Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

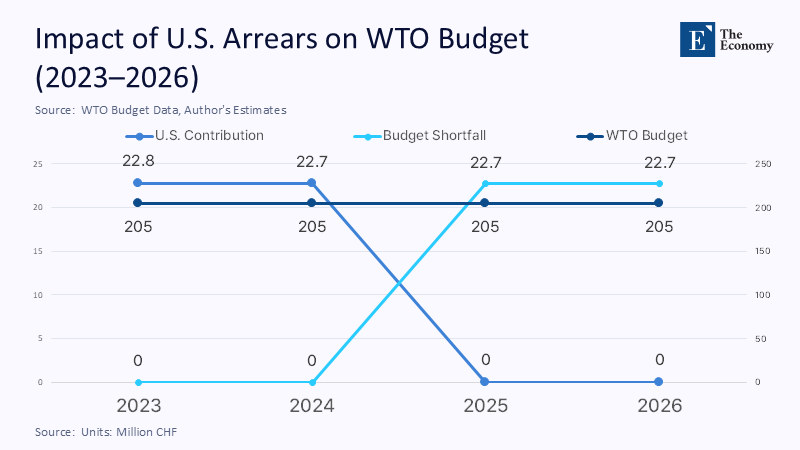

The day the United States skipped a 22.7-million-franc payment to the World Trade Organization was not accompanied by fireworks or fiery speeches. Yet, it carried the quiet force of a constitutional amendment: with one missed transfer, Washington effectively rewrote the assumptions on which the global trading order—and every classroom explainer of it—has rested for three decades. Behind that bookkeeping lapse lies an unpopular but increasingly incontestable proposition: the United States is not preparing for a clean, theatrical exit from the WTO; it is already halfway out the door, dismantling the institution piecemeal through arrears, procedural vetoes, and the creation of parallel venues. The decline is less a revolt than a prolonged indifference, but the consequences for policy architects, educators, and supply-chain managers are as disruptive as any tariff war. Educators must adapt their curricula to this changing landscape. What follows is a forensic reconstruction of that slow-motion divorce, the numerical evidence of its global spillovers, and the curricular shockwave it is sending through schools that teach the next generation of trade diplomats.

The Quiet Fiscal Seismograph in Geneva

Inside the WTO budget committee, the United States’ assessment has long served as a fiscal seismograph: when the most significant donor pays on time, the organization’s modest CHF 205 million budget feels unshakeable; when it does not, every line item quivers. By March 2025, Washington had slipped into “Category 1 arrears”, forfeiting its ability to chair committees and forcing Director-General Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala to freeze new hires, defer training missions, and canvass member states for emergency contributions. The withheld CHF 22.7 million represents 11% of the core budget. If the arrears persist through the next biennium, foregone interest and co-financing could reduce the WTO’s operational capacity by CHF 75 million—enough to eliminate every technical assistance workshop delivered to least-developed members in 2024. Such cuts land hardest on countries where customs revenue funds basic public services, turning a Washington budget wrinkle into a Port-au-Prince classroom crisis.

Legislating Silence: Capitol Hill’s Non-Debate

On paper, Congress is debating withdrawal. In reality, it is barely whispering about it. House Joint Resolution 93, introduced this spring, asks Congress to revoke its 1994 consent to the Marrakesh Agreement in a mere 142 words—shorter than most restaurant disclaimers. Representative Tom Tiffany’s companion bill repeats the demand in language so spare it reads like a sticky note pasted to the Capitol dome. Hearings remain perfunctory; the once-routine testimony from multinational manufacturers in defense of WTO disciplines has dried up. The Republican leadership, preoccupied with tariffs as instruments of industrial policy and culture-war signaling, treats multilateral norms as a legacy concern. Democrats, while more rhetorically supportive, have not marshaled the votes or the airtime to contest the slide. The non-debate is instructive: in the world’s most powerful legislature, the choice between rules-based commerce and ad-hoc deal-making no longer holds sway.

Budgetary Gravity and Systemic Ripples

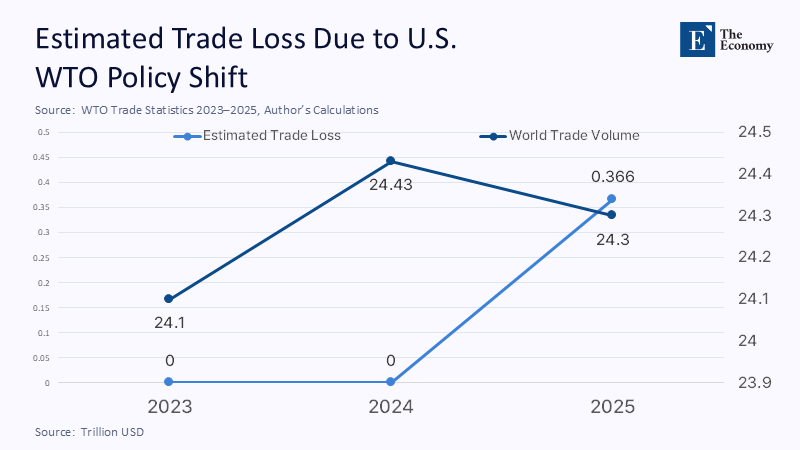

The arithmetic behind that political torpor is stark. According to the WTO’s 2025 “Global Trade Outlook,” merchandise exports reached US$24.43 trillion last year. US goods exports totaled roughly US$3.2 trillion—about 13% of the total—giving Washington an outsized capacity to influence aggregate demand when it adjusts tariff schedules or imposes retaliatory duties. WTO economists calculate that the current array of reciprocal surcharges—averaging ten percentage points on affected lines—could reduce 2025 world merchandise trade volumes.

By 1.5%, that ratio to the 2024 trade base, and the contraction approaches US$ 366 billion—fifteen times the WTO’s annual budget. In other words, every franc the United States withholds from Geneva multiplies into hundreds of lost dollars in cross-border commerce, a cost-benefit mismatch that would bewilder any first-year finance student were it not obscured by political theater.

An Apex Court in Abeyance

Fiscal withholding is only the visible part of the glacier. The deeper fissure runs through the dispute-settlement system, where the Appellate Body—the equivalent of the Supreme Court of Trade Law—has been without a quorum since December 2019. Despite eighty-seven formal attempts by WTO members to fill the vacancies, Washington continues to block consensus renewals, arguing the Body exceeded its mandate. Into that vacuum has stepped the Multi-Party Interim Appeal Arbitration Arrangement, or MPIA, which now counts fifty-six economies after the United Kingdom’s accession in June 2025. The MPIA salvages appellate review for its signatories but simultaneously codifies a two-track justice system inside the WTO: one with enforceable appeals for those willing to opt in and another—effectively an honor system—for disputes involving the United States.

The pedagogical headache is immediate. A trade-law syllabus that once traced a neat panel-appeal-implementation timeline must now chart branch points: a US-China steel case enters an appellate cul-de-sac, an EU-Brazil sugar fight proceeds to MPIA arbitration, while an intra-African dispute circumvents both by mutual agreement. The result is less a rules-based order than a pick-your-own-venue bazaar. For scholars who once praised the WTO as the safeguard against power politics, the new map resembles the patchwork of 1930s bilateral clearing arrangements—a haunting historical rhyme.

From Rules to Deals: The Macroeconomic Price of Fragmentation

What does that fragmentation cost? The WTO Secretariat warns that a bifurcation of trade into rival blocs could lower long-term global GDP by 5%; the International Monetary Fund places the upper bound at 7%, comparable to erasing the Japanese economy every year. Reuters analysis of the WTO’s April forecast underscores the near-term damage: trade volumes, already tepid, are projected to contract 0.2% in 2025, a downgrade primarily driven by US tariff escalations. That negative swing, though decimal-small, translates into tens of billions in forgone customs revenue for developing countries and squeezes the fiscal space for social spending, including education, the very sector most dependent on predictable growth.

Companies are not waiting for a formal US exit to recalibrate. Freight-forwarder hedges indicate that a 25-basis-point rise in the “trade-policy uncertainty index” results in a roughly 1% increase in landed costs, offsetting two years of gains from logistics automation. Multinationals now model a “Geneva discount factor” alongside exchange-rate scenarios, effectively taxing themselves for the political risk of an inactive dispute court. If the WTO once socialized commercial risk, its partial paralysis has privatized it—exporters and importers absorb the variance in everything from transit insurance premiums to inventory buffers.

Teaching Trade After the Consensus

In lecture halls, the shift is palpable. Where professors once opened with Article I—the most-favored-nation clause—many now begin with a crisis module, challenging students to design contingency frameworks for a world in which the guardian of non-discrimination is on life support. One graduate seminar at Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service requires teams to draft mock corporate bylaws specifying how a firm would respond if the United States were to withdraw from the WTO formally. Another simulation at the University of Geneva involves a ministerial conference in which delegates must renegotiate the agreement establishing the organization, but with weighted voting to circumvent US objections. These pedagogical innovations aim not to lament the WTO’s retreat but to cultivate negotiators capable of rebuilding plural-lateral coalitions when hegemonic commitment collapses.

Scenarios for a Post-American WTO

Policy think tanks are gaming three broad trajectories for the next three years. The first is institutional atrophy: Washington continues to pay nothing, blocks all Appellate Body appointments, and marginalizes the WTO in favor of bilateral “Trump deals .”Under that scenario, the MPIA enlarges to seventy members, effectively becoming a shadow appellate system. The second is coercive reform, in which the remaining major economies—namely, the EU, China, India, and Brazil—tie budget votes to weighted contribution rights, thereby diluting US veto power. Legally feasible under Article IX:1, the move would provoke American backlash but could unlock overdue procedural modernization. The third is conditional re-engagement under a future US administration if new concessions—on e-commerce, industrial subsidies, or global carbon fees—make the WTO politically viable again. Each scenario carries different pedagogical implications, yet all share one constant: the organization’s survival will hinge less on diplomatic bromides than on the crunch of numbers—budget shares, tariff elasticities, and the cost of uncertainty priced by markets.

The Moral Hazard of Waiting for 2029

Much commentary clings to 2029—the year after America’s next presidential term ends—as a redemptive horizon, assuming a different occupant of the Oval Office might resume cheque-writing and unblock judges. That presumption misunderstands path dependence. By then, graduating MBAs will have coded workaround clauses into contracts, customs authorities will have digitized alternative arbitration portals, and mid-size states will have normalized the MPIA for most disputes. Once those operating systems are entrenched, American re-entry would require not just a change of heart but concurrent retrofitting across thousands of agreements. Waiting, therefore, invites a perverse moral hazard: the longer the US withholds engagement, the more its exporters invest in coping strategies that lower their future interest in institutional revival. At a certain threshold, the cost of coming back outweighs the perceived benefits, rendering disengagement sticky.

Calculating the Cost of Indifference

The slow fade of the United States from the WTO is easy to miss precisely because it lacks the drama commentators crave. There is no walk-out, no snapped gavel, only balance sheets unbalanced, and meeting rooms half-empty. Yet the magnitude of the loss—quantifiable in budget shortfalls, trade volume contractions, and foregone jurisprudence—renders the episode one of the most consequential institutional unwindings since the dissolution of the League of Nations. For educators, the moment is doubly salient: it demands an overhaul of syllabi and an explicit reckoning with the fragility of the rule-based order we once taught as settled fact. For policymakers, the numbers offer a brutal clarity: starving Geneva of CHF 22.7 million imperils commerce worth several hundred billion dollars and invites a multi-trillion-dollar GDP haircut if fragmentation deepens. Indifference, in short, carries a sticker price, and the invoice is being mailed not to negotiators but to citizens whose livelihoods rely on predictable borders. Whether the United States ultimately signs that cheque will define the next chapter of globalization—and the case studies our students will inherit.

The original article was authored by Henrik Horn and Petros C. Mavroidis. The English version of the article, titled "Why the US and the WTO should part ways," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Congressional Record. H.J.Res. 93, 119th Congress (2025–2026) Withdrawing approval of the agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization.

CSIS. “The World Trade Organization: The Appellate Body Crisis,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, accessed 24 June 2025.

France 24. “US ‘in arrears’ at the WTO,” 28 March 2025.

International Monetary Fund. Gopinath, G., remarks on economic fragmentation, Medellín, 11 December 2023, Reuters synopsis.

Reuters. “UK joins WTO trade arbitration alternative,” 25 June 2025.

Reuters. “US suspends financial contributions to WTO, trade sources say,” 27 March 2025.

Reuters. “WTO aims to reduce staffing costs after US funding pause,” 8 April 2025.

Reuters. “WTO slashes 2025 trade growth forecast, warns of deeper slump,” 16 April 2025.

Tiffany, T. Press release introducing the World Trade Organization Withdrawal Measure, 10 April 2025.

WTO Blog. “Over 80 percent of global merchandise trade is on MFN basis,” 21 January 2025.

WTO. “Global Trade Outlook and Statistics 2025,” April 2025 edition.

WTO. “News Release: Trade forecast April 16 2025,” WTO Press.

WTO. Speech by Director-General Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, Per Jacobsson Lecture, 2 October 2024.

WTO Statistics Portal. “World Trade Statistics 2024,” accessed 24 June 2025.

WTO. United States—Member information (exports data), accessed 23 June 2025.