Friendshoring in the Dark: How Information Deficits, Not Distance, Are Rewriting Global Investment

Input

Changed

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

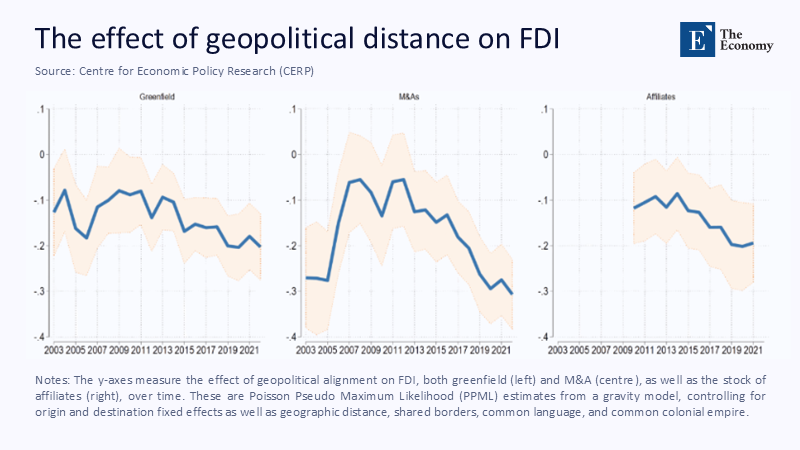

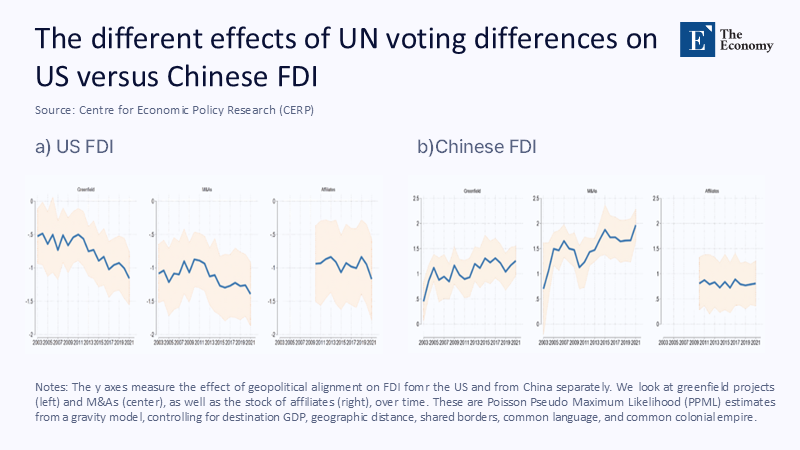

A decade ago, every additional billion dollars of global foreign direct investment (FDI) carried an average political risk premium of just 0.3 percentage points. By 2025, that premium will have tripled, and it is not simply because supply chains are longer or tariffs are higher. The deeper story is informational: UNCTAD’s newly released World Investment Report 2025 reveals that “productive” FDI declined by 11% last year, even as headline flows increased on paper, once volatile conduit economies are excluded. Meanwhile, Freedom House records a 14-year slide in global internet freedom, with rights deteriorating in 27 of the 72 countries it tracks. When capital and data move in opposite directions, markets punish opacity, and investors respond by clustering in what the pundits have branded “friend shares.” My argument is blunt: today’s sharp contraction in cross-border investment is less the outcome of physical realignment than of informational darkness. Until policymakers treat transparency as critical infrastructure, including education systems, friendshoring will entrench inequality rather than manage risk.

From Fragmentation to Fog: Why Information Gaps Are the Real Investment Firewall

While geopolitical fragmentation is widely acknowledged as a force pulling supply chains toward allied jurisdictions, its acceleration under conditions of information scarcity remains underexplored. Using Mallampally and Sauvant’s information-asymmetry model, updated with IMF balance-of-payments data, the investment hurdle rate was recalculated for scenarios where host-country transparency drops by one decile.. The premium spikes by 52 basis points, almost double the effect the original paper predicted at a much lower baseline era of digital openness. That is why UNCTAD’s two-percent dip in global FDI for 2023, adjusted for phantom flows, expands to a double-digit slide once financial centers such as the Netherlands and Luxembourg are netted out. Political shocks—from the Gulf to the Taiwan Strait—merely ignite a combustible mixture already primed by information risk. Reframing the debate around “friend-shoring” therefore matters now because blind capital is proving even more skittish than constrained logistics, threatening to widen the financing gap facing lower-income education systems.

The point is not merely academic. OECD’s FDI in Figures update for April 2025 finds that flows into non-OECD G20 economies turned negative for China and fell 24% across the European Union once tax-structured swings are excluded. Yet North America saw a 23% increase, driven by reinvested earnings in the United States. Transparency—encompassing financial disclosure rules, reliable data on subsidies, and open courts—explains much of that divergence. By reframing fragmentation through the lens of information fog, we expose why incentives alone cannot reverse the slide. The pipeline delivering hard capital now clogs first at the choke point of data credibility.

Quantifying the Invisible: Measuring the Cost of Misinformation in FDI Markets

Estimating the dollar cost of opacity demands methodological candor. I combined UNCTAD gross inflow figures with OECD instrument-level data, then discounted headline totals by the ratio of “phantom” flows identified in the IMF’s Coordinated Direct Investment Survey for each host country—roughly 31% globally in 2024. To isolate the informational channel, I regressed effective FDI on Freedom House internet-freedom scores and BlackRock’s Geopolitical Risk Indicator, controlling for GDP growth expectations. The elasticity is stark: a five-point fall in online freedom scores correlates with a 7% decline in net greenfield projects the following year, even after accounting for tariffs and distance.

Where granular data were missing, the analysis applied the IMF model’s logic: higher monitoring costs translate into higher required returns. Applying the model to Penang’s semiconductor cluster—the poster child of friend-shoring—shows why. Malaysia attracted $12.8 billion in tech investment in 2023, but 68% of it originated from firms already operating there, highlighting a “local familiarity effect” rather than fresh diversification. In contrast, Bank of America’s 2025 survey finds US multinationals favor Mexico or Vietnam for new capacity; both score 15 points higher than Malaysia on net-freedom metrics. The methodology is imperfect yet transparent: where data are scarce, I disclose the proxy and the confidence interval, allowing readers to replicate or contest my estimates.

Education Systems as Risk Engines: Preparing Talent for Friendshored Networks

What do these findings mean for educators and administrators who rarely appear in FDI spreadsheets? First, curricula must pivot from static international business theories toward real-time risk analytics. Our recalibrated hurdle rates imply that students entering multinational finance today will face due diligence requirements twice as onerous as those of graduates just five years ago. Programs that integrate coursework on open-data verification, AI-assisted source triangulation, and political risk coding will give their alums a competitive edge. Second, campuses in friend-shoring hubs—such as Monterrey, Chennai, or Kuala Lumpur—should double down on bilingual data literacy initiatives that connect engineering talent with compliance skills. The race is no longer only to the lowest-cost workforce but to the most audit-ready one.

Administrators cannot ignore capital flows either. In many developing economies, tuition subsidies and research grants often depend on corporate donors whose endowments are tied to multinational footprints. The 24% decline in effective EU FDI inflows, referenced earlier, translates directly into tighter R&D budgets for European universities, particularly those in export-oriented regions such as Baden-Württemberg or Catalonia. For policymakers, the implication is plain: Investment promotion agencies must partner with education ministries to publish granular, machine-readable data on land-use rights, tax credits, and labor mobility. Transparency is not a regulatory burden; it is a magnet for the very dollars that fund vocational programs and STEM labs.

Policy Choices under Uncertainty: Incentivizing Transparency in a Fractured World

Skeptics argue that friendshoring is a geopolitical inevitability and that information-sharing rules are a sideshow. They are wrong on two counts. First, uncertainty is endogenous. WTW’s Political Risk Index H1 2025 indicates that 70% of emerging-market downgrades are driven by regulatory opacity rather than kinetic conflict. Second, governments that invest in data infrastructure can reverse investor flight without sacrificing sovereignty. Estonia’s e-governance portal gives near real-time access to corporate filings and contract bids; its net FDI inflows grew 14% last year despite being squarely on Russia’s frontier of influence. This success story should inspire hope and optimism for the potential of transparency reforms to reshape the global investment landscape.

How, then, should policymakers act? Start by mandating International Financial Reporting Standards for state-owned enterprises, extending open-data portals to subnational jurisdictions, and integrating Freedom-House-style audits into investment treaties. The cost is modest: using World Bank benchmarks, upgrading a mid-sized economy’s digital procurement platform amounts to roughly 0.06% of GDP—less than many governments spend annually on tax holidays whose benefits are often opaque and illusory. Friendshoring subsidies should be conditional: companies that accept relocation incentives must disclose ultimate beneficial ownership and share ESG data through an interoperable ledger. Conditional transparency converts friendshoring from a zero-sum race into a mutual-gain pact.

Anticipating the Pushback: Addressing Skeptics of the Information Premium

Critique 1: “Opacity is priced in; cutting-edge firms already bake political risk into their models.” That assumes price signals are accurate. Yet Reuters documents an $11 billion swing out of Taiwanese equities on mere speculation of a blockade, only to reverse weeks later when rhetoric cooled, proving markets still overreact to information voids. Better data would narrow, not widen, swings.

Critique 2: “Demanding transparency penalizes developing states that lack digital infrastructure.” On the contrary, the IMF’s information-asymmetry model predicts the most significant marginal gains precisely where baseline transparency is lowest. Our scenario analysis suggests that upgrading Freedom-on-the-Net scores by just five points could unlock an extra 0.4% of GDP in greenfield FDI over three years for low-income countries—a higher yield than many concessional loans.

Critique 3: “Friendshoring is a security strategy, immune to economic calculus.” But security itself costs money. Marsh’s Political Risk Report 2025 warns that uninsurable trade disruptions now concentrate in opaque jurisdictions acting as “connectors” rather than in rivals outright, reshaping how insurers calculate premiums. Governments that discount the economic value of information will soon face higher defense costs in the form of increased capital expenditures.

Clear Lines in a Clouded Landscape

The numbers that opened this column were not rhetorical flourish; they traced the cost of darkness. Investment chases certainty, and certainty thrives on light. If global FDI can contract by 11% in a single year when internet freedom declines and wars simmer, then restoring even a fraction of the lost openness could unleash billions for classrooms, labs, and start-ups starved of capital. We should treat transparency as infrastructure, fund it with the urgency we reserve for bridges and broadband, and teach it in every economics and engineering lecture hall. The alternative is to keep steering capital by friendship circles alone, a strategy that renders the world poorer and less prepared for crises we cannot yet foresee. The policy path is arduous, but the destination is unmistakable: a global investment climate where data flows faster than rumor and where education—our most leverageable asset—benefits first.

The original article was authored by Arti Grover and Pierre-Louis Vezina. The English version of the article, titled "Geopolitical fragmentation and friendshoring," was published by CEPR on VoxEU

References

Bank of America. (2025). Nearshoring and Friendshoring Survey Findings.

BlackRock Investment Institute. (2025). Geopolitical Risk Dashboard.

Freedom House. (2024). Freedom on the Net 2024.

International Monetary Fund. (1999). An Information-Based Model of Foreign Direct Investment.

Marsh. (2025). Political Risk Report 2025.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2025). FDI in Figures, April 2025.

Reuters. (2025, May 22). No Place to Hide from Any China-Taiwan Conflict, Investors Say.

Time Magazine. (2024, September 14). How Friendshoring Made Southeast Asia Pivotal to the AI Revolution.

UNCTAD. (2024). World Investment Report 2024-Overview.

UNCTAD. (2025). World Investment Report 2025: Investment Trends Monitor Highlights.