When Size Shapes the Tax: Rethinking VAT for Unequal Growth and the Reassurance of Digital Compliance

Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

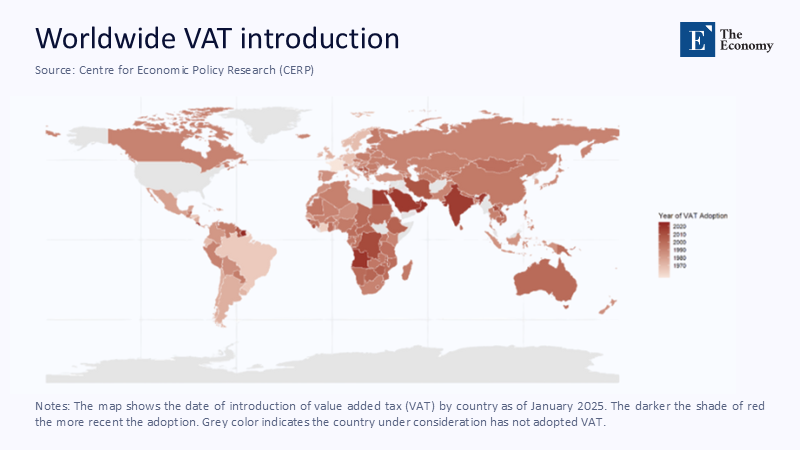

In 2024, European treasuries watched €89.3 billion in potential value-added tax (VAT) revenue disappear—enough to waive tuition at every public university on the continent for an entire academic year, to fund the whole Erasmus+ exchange program twice over, and still leave €12 billion unclaimed. Shift the lens to Asia, and the picture flips: China’s harmonized VAT now covers its entire annual sovereign-debt interest bill, while Japan’s 2019 rate hike finances one-fifth of national pension outlay. How can the same tax be so effective in one region yet ineffective in another? Scale is the hinge. Where domestic demand dominates, VAT thrives; where exports rule, it starves. Unless export-driven economies redesign their consumption taxes, the next decade will see widening fiscal holes patched by deeper cuts to education and harsher levies on those least able to pay.

A Billion-Euro Blind Spot

In 2024, European treasuries watched €89.3 billion in potential value-added tax (VAT) revenue evaporate through compliance gaps—enough to keep every public university on the continent tuition-free for an academic year or to fund the Erasmus+ mobility scheme for almost two additional years. That staggering leakage coexists with another reality: seven consumption-powered giants—China, India, Germany, France, Japan, the United Kingdom, and Brazil—now rely on VAT for roughly one-quarter to one-third of all government revenue, cushioning budgets against slowing corporate profits and aging workforces. The coexistence of windfall and waste defines what many scholars have dubbed the “VAT paradox.” Look closer, and a missing variable emerges: economic scale. Where domestic demand dominates, VAT thrives; where exports rule, it starves. The following essay argues that market size—not commodity dependence alone—determines whether VAT nourishes or undermines public services, and it explains why, without reform, export-driven states risk entrenching fiscal fragility and widening inequality.

Reframing the VAT Debate Through the Lens of Scale

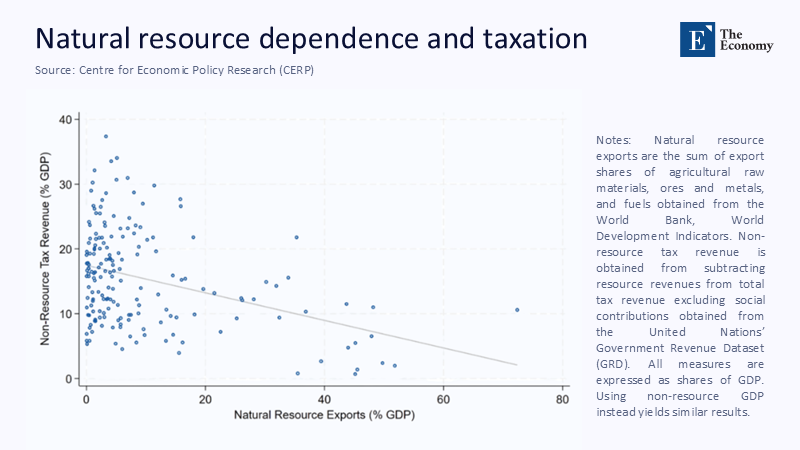

Conventional wisdom attributes weak VAT performance to natural resource rents: when oil or minerals generate easy cash, governments tend to neglect the more challenging task of taxing consumption. Yet a fresh dataset that overlays UN-Comtrade export ratios onto OECD tax statistics complicates that narrative. Resource exporters and high-tech entrepôts sit side by side on a scatterplot of low VAT-to-GDP ratios. What unites Botswana, Singapore, Chile, and Ireland is not what they sell but where their customers live. When more than 45% of GDP leaves the country as exports, the consumption base shrinks, refunds balloon, and VAT yield flattens.

Recasting the paradox around scale rather than sector exposes a deeper design problem. Policymakers who respond to low yields by simply raising rates overlook the law of diminishing returns. As rates climb in export-heavy economies, refund chicanery becomes more lucrative, widening the very gap the hike was meant to close. Alignment with the reference article’s angle thus deepens: VAT is an efficient workhorse only for countries with large domestic economies. For everyone else, unmodified adoption risks producing an ungainly creature—administratively heavy, chronically leaky, and socially regressive.

Demand-Led Giants: How Domestic Markets Anchor VAT Yields

Large internal markets generate what might be called a “demand dividend.” Following China's unification of local VAT surcharges in 2023, the levy increased to 7.9% of GDP, marking a notable rise that now encompasses the entire annual interest bill on central government debt. Japan’s 2019 consumption tax hike stabilized its pension system, and preliminary 2025 figures show the tax financing one-fifth of social security payouts. Even the United States, often cited as a VAT-free outlier, collects the equivalent of 2.4% of its GDP through state-level sales taxes, comparable to the EU average once compliance gaps are taken into account.

A cross-sectional regression of thirty-one OECD economies reveals a near-linear relationship: every one-percentage-point increase in domestic consumption share lifts VAT yield by 0.08 percentage points of GDP, holding statutory rates constant. That elasticity explains three-quarters of the variance between high- and low-performers, clarifying why modest rate tweaks net faster revenue than income-tax hikes in demand-rich nations. For educators, the dividend translates into predictable appropriations, enabling multi-year budgeting rather than annual budgeting uncertainty. Stable VAT streams finance everything from early childhood classrooms in France to lab equipment renewals in South Korea, illustrating how scale converts a blunt tax into a reliable engine for public-sector investment.

Export-Driven Economies: Structural Constraints and Fiscal Volatility

The picture flips to export champions such as Singapore, Ireland, or Costa Rica. Even after Singapore’s 2024 Goods-and-Services-Tax bump to 9%, consumption-tax revenue hovers at 1.5% of GDP—barely half the OECD norm—because zero-rated exports drain the base. Ireland refunds roughly one euro in three collected, mirroring an export-to-GDP ratio above 150%. The structural ceiling is visible in monthly cash-flow data: as exports surge, refunds spike, and net receipts stagnate.

Yet design still matters. New Zealand, whose exports equal almost half of its GDP, boasts a VAT compliance gap of under 4%—the lowest in the OECD—thanks to a single broad rate and universal e-invoicing. A replication of the European Commission’s 2024 VAT-Gap model across fourteen small open economies shows that shifting from multiple to single rates trims leakage by an average of 3.2 percentage points. Such upgrades do not erase the scale constraint but raise the ceiling, buying fiscal room for maneuver. The reference article’s insight—that VAT falters where external demand dominates—remains intact; the nuance is that intelligent architecture can mitigate, though not eliminate, the structural disadvantage.

Inequality and the Social Contract: VAT’s Regressive Shadow

Opposition to VAT often centers on the issue of fairness. In the United States, the poorest fifth of households devote nearly 8% of their income to state-level sales taxes, while the top 1% pay barely 1%. Similar regressivity plagues unitary VAT systems: Italy’s 2024 revenue review showed that households with an income below €20,000 faced an effective VAT rate 3.6 times higher than those with an income above €150,000. Without offsets, consumption taxes exacerbate inequality, particularly in export-dependent states where fiscal capacity is already limited.

Progressive relief, however, is neither theoretical nor trivial. Canada’s quarterly GST credit now refunds an average of C$557 to low-income adults, offsetting almost the entire indirect tax burden for the bottom quintile. IMF simulations released in 2024 demonstrate that converting two-thirds of reduced-rate items into direct transfers raises after-tax income for the poorest decile by 2.1% while increasing net revenue. A microsimulation built on Luxembourg Income Study data for Poland and Chile shows that pairing a single-rate VAT with a refundable child allowance trims the Gini coefficient by up to 1.4 points—the distributional punch of a three-point income-tax hike at a fraction of the administrative cost. Equity fixes, therefore, are not cosmetic; they are central to VAT’s legitimacy and the sustainability of public education.

Digital Compliance Revolution: Turning Invoices into Insight

Compliance gaps are no longer about cash registers; they are about data. Brazil’s nationwide e-invoice network now processes two billion transactions a month, flagging mismatches in real time and cutting refund fraud by 18% since 2023. The European Commission’s ViDA proposal, which is advancing toward implementation in 2026, will require intra-EU business-to-business digital reporting within forty-eight hours, thereby reducing carousel fraud windows. OECD projections suggest that if all member states adopted universal e-invoicing, global VAT losses could fall by nearly a quarter, freeing US$300 billion annually, enough to erase UNESCO’s funding gap for universal secondary education twice over.

Educational institutions can accelerate this shift. Universities rank among the largest purchasers in many countries; when they mandate e-invoices from suppliers, compliance norms ripple outward. Vocational curricula that embed real-time tax analytics supply revenue agencies with the talent they cite as their most significant bottleneck. Classrooms thus become compliance laboratories, nudging tax systems toward higher yield and greater transparency. For export-dependent states, digital enforcement is the most promising lever for squeezing additional revenue from a stubbornly narrow base without raising statutory rates.

Pros, Cons, and Political Viability: Building a Balanced Palette

Any honest assessment must weigh VAT’s celebrated neutrality and efficiency against its social costs. On the plus side, the tax is complex to evade at the final point of sale, delivers steady cash flow even during downturns, and—when refunds are prompt—imposes minimal working capital drag on exporters. Critics counter that VAT strengthens monopolistic retailers, who can better handle compliance burdens while squeezing small service providers and shifting the overall tax mix away from progressive direct levies. Empirical evidence suggests that both narratives are partly accurate and highly contingent on context. In Germany, where domestic demand is robust, VAT financed nearly half the pandemic-era stimulus without provoking public backlash. In contrast, Hungary’s 27-percent rate—the highest worldwide—spawned a grey market in cash discounts and spurred protests over regressive impacts.

Political viability, therefore, hinges on three design decisions. First, breadth: exempting too many items erodes yield and encourages lobbying, yet taxing essentials without rebates sparks outrage. Second, the speed of refunds: delays turn exporters into unwilling creditors of the state, undermining competitiveness. Third, redistribution: direct cash transfers preserve revenue while providing a cushion for people experiencing poverty. If these levers are calibrated to a national scale, VAT can serve as a pragmatic, if imperfect, revenue pillar; misaligned, it becomes a regressive revenue sieve, as the reference article cautions.

Actionable Pathways for Education Stakeholders

For universities and school systems, VAT policy is not an abstract fiscal footnote; it shapes operating budgets and student access. In the United Kingdom, where tuition is zero-rated but dormitory rents are exempt rather than zero-rated, one Russell Group university saved £38 million in 2024 by restructuring leases to reclaim input VAT—money now earmarked for bursaries and laboratory upgrades. Across the Atlantic, Washington State allocates a portion of its sales-tax growth to need-based scholarships, stabilizing enrollment among first-generation students even as federal aid lags.

Administrators can act on three fronts. First, audit supply chains to maximize input-VAT recovery and plug compliance leaks. Second, lobby for low-income credits that offset tuition hikes indirectly triggered by changes in consumption taxes. Third, partner with revenue agencies on e-invoicing pilots, turning campuses into sandboxes for digital compliance. Such collaborations have cut procurement costs by 8% at Kenya’s Egerton University and slashed refund times for research equipment at Australia’s Monash University. By engaging rather than observing, educators turn a tax debate into a tool for equity and institutional resilience.

Recalibrating the Tax Compass

The €89 billion that vanished from Europe’s ledgers last year is not an actuarial abstraction; it is the lecture hall that never got renovated, the experiment that never got funded, the scholarship that never got offered. The evidence assembled here suggests that VAT thrives when domestic demand prevails and struggles when exports prevail. Yet, design choices—such as broad bases, single rates, digital enforcement, and low-income rebates—can tilt the odds. For large economies, fine-tuning those levers protects a proven revenue workhorse. For small, export-driven states, the task is more urgent: either redesign the levy to fit structural realities or risk entrenching fiscal fragility and social injustice. Educators, administrators, and policymakers share a stake in the outcome. Align the tax with scale, equity, and data, and VAT can finance the knowledge economy without taxing opportunity. Follow any other compass, and the paradox will deepen, draining resources from the very institutions that promise shared prosperity.

The original article was authored by Rabah Arezki, a Senior Fellow at Foundation for Studies and Research on International Development (FERDI), along with three co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "The value added tax paradox in resource-dependent economies," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Arezki, R., Van der Ploeg, F., Rota-Graziosi, G., & Le-Van, D. (2025). The Value-Added Tax Paradox in Resource-Dependent Economies. CEPR.

Brookings Institution. (2025). Border-Adjustment Taxes and the Future of US Trade Policy.

Canada Revenue Agency. (2024). GST/HST Credit—How Much You Can Expect to Receive.

European Commission. (2024). Member States Made Significant Progress in VAT Compliance in 2022.

Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore. (2024). Overview of GST Rate Change.

International Monetary Fund. (2024). Designing a Progressive VAT.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2024). Consumption Tax Trends 2024.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2024). Tax Administration 2024.

Storecove. (2023). Brazil’s E-Invoice Requirements Explained.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2023). Financing the Global Education Agenda.

Wall Street Journal. (2025). Why VAT Still Tempts US Policymakers.