Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

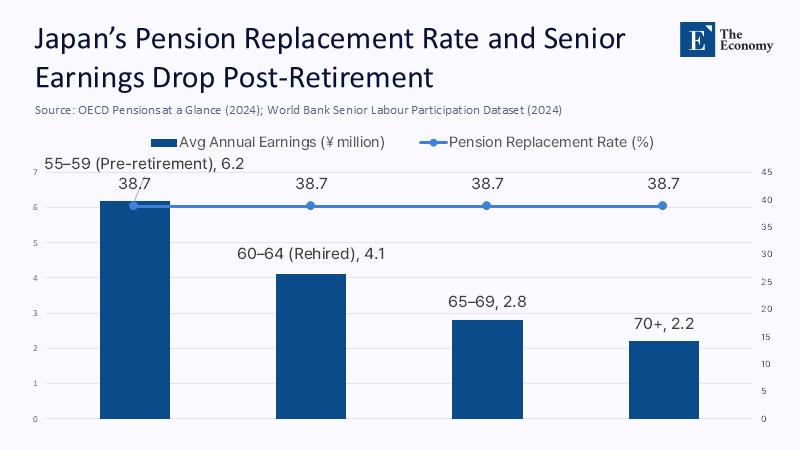

Japan is currently facing a pressing issue of 'productive aging', which is more of a fiscal pressure valve. This situation is compelling almost one-third of the country’s over-65s to return to low-wage retail jobs and nursing care wards. The public pensions, which replace barely two-fifths of their former earnings, and the depletion of household savings for millions, have escalated the urgency of this issue.

The statistical mirage of late-life work

For politicians in Tokyo, the fact that 9.1 million Japanese aged 65 and above still hold jobs is presented as proof that longevity has been monetized. Yet disaggregated labor-force tables paint a darker canvas. Wholesale and retail trade absorb 1.75 million seniors, health and welfare another 1.07 million, and assorted service roles the bulk of the rest, all sectors where hourly pay sits 30–40% below the national median and offers virtually no pensionable top-ups. In other words, Japan’s senior employment boom is less a triumph of human capital utilization than a statistical echo of inadequate income security. Evidence from the 2024 Labour Force Survey shows the employment rate for men collapses from 84% at age 60–64 to 26% beyond 70, while women’s participation halves over the same span, confirming that the majority who keep working do so under severely diminished terms. The “silver shift” discourse, therefore, mistakes compulsion for choice: an aging society is celebrating a symptom of its failure to maintain income.

Poverty wearing a uniform

Relative income poverty now ensnares roughly one in five Japanese seniors—already well above the OECD mean—but the headline masks brutal subgroup disparities. A 2023 analysis of welfare ministry microdata by Aya Abe found that 44.1% of single women over 65 lived below the poverty line, compared with 30% of single men and just under 15% of the total population. That gender skew is amplified by asset fragility: two decades of deflationary wage drift and care obligations mean the median financial cushion for single older women is under four million yen—barely 18 months of average living costs in metropolitan prefectures. Unsurprisingly, the visible consequence is retail uniforms and convenience-store aprons on bodies that ideally would be enjoying genuine retirement. Less visible is the psychological toll: a Cabinet Office well-being panel recorded a 28% increase since 2020 in reported “financial insecurity” among female seniors, a marker linked to higher hospital admissions for stress-related illness. The poverty narrative is, therefore, both material and mental, and its feminization destabilizes Japan’s vaunted social compact.

The intergenerational trapdoor

Every serious attempt to improve pension adequacy hits an actuarial wall. The old-age dependency ratio, already the planet’s worst, surpassed 50% in 2021 and is on track to reach 79% by 2050, meaning fewer than 1.3 workers will be available per retiree. Expanding contribution rates would pass a larger fiscal burden to shrinking cohorts that already bear the second-highest social security load in the OECD and confront government debt at 261% of GDP. Raising the eligibility age narrows the pension funding gap on paper. Still, it extends a decade-long stretch between mandatory corporate retirement at 60 and full pension access, during which workers are rehired on short-term contracts at wage discounts exceeding 30%. Thus, the system quietly off-loads its actuarial imbalance onto households through low-quality, necessity-driven jobs, entrenching the very poverty it was designed to prevent while risking social legitimacy among younger taxpayers who see little return on ever-larger payroll deductions.

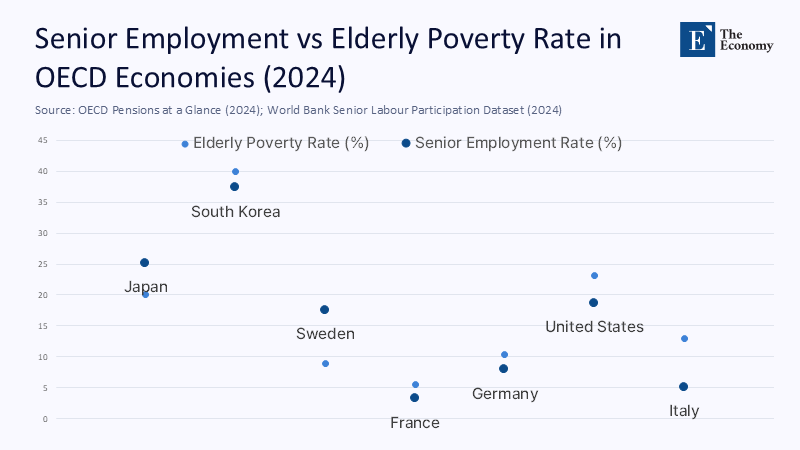

A Cautionary Korean mirror

South Korea illustrates the peril of mistaking employment quantity for welfare quality. Seoul boasts the world’s highest senior employment rate—above 37%—yet elderly poverty rates hover near 40%, nearly triple the OECD average. Korea’s 2014 expansion of the Basic Old-Age Pension lifted income transfers without re-engineering labor-market segmentation; the outcome was a larger cohort of working poor seniors juggling parcel-sorting shifts and street-cleaning gigs. Japan’s poverty numbers are lower, but they are moving in the same direction, confirming that bolting a bigger pension onto an unreformed low-wage labor silo merely recycles fiscal outlays into subsistence earnings rather than sustainable well-being. The Korean case warns that if Tokyo limits itself to parametric tweaks of benefit formulas while leaving wage structures and job design untouched, poverty will scale faster than transfers can offset.

The wage curve that punishes longevity

Japan’s seniority-based wage model remains the structural culprit. Corporate pay peaks in the mid-fifties and then drops sharply when employees are rehired as “contract workers” after the statutory retirement age of 60. The OECD’s 2024 Survey calculates that 70% of firms impose such mandatory exit gates, and post-retirement hourly earnings fall by an average 3of 0% for identical tasks. Reformers focus on abolishing the retirement rule, but the greater prize is decoupling pay from tenure altogether. A “two-band” wage schedule, piloted by a consortium of mid-sized manufacturers, starts band B at 90% of an employee’s last band-A wage, escalates annually with performance metrics identical to those applied to younger staff, and extends promotion opportunities indefinitely. Internal cost modeling reveals a mere 4-per-cent increase in lifetime payroll obligations but an 18-per-cent rise in average earnings after 60, which is enough to close half of the net replacement rate gap without new public transfers. Daikin’s 2024 sustainability report notes that eliminating the automatic retirement cliff for frontline technicians reduced churn and saved ¥3 billion in hiring costs—an implicit productivity dividend that dwarfs traditional seniority savings.

The health-at-70 fallacy

Some commentators argue the solution is biomedical: make septuagenarians as healthy as 40-year-olds and raise retirement ages. The premise crumbles under epidemiological data. Wholesome life expectancy gains since 2010 have averaged under six months per calendar year, far short of the pace needed to offset the explosion in the dependency ratio. Moreover, morbidity compression remains uneven: chronic musculoskeletal conditions rise steeply after 68, regardless of medical advancements, limiting the range of physically demanding roles seniors can fill. Ergonomic redesign, flexible hours, and telework portals can expand workability, but they cannot—short of science-fiction breakthroughs—render burger-flipping or parcel-lugging an attractive late-life career. By anchoring solutions exclusively in biomedical optimism, policymakers risk overlooking the immediate economic levers that determine whether older workers earn a dignified wage or struggle to make ends meet.

Pivoting to a silver-productivity ecosystem

Where Japan does hold an advantage is in digital infrastructure. Under the Society 5.0 roadmap, pilot logistics hubs utilizing collaborative robots (“cobots”) report throughput gains of over 30% while reducing manual lifting tasks by half, creating supervisory and programming niches that pay 1.4 times the retail wage and are accessible to trained seniors. Scaling such models could absorb 250,000 older workers into higher-value positions by 2030. A prefecture-funded “Silver Skills Cloud,” now in beta, matches retired engineers and language teachers with micro-contracts in tutoring, translation, and design. Early evaluations show median hourly earnings 55% above convenience-store rates and a 20-point increase in self-reported life satisfaction among participants. The government can accelerate diffusion by converting the existing Employment Stabilisation Subsidy into a payroll-tax rebate that co-funds reskilling. For every yen a firm spends on upgrading skills for employees over 55, it receives a half-yen credit, up to ¥200,000 per worker. The outlay—roughly 0.3% of GDP if half of all senior employees take a 40-hour digital-skills module—costs barely one-third of what Japan already spends on early-retirement compensation in construction and complements rather than burdens the pension budget.

Targeted transfers without bankrupting the young

Fiscal room exists to strengthen the floor without pushing the liability onto younger taxpayers. Phasing out the spousal-dedication tax break, which disproportionately benefits dual-earner households in the top two deciles, would net 0.4% of GDP, sufficient to raise the basic pension for the lowest-income quintile of seniors by 15%. Asset-tested supplements, modeled on New Zealand’s surcharges, would protect single older adults—now the poorest demographic slice—while avoiding across-the-board benefit hikes. Coupled with the wage-curve reforms, higher senior incomes flow from productive work rather than payroll levies on a shrinking youth cohort, aligning incentives instead of pitting generations against one another.

Re-imagining the social contract

At its core, Japan’s impasse is less an actuarial headache than a crisis of economic citizenship. By allowing senior employment to proliferate in the lowest tiers of the wage ladder, the polity has transformed an achievement—life span that once symbolized national progress into a vector of humiliation. Younger workers, confronted with stagnant real wages and ballooning social security contributions, understandably doubt the fairness of a system that demands they underwrite a pension promise sabotaged by low-quality jobs. Restoring legitimacy means repositioning seniors not as emergency stop-gaps but as full participants in value creation, with remuneration that signals respect rather than pity. The reforms sketched above—performance-based pay continuity, precision-targeted pensions, and digitally enabled role redesign—together forge a path that honors longevity while mitigating fiscal risk.

Recovering the absolute longevity dividend

Japan does not need its septuagenarians to mimic the physiologies of thirty-somethings; it requires an economy that values seasoned expertise over birthday milestones. Performance-priced wages mean aging no longer triggers a one-third pay cut—a pension floor targeted to the genuinely needy lifts vulnerable women without crushing younger taxpayers. A silver economy strategy built on cobots, telecare, and micro-contract platforms turns older workers from statistical liabilities into productivity multipliers. The choice is stark: continue celebrating an employment-rate mirage that hides poverty or reclaims longevity as an economic asset that enriches all generations. The latter demands the courage to rewrite wage norms and reallocate subsidies toward skills rather than severance. However, the reward is profound—a Japan where work after 65 is a respected option, not a survival imperative, and where living longer no longer means living in poverty.

The original article was authored by Yasuo Takao, a political scientist specializing in comparative politics and international relations, with a geographical focus on Northeast Asia and the United States. The English version, titled "Japan’s senior employment challenge," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Abe, A. (2023). Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions: Gender gaps in late-life poverty. Asahi Shimbun Digital.

Asianews Network. (2025). South Korea’s senior poverty increases for second straight year.

Business Korea. (2025). South Korea faces rising elderly poverty amid rapid ageing.

Daikin Industries. (2024). Sustainability Report 2024.

East Asia Forum. Takao, Y. (2025). Japan’s senior employment challenge.

International Federation of Robotics. (2024). Collaborative automation is driving productivity.

Kyodo News. (2024). Japan’s over-65s hit record high 36.25 million, one in four working.

OECD. (2024). Addressing demographic headwinds in Japan: A long-term perspective.

OECD. (2024). Economic Surveys: Japan 2024.

OECD. (2023). Working Better with Age: Japan.

World Economic Forum. Tochibayashi, N., & Ota, M. (2024). How companies are addressing workforce shortages through senior employment in Japan.