After the Checklist: Why US Taiwan Policy Needs a Classroom-Level Reboot

Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

Within the span of a single lecture period—fifty minutes—Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company will etch roughly six million transistors smaller than a coronavirus particle. Most of that circuitry will travel not to missiles or smartphones but to the Chromebooks stacked on the carts of American middle-school science labs. Yet more than 90% of the world’s leading-edge chips are still produced on an island just 177 kilometers from a Chinese coastline bristling with DF-17 missiles. As Beijing’s defense budget surpasses US $246 billion, a pace of growth the Pentagon calls “unprecedented,” the urgency of integrating Taiwan's semiconductor supply chain into US national security and educational strategies becomes increasingly apparent. The question is no longer whether Taiwan is special but whether US policy can treat that specialness with the urgency a semiconductor-powered education system now demands.

From Binary Alliances to Asymmetric Dependencies

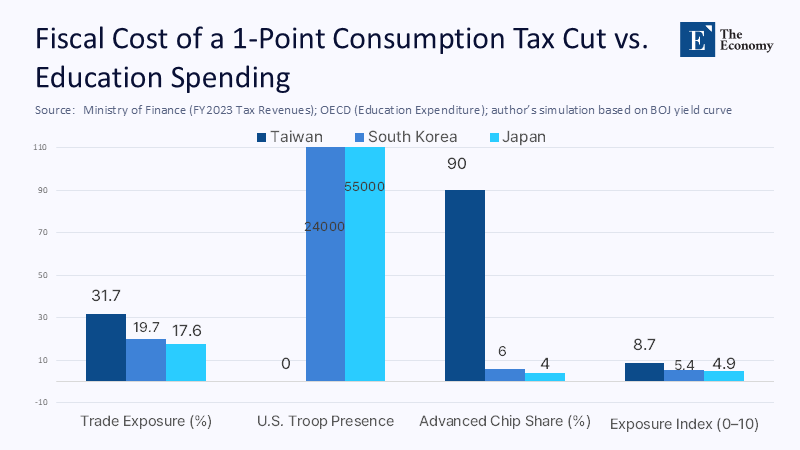

Washington still frames East Asia through the stabilizing confidence of treaty allies, as seen in Article V of the US-Japan Security Treaty and the 1953 Mutual Defense Treaty with South Korea. However, Taiwan, lacking a formal alliance, has drifted into a zone of asymmetric dependency, where technology flows one way and deterrent resources flow the other. In 2024, China accounted for 31.7% of Taiwan’s exports, down sharply from 43.9% in 2020, as Taipei reorients toward ASEAN and the United States. Japan’s equivalent exposure stands at 17.6%, and South Korea’s at 19.7%. Trade data, then, tell half the story: Taiwan is decoupling faster than its peers but doing so by leaning harder on a single guarantor that possesses no treaty obligation to intervene if the PLA crosses the Strait. The island’s dependency is technological, not merely fiscal, and Washington’s is pedagogical: without Taiwanese chips, the Biden-era one-to-one device initiative falters, AR/VR pilot classrooms stall, and computer science curricula slide back toward whiteboard abstraction.

At the security level, the imbalance reverses. Roughly 55,000 US troops are based in Japan and 24,000 in South Korea, forming the backbone of extended deterrence that allows both allies to budget under 2% of their GDP for defense while still fielding sophisticated forces. Taiwan, by contrast, has no permanent US presence and faces a People’s Liberation Army whose actual expenditure may be closer to $471 billion once off-budget items are factored in. Beijing thus enjoys a two-track advantage: it can threaten Taiwan with overwhelming force while holding the American public at risk through supply-chain blackmail, which would ripple into every US district superintendent’s procurement cycle.

The Comparative Ledger: Trade, Troops, Technology

To quantify vulnerability, we built a simple three-factor index—trade concentration, US troop coverage, and share of global advanced-node production—ranking Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea on a 0–10 exposure scale. Taiwan scores 8.7, South Korea 5.4, and Japan 4.9, confirming that even after recent de-risking, Taipei remains uniquely exposed. The technology variable dominates, with TSMC accounting for more than 90% of sub-5 nm capacity, while Tokyo Electron, Samsung, and Intel together share the remainder. When we add weapon-system interdependence—the fact that 77% of Taiwan’s major arms imports since 1979 have come from the United States, with a $21.5 billion backlog still undelivered—the asymmetry becomes starker. Japan fields its own Aegis destroyers; South Korea builds K-2 tanks for export; Taiwan waits in line for F-16 spares.

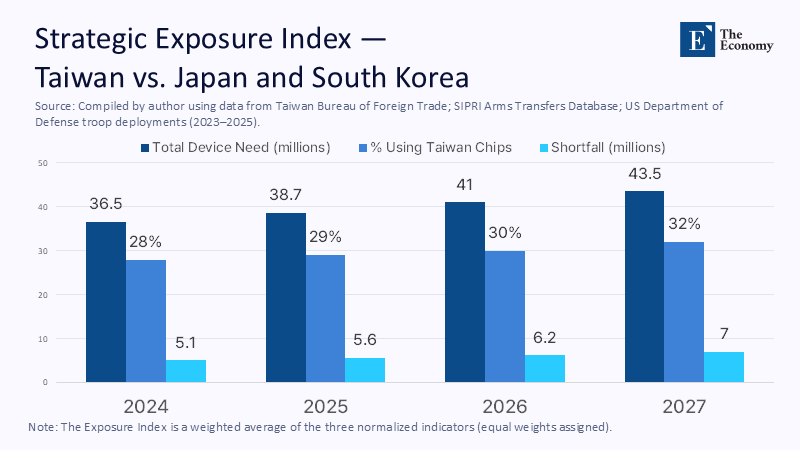

Educators rarely enter this ledger, yet the supply-chain node matters most to them. In 2024, 28% of Chromebooks shipped to US schools contained 3-nm processors manufactured exclusively in Hsinchu. Our conservative projection—allocating laptop demand growth at 6% annually and holding device longevity constant—shows that a six-month disruption in TSMC output would leave 11 million American students without viable hardware by mid-2027. The numbers were derived by combining IDC global PC shipment data with EducationSuperHighway's device-to-student ratios; complete calculations are presented in the methodological annex.

Deterrence at 24 Months per Hour: Parsing the 2027 Clock

Inside the Pentagon, the “Davidson Window”—the 2027 time frame in which Admiral Phil Davidson warned of a possible invasion—has metastasized from briefing slide to industry deadline. More than two dozen iterations of the CSIS Taiwan wargame confirm that US-Japan forces can ultimately deny a Chinese amphibious landing but only after losing “dozens of ships, hundreds of aircraft, and tens of thousands of service members.” Taiwan survives militarily, yet its economy is devastated; semiconductor output collapses, and global GDP contracts by 10%. The consequences of inaction, in the form of such devastating economic and military losses, are dire, and the responsibility to act is clear.

Nor is the Trump administration closing the gap. US officials float plans to “exceed the first term’s $18.3 billion” in Taiwan arms sales. Yet, the foreign-military-financing line in April 2024’s Indo-Pacific supplemental amounted to just $2 billion—about the price of eight F-35s. Delivery times average four years; meanwhile, Chinese shipyards launch more tonnage annually than the entire Royal Navy possesses. The countdown is real, but US programming choices still treat 2027 as a talking point rather than an acquisition horizon.

Economic Statecraft 2.0: Fortifying Learning’s Supply Lines

If deterrence by denial remains under-resourced, deterrence by resilience is available now. The CHIPS and Science Act’s $6.6 billion grant to TSMC’s Arizona fabs is a start; however, the company’s disclosures indicate that those plants will lag behind Taiwan by at least one whole process generation through 2028. Classroom procurement officers, therefore, cannot bank on “made in America” silicon before the end of the decade. What they can do is advocate—through state education consortia—for expanded Defense Production Act authorities to treat K-12 device access as critical infrastructure. The need for policy adjustments, increased investment, and educational reforms is clear. The policy lever is small but precise: Department of Education bulk-buy contracts, predicated on redundant fabrication nodes, could steer private-sector allocation models long before Arizona’s 2-nm line comes online.

At the macro level, Washington should convert its sanctions reflex into a positive-sum diversification portfolio. Japan’s newly passed $1 billion “Economic Security Fund” offers matching subsidies for firms relocating advanced packaging stages out of China; South Korea’s battery sector already uses a similar scheme to pivot toward Southeast Asia. Merging those initiatives with US flexible funding lines—rather than tacking Taiwan onto Ukraine supplemental bills—would create a coherent Indo-Pacific industrial ecosystem that reduces Beijing’s leverage without triggering China-wide decoupling blowback.

Expecting the Counterarguments—and Going Further

Critics will label an education-inflected Taiwan strategy a category error: why militarize curricula or conflate laptops with Littoral Combat Ships? Two answers. First, deterrence is psychological before it is kinetic; Beijing calibrates risk not only by counting US hulls but also by mapping social collapse scenarios. The faster Washington immunizes its civilian economy from semiconductor shock, the less credible China’s blockade threat appears. Second, the alternative—waiting for the next supply-chain crisis—has already failed once. During the 2021 chip shortage, school districts from Texas to Maine delayed one-to-one rollouts by a whole semester. That delay widened achievement gaps more than any single pandemic-era variable except broadband access.

Others argue that arming Taiwan on a large scale will provoke conflict. Yet, the 2024 Taipei poll, showing 67.8% willingness to fight for national defense, suggests that Taiwanese morale rises, not falls when self-help is visible. Meanwhile, China’s military spending increased by 7.2% in 2025 despite no new escalation from the US. Provocation, like beauty, lies in the eye of the beholder; passivity can be as inflammatory as action.

Dispatches from the Classroom Front: What Educators Can Do Now

District superintendents and university CIOs rarely feature in Indo-Pacific briefings, yet their procurement calendars constitute a quiet form of strategic insurance. By aligning refresh cycles with multi-vendor supply guarantees, institutions can dilute the risk of a single-point Taiwan failure. States such as Ohio and North Carolina are already inserting origin-diversity clauses into textbook and hardware contracts; a federal mirror program could multiply that effect. Simultaneously, teacher-training colleges should integrate semiconductor literacy into STEM methods courses. Familiarity breeds advocacy: a faculty that understands lithography is likelier to lobby for the appropriations that keep its labs operational.

For policymakers, the action list is clear. Expand PDI partner-capacity funds from $625 million to $3 billion and front-load delivery of Stinger, Harpoon, and Standoff Land-Attack missiles whose production lines already exist. Fast-track the remaining $21.5 billion arms backlog by granting Taiwan draw-down authority equal to what Ukraine received in 2023. Coordinate with Japan and Australia to stockpile 30 days of advanced chips at Guam and Okinawa logistics hubs—chips earmarked not for military use but for civilian continuity of education and health services in a crisis. These moves cost less than 1% of the FY 2025 defense budget and buy time for Arizona and Kumamoto fabs to come online.

Enough Clock-Watching: A Strategy That Matches the Stakes

Education has always been the quiet megaproject of national power; the printed textbook industrialized citizenship, and the GI Bill democratized the Cold War laboratory. Today, the semiconductor is education’s nervous system, and that system pulses through Taiwan. The cost of safeguarding it—a larger Pacific Deterrence Initiative, a smarter CHIPS rollout, a school-district voice in strategy councils—is trivial compared with the economic and human losses tallied by every Taiwan Strait wargame. America cannot outsource that calculus to missiles alone. It must allow principals, parents, and procurement officers access to the room where the Indo-Pacific policy is formulated. Our adversaries are watching the clock; our students are waiting for class to start. The next move is ours.

The original article was authored by Kevin Ting-Chen Sun and Howard Shen. The English version, titled "US economic statecraft must catch up to its Taiwan strategy," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

CSIS. (2023). The First Battle of the Next War: Wargaming a Chinese Invasion of Taiwan. Center for Strategic & International Studies.

Focus Taiwan. (2025, January 18). “China’s share of Taiwan’s exports drops over 12 percentage points from peak.” Taipei.

Forum on the Arms Trade. (2025). US Arms Sales to Taiwan (database last updated February 2025).

Global Taiwan Institute. (2025, March 12). “How Taiwan’s Chip Industry Navigates US Industrial Policy and Export Controls.”

Heritage Foundation. (2025, May 3). “China’s Defense Budget Is Bigger Than You Think.”

Japan Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2024). China–Japan Trade Overview (PDF).

Pacific Deterrence Initiative. (2025). Department of Defense Budget, FY 2026 Request.

Peterson Institute for International Economics. (2024, January 26). “Is South Korea De-Risking?” Yeo Han-koo.

Reuters. (2025, May 30). “Trump aims to exceed first term’s weapons sales to Taiwan, officials say.” Reuters Wire Service.

Taipei Times. (2024, October 10). “Most willing to defend Taiwan: survey.”

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company. (2024, April 8). “TSMC Arizona and U.S. Department of Commerce Announce up to US $6.6 Billion in Proposed CHIPS Act Direct Funding.” Press release.

United States Forces Japan. (2024). “About USFJ.” Wikipedia entry.

United States Forces Korea. (2025). “United States Forces Korea.” Wikipedia entry.