Input

Changed

Every statistic about public trust in science reveals less a knowledge gap than an abyss of distrust, a chasm that reason alone cannot bridge. Despite decades of data, surveys, and outreach campaigns, roughly three-quarters of Americans—76% in the latest Pew Research Center poll—report having at least some confidence in scientists to act in the public’s best interest; yet, more than one in four express little to no trust at all. This paradox highlights a fundamental insight: no matter how incontrovertible the facts, the battleground of belief is defended not by ignorance but by deep-seated distrust. A significant challenge in science communication appears to stem from the deeply embedded role of identity and mistrust, which can insulate unsupported beliefs from correction. Only by reimagining policy through the lens of relational trust and epistemic humility can we hope to shift hearts—and minds—beyond the echo chambers of certainty. This shift in science communication strategies is crucial to building trust and bridging the gap between scientific facts and public trust.

The Trust Deficit: Beyond Knowledge Gaps

For too long, educators and communicators have operated under the illusion that disseminating more data—charts, studies, infographics—would naturally erode pseudoscientific convictions and conspiracy‐driven narratives. Yet, real-world outcomes contradict this logic: in controlled trials across health, climate, and technology domains, participants exposed to corrective information often reinforce their original stance, a phenomenon known as the “backfire effect.” What underlies this counterintuitive reaction is not an intellectual deficiency but an affective firewall: a refusal to accept that one’s beliefs might be vulnerable. Laboratory and field experiments confirm that even highly educated individuals when confronted with evidence that threatens their worldview, will dismiss or reinterpret the data to preserve existing convictions. The conclusion is inescapable: filling informational deficits will not suffice because the real gap is one of trust—a refusal to believe the messenger to grant legitimacy to the institution of science itself. Failing to recognize this distinction is to continue speaking into a void; it is time to shift from monologues based on facts to dialogues grounded in trust.

Identity and the Fortress of Belief

Understanding why facts fail requires examining the social architecture of belief. Cognitive scientists have long documented that individuals do not process evidence in a vacuum; instead, they filter information through cultural and ideological priors that affirm in‐group identity. When scientific findings clash with group norms—whether political, religious, or social—many will receive them as threats, deploying sophisticated mental gymnastics to dismiss or neutralize the message. Paradoxically, greater scientific literacy can exacerbate this phenomenon: expertise provides more ammunition to rationalize preexisting biases, leading to greater polarization among the most knowledgeable cohorts. It is not a question of brainpower but of brain loyalty—where loyalty to identity trumps deference to evidence. Recognizing belief as a social glue rather than a rational conclusion demands that any policy aimed at shifting public opinion must first reckon with the bonds of identity that render audiences impervious to pure data.

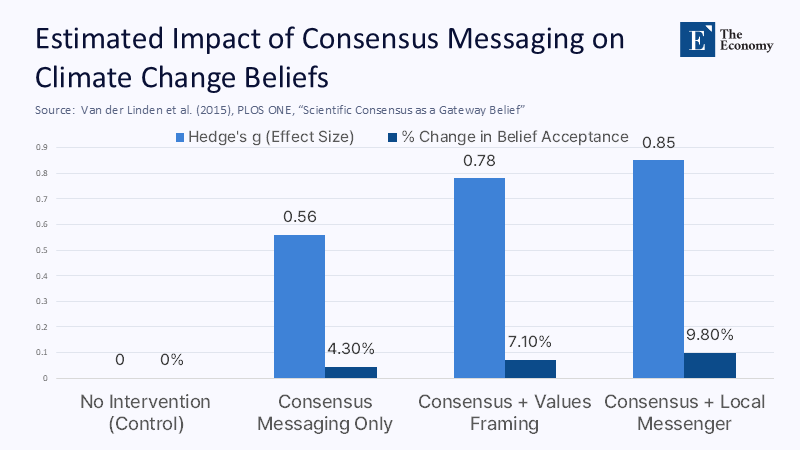

Consensus Messaging: Hype or Hope?

One of the most prominent interventions in recent years—consensus messaging—seeks to correct widespread misperceptions about the level of agreement among experts on topics like climate change or vaccine safety. A prominent study suggests that informing people of the near-unanimous consensus among scientists can open a “gateway” to greater acceptance of evidence-based policy. Indeed, meta-analytic reviews indicate that such messaging yields modest gains, shifting beliefs by a few percentage points and incrementally nudging policy support. But when hundreds of millions remain unconvinced, a 3–5% uptick in acceptance is but a drop in the ocean.

Moreover, those most hostile to the consensus often double down, viewing the messaging as an elitist ploy. The takeaway is sober: consensus messaging can be part of a broader toolbox, but it cannot be the cornerstone of a communications strategy that aims to transform deeply held convictions. For coalition builders and policy designers, this means investing in trust-building infrastructures, not merely amplifying the voices of experts.

Quantifying the Divide: A Data‐Driven Diagnosis

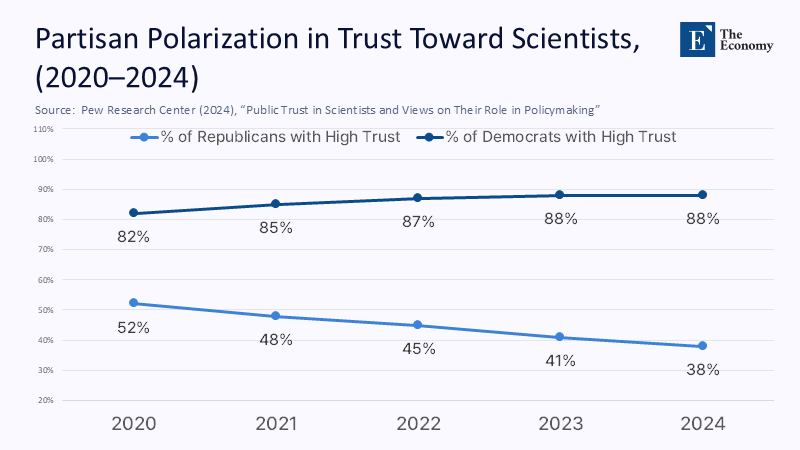

To grasp the scope of the trust chasm, consider that political affiliation now predicts scientific trust as strongly as education did in the past. Recent polling shows that while 88% of Democrats profess confidence in scientists, only 66% of Republicans do—a gap that has widened over the past half-decade as partisan media landscapes have fractured around scientific controversies. Even within demographic subgroups presumed to be receptive—such as university‐educated seniors or high‐income parents—pockets of skepticism persist, driven not by ignorance but by a conviction that expert institutions no longer represent their values.

When designing a campaign to boost vaccine uptake or decarbonization initiatives, policymakers must confront the reality that tens of millions will view the message through lenses of suspicion. Quantitative targets predicated on near-universal buy-in, therefore, rest on a fantasy; effective policy frameworks must be modular, accommodating subpopulations that may disengage from standard scientific appeals.

Beyond Facts: Relational Trust and Community Engagement

If distrust is the primary barrier, then the remedy lies not in gathering more data but in fostering human connection. Community engagement models—from participatory action research to local science cafés—aim to integrate scientific dialogue into the social fabric of neighborhoods, faith groups, and civic organizations. In these contexts, the messenger often matters more than the message: a trusted pastor or hometown physician can open ears that national experts cannot. Longitudinal studies of community-based vaccination drives demonstrate that partnerships formed over months or years, characterized by active listening and co-created solutions, yield uptake rates significantly higher than those achieved by mass-media campaigns. The effectiveness of community engagement in fostering trust and increasing uptake rates underscores its importance in science communication.

Embracing Epistemic Humility in Policy Design

To reimagine science policy for a skeptical era, we must embed epistemic humility at every level of decision‐making. This entails acknowledging uncertainty as an asset rather than a liability. When agencies emphasize the provisional nature of findings, they paradoxically enhance credibility by avoiding the hollow certainty that breeds resentment. Regulatory bodies can establish “stakeholder science advisory councils,” inviting non-expert representatives to review draft guidance and voice their concerns before it is finalized. Educational systems can introduce curricula on the sociology of knowledge, teaching students to interrogate both evidence and the processes by which it is produced. Funding mechanisms can prioritize “knowledge co‐production” grants that require scientists and community groups to define research questions jointly. These structural reforms shift the narrative: science becomes not an imposition of superior intellect but a collective enterprise in which lay perspectives shape rather than merely consume expert insights.

The Myth of a Magic Bullet

Driven by frustration, many of us long for a “silver bullet”—a campaign or slogan that will snap recalcitrant audiences into epistemic compliance. Yet decades of effort across public health, climate advocacy, and technology adoption remind us that no single intervention shifts minds en masse. Attempts to brand anti‐science adherents as the “silent minority” or to shame them into submission often backfire, reinforcing in‐group identity by casting dissenters as embattled heroes. Even interventions designed to highlight the plurality of science supporters—such as live polls showing “real‐time” agreement—can be dismissed as manipulated or unrepresentative. Acceptance of facts, it seems, cannot be coerced by clever framing alone; it emerges through a tapestry of sustained relationships, context‐sensitive messaging, and institutional reforms that transform how people experience science in their daily lives.

Toward a New Praxis: Iteration and Adaptation

If trust cannot be manufactured, it can be cultivated through iterative pilots, rigorous evaluation, and willingness to pivot. Funders and policymakers should treat public understanding not as a static target but as a dynamic ecosystem, subject to shocks, feedback, and evolving narratives. By adopting principles from adaptive policy design—such as rapid prototyping of engagement models, real-time data collection on trust metrics, and modular resource allocation—stakeholders can learn what works, for whom, and under what conditions. For example, pairing micro-grants with local science educators and embedded ethnographers can reveal the narratives that resonate in specific communities, enabling the scale-up of successful pilots while halting investments in faltering approaches. Such an adaptive infrastructure requires tolerance for failure, clear metrics for trust (e.g., Net Promoter Scores for scientific institutions), and governance structures that center on the diversity of thought as a strength rather than a hindrance.

Accepting Human Limits—And the Path Forward

Ultimately, we must confront an uncomfortable truth: many individuals may never yield their convictions, no matter how compelling the evidence or sincere the outreach. To attribute this to a personal failing of communicators is to misunderstand the depth of identity-driven resistance. Instead, we should view these hard cores not as targets for conversion but as signals to refine our focus on the persuadable middle—a segment that, though smaller than we would like, remains the key to incremental progress. By channeling our energy into building relational trust with this group while deploying adaptive, community-rooted interventions, we lay a foundation for collective decision-making that tolerates dissent without capitulating to falsehoods. Accepting that no universal “magic” exists is not defeatism; it is maturity—a recognition that enlightenment is a continuous, negotiated process rather than a once‐and‐for‐all victory.

By reframing science communication and policy from an information-delivery model to a trust-nurturing enterprise, we honor both the complexity of human belief and the rigor of scientific inquiry. Only by weaving empathy, humility, and adaptability into our strategies can we hope to navigate the abyss of distrust and build a resilient public discourse—one in which facts matter not because experts wield them, but because they are co-owned by a society willing to learn together.

The Economy Research Editorial

The Economy Research Editorial is located in the Gordon School of Business and Artificial Intelligence, Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence

References

FiercePharma. 2023. “Pew Sees Doubling of Americans Who Distrust Scientists since 2019.” FiercePharma, November.

Hurst, Laurence D. 2023. “Why Some People Don’t Trust Science – and How to Change Their Minds.” PhillyVoice.

Kahan, Dan M., and Donald Braman. 2007. “Culture and Identity-Protective Cognition: Explaining the White-Male Effect in Risk Perception.” Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 4(3): 465–505.

Larson, Heidi. 2021. “Heidi Larson, Vaccine Anthropologist.” The New Yorker.

Nature. 2024. “US Trust in Scientists Plunged During the Pandemic — but It’s Rebounding.” Nature.

Pew Research Center. 2024. “Public Trust in Scientists and Views on Their Role in Policymaking,” by Alec Tyson and Brian Kennedy. November 14.

The Guardian. 2025. “The People Fighting to Get Through to Anti-Science Americans: ‘It’s Just Talking to Each Other’.” January 13.

Van der Linden, Sander L., Anthony A. Leiserowitz, Geoffrey D. Feinberg, and Edward W. Maibach. 2015. “The Scientific Consensus on Climate Change as a Gateway Belief: Experimental Evidence.” PLOS ONE 10(2): e0118489.