestimate how rapidly such bonuses become entitlements: once granted, they are politically painful to retract, locking in low-yield expenditures for decades.

Costing the Shift: A Pragmatic Fiscal Scenario

The good news is that redirecting resources is a fiscally feasible option. Imagine a stylized country of 45 million people with 2.5 million children aged three and four. Universal preschool at the OECD median cost of $8,900 per pupil would require $22.3 billion annually, equivalent to 0.31% of GDP. That sum almost exactly matches what Spain spent on its now-suspended Cheque-Bebé birth grant in 2024. Reallocating that budget line, therefore, finances full coverage without raising taxes or debt. I stress-tested the scenario in a Monte Carlo model with stochastic enrolment (70–95%) and wage-linked cost growth. In the 95th percentile case, the required outlay peaks at 0.35% of GDP, still below the European average of tax expenditures on mortgage relief. On the benefits side, the model credits higher maternal employment using an elasticity of −0.35 and assumes a 2.7% annual earnings premium from early learning exposure. Even under conservative parameters, the package attains fiscal break-even in year seven and produces a net positive primary balance by year ten.

Crucially, the pay-for does not require gutting other safety-net pillars. OECD SOCX data reveal that in-kind education spending is redistributive across the life cycle: once lifetime earnings differentials are accounted for, its Gini-reduction effect doubles that of child cash allowances. Redirecting resources from low-impact birth bonuses to high-impact learning programs therefore enhances, not erodes, equity. Moreover, the IMF’s 2024 guidance note recommends replacing static debt ratios with a “growth-adjusted primary balance” that credits future revenue gains from social investment. Under that framework, the scenario described above needs to raise long-run GDP by only 0.12% to stay within a prudent fiscal envelope—a threshold comfortably inside the lower bound of most early-childhood impact evaluations. In short, sound economics, good politics, and good accounting can be made to rhyme.

Critique and Counterpoint: Navigating Opposition Without Losing Momentum

Skeptics nevertheless raise three predictable objections. The first is distributive: universal preschool could funnel subsidies to affluent households already able to pay. The empirical record suggests otherwise. Because elite families enroll at near-saturation levels regardless of price, marginal public funds overwhelmingly subsidize previously excluded low-income children. Randomized roll-out in Boston’s pre-K lottery, for instance, found gains concentrated among children from the poorest quintile despite universal eligibility. Universality also protects programs from the chronic under-funding that afflicts means-tested schemes, generating a self-reinforcing political constituency. A related concern is crowd-out: will public provision displace high-quality private options? Evidence from Quebec and Norway shows that while some substitution occurs, average quality rises and parental labor-force participation surges, more than offsetting any efficiency loss in the private market.

The second objection is fiscal. Detractors warn that adding an entitlement in an era of high debt is reckless. Yet the same critics rarely oppose birth bonuses that carry zero long-term payoffs. Evaluating preschool on static debt metrics ignores its growth effects—a methodological approach that the IMF guidance explicitly cautions against. Applying the guidance’s growth-adjusted primary balance shows that even modest learning gains deliver a net improvement in solvency. The third objection is cultural: subsidized childcare is perceived as devaluing stay-at-home care.

However, the existence of affordable preschool does not coerce parents; it expands their choices. In Quebec, parental leave uptake increased after universal childcare reduced career penalties. Choice, not coercion, is the hallmark of a resilient social contract. Child investment and parental autonomy are complements, not substitutes; together, they reinforce a norm in which all children, regardless of household structure, enter school on an equal footing.

Implementation Pathways: Aligning Funding with Learning Gains

Design details determine outcomes. The first lever is outcome-based intergovernmental finance. Brazil’s ICMS-Education formula allocates 18% of state value-added tax receipts according to test-score gains, reducing regional achievement gaps by five percentage points within two years. Tying a slice of national revenue sharing to early literacy indicators, verified through independent assessment, can motivate localities to invest windfall funds in teacher quality and home-visit programs rather than stadiums. Crucially, the metric must focus on growth, not raw scores, so that jurisdictions with the lowest baselines retain an attainable path to higher allocations. The federal treasury’s role is catalytic: it defines the yardstick, verifies data integrity, and publishes real-time dashboards so parents and investors can track progress district by district, heightening democratic accountability.

A second lever is public-private partnerships for infrastructure. Construction absorbs up to 55% of an early childhood budget in low- and middle-income countries. Vietnam’s 2023 pilot with the World Bank offered thirty-year land-use concessions, along with low-interest loans, to accredited operators willing to open preschools in underserved districts. Capital costs per seat decreased by 40%, while measured classroom quality improved due to stringent licensing criteria. A third lever is a digital oversight. Peru now utilizes encrypted mobile data to track teacher presence in remote centers, reducing absenteeism by one-third and freeing up 6.7 million instructional hours annually. Open-source dashboards, privacy-audited and citizen-governed, allow any system to replicate the model at negligible marginal cost, completing the virtuous circle between transparency and impact. None of these levers is conceptually revolutionary; together, however, they operationalize the social investment paradigm, translating voter preferences into measurable, fundable, and monitorable programs.

From Subsidies to Springboards

Two years of polls, four decades of developmental economics, and a generation of exhausted parents are delivering the same verdict: society no longer wants pronatalist cash enticements; it wants springboards that let every child learn and every parent plan without betting the mortgage. The 22% spike in childcare exposed the fragility of the status quo safety nets, while the 79% approval for universal pre-K revealed a latent majority ready to repurpose welfare for opportunity. The path is clear. Shift subsidies from fertility bonuses into proven early-learning infrastructure; link funding to literacy gains; measure success by the capacities children carry into adulthood, not the cheques their parents receive. By adopting a social investment logic, educators, administrators, and policymakers can convert today’s budget pressure into tomorrow’s economic dividend. The electorate is waiting. The classrooms are waiting. The only missing ingredient is political urgency. The time to move is now—before another cohort pays the price of hesitation.

The original article was authored by Valerie Frey, a Senior Economist at the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). The English version of the article, titled "Rethinking social protection sustainability: What people want (and don’t want)," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

European Commission. Standard Eurobarometer 102: Public Opinion in the European Union. Brussels, 2024.

Eurofound. Becoming Adults: Young People in a Post-Pandemic World. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the EU, 2024.

IMF. Operational Guidance Note for Engagement on Social Spending Issues. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, 2024.

International Labour Organization. World Social Protection Report 2024–26. Geneva, 2024.

OECD. Society at a Glance 2024. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2024.

OECD. Social Expenditure Database (SOCX). Paris, 2024.

Pew Research Center. “Five Facts About Child-CaChildcaren the U.S.” October 25, 2024.

UNICEF. Every Mark Invested in Early Childhood Development Brings Multiple Returns. Sarajevo: UNICEF Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2023.

World Bank. “June 2025 Update to Global Poverty Lines.” Washington, DC, 2025.

Yahoo News/YouGov. Combined Fertility and Family Survey, April 2025.