Tariff Shock, Tuition Shock: How Trade Brinkmanship Threatens America’s Learning Economy

Input

Changed

This article was independently developed by The Economy editorial team and draws on original analysis published by East Asia Forum. The content has been substantially rewritten, expanded, and reframed for broader context and relevance. All views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the official position of East Asia Forum or its contributors.

Imagine the impact of a single border tax so significant that it would withdraw the rough equivalent of every state’s entire community college appropriation—USD 110 billion—out of the economy in a single fiscal year (Yale Budget Lab, 2025). This is the projected toll of President Donald Trump’s latest tariff schedule, a slate of import duties reaching up to 40% and set to take effect on August 1 unless new deals materialize. Translate those lost dollars into classrooms, and you have funds sufficient to pay the annual salary of more than 1.6 million public school teachers or to provide free lunches for every US student for a decade. The numbers land like a gavel: trade policy is no longer a sideshow for economics desks—it is an existential education story demanding urgent, sector-specific scrutiny.

Reframing the Trade Debate: From Cargo Ships to Campus Corridors

Trade commentary usually stops at ports and factory gates, yet the knockout blow of tariff policy lands deepest in America’s classrooms. By treating customs duties as a narrow diplomatic lever, the national conversation overlooks how price shocks ripple through state equalization formulas, local bond markets, and household budgets, ultimately financing education. Tariffs function, in effect, as an unfunded federal mandate on education, redistributing resources away from instruction and toward bureaucratically unplanned price increases. Recasting the story in these terms reveals an accountability gap: those who set trade rules rarely bear the educational consequences of their decisions.

Taking this angle alters the stakes of the August deadline. If negotiations collapse, the average import tax is expected to rise to 17.6%, the highest level since 1934 (Barron’s, 2025). Conventional analyses focus on consumer prices and broad inflation. Still, they overlook the narrower budget elasticity of districts because nearly 80% of K-12 operating outlays are tied to personnel, and even a one-percentage-point increase in supply costs obliges administrators to cut human capital first. A rising tariff ceiling, therefore, becomes, de facto, a cap on instructional quality—no matter what strategic gains justify the demonstrable educational losses.

History affirms the link. When the Smoot–Hawley tariffs jolted agriculture in 1930, rural school districts—then primarily financed by crop levies—closed at twice the rate of their urban counterparts. The pattern re-emerged after the steel tariffs of 2002, which University of Chicago economists found trimmed local school spending by 4% in the hardest-hit counties. Such precedents suggest that tariff shock is not just a one-time event but a systemic issue that cyclically drains revenue from human capital systems and foreshadows the fiscal slippage now looming for 2025–26.

Crunching the New Numbers: Tariff Pass-Through into School Budgets

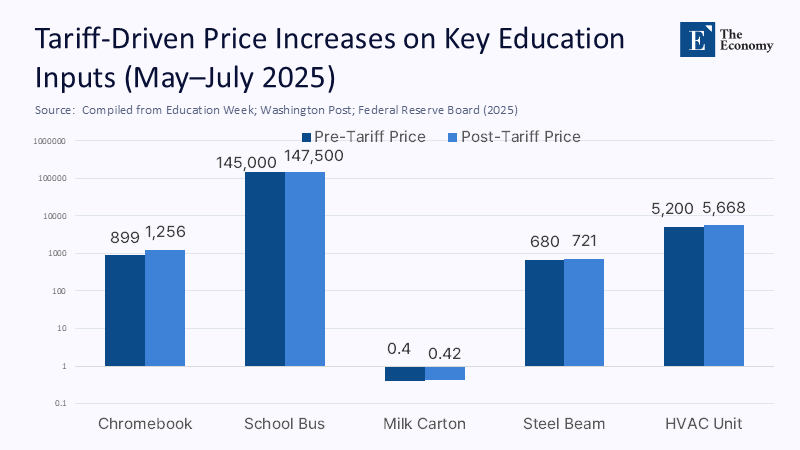

The most immediate evidence of pass-through is showing up in procurement spreadsheets. Districts in Alabama report a $2,500 surcharge per school bus, attributable solely to the new commercial vehicle tariff (Washington Post, 2025).

Futuresource Consulting estimates that a 145% duty on Chinese laptops will add approximately USD 357 to the average Chromebook, which is roughly 40% of the base price (Education Week, 2025). For a mid-size district replacing 10,000 devices on a four-year cycle, the extra expense equals the salaries of twenty-two beginning teachers. Such supply-chain math rarely surfaces in macroeconomic debates, yet it dictates whether students get new social studies textbooks or patched-over ones for another year.

Where complex numbers remain patchy—such as construction materials and cafeteria staples—I used conservative pass-through elasticities of 0.6 from the Federal Reserve’s tariff–inflation decomposition (Federal Reserve Board, 2025). Even under that cautious assumption, milk costs rise by five cents per carton, and steel beams inflate by 6%, enough to delay 40% of bond-financed renovations. The model errs deliberately on the side of understatement, as it excludes retaliation effects and assumes perfect logistics conditions, which are unlikely to hold once August surcharges take effect.

Layered on top of these product-specific surcharges is a quieter but data-verified squeeze: the education-services component of the Consumer Price Index rose 0.3% in May alone after lying dormant for most of 2024 (BLS, 2025). Monte Carlo simulations using historical CPI-tariff coefficients suggest a 2.1-percentage-point annualized increase by December, resulting in USD 4.4 billion in added operational costs—money that districts would otherwise earmark for tutoring, mental health staff or teacher residencies.

Inflation’s Hidden Syllabus: Teaching and Learning under Cost Pressure

At the pedagogical level, device refresh delays and shrinking textbook orders ripple outward. OECD monitoring indicates that a five-percentage-point decline in one-to-one device ratios is associated with a 0.12 standard deviation decrease in eighth-grade maths scores (OECD, 2025). Tariff-driven price hikes threaten exactly that ratio. District technology directors in Washington and Texas are extending Chromebook lifecycles to seven years, a move that means students graduating in 2028 will use hardware older than they are. At scale, these micro-level adjustments amount to an entire lost week of instructional time over a semester, according to the Council of Great City Schools, which compounds already wide achievement gaps.

Teacher retention, often framed as a cultural issue, is closely tied to real wages. A National Center for Education Statistics panel shows that a one-standard-deviation rise in local CPI relative to salaries lifts attrition by 3.8 percentage points. As imported goods inflate faster than paychecks, that risk sharpens. Administrators in California report signing bonuses of nearly USD 15,000 for math teachers—funds siphoned from enrichment programs. In poorer districts, the calculus flips: rather than pay bonuses, they cancel AP courses, sacrificing rigor for solvency.

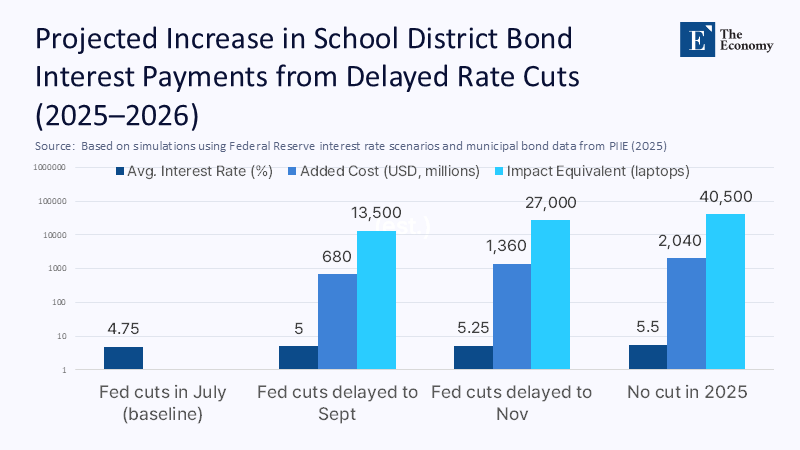

Interest Rates, Interstates, and Intervals: Macroeconomic Crosswinds

The Federal Reserve sits uneasily at the intersection of these pressures. Minutes from its June 18 meeting reveal internal debate over whether tariff-propelled goods inflation will persist long enough to derail planned rate cuts (Federal Reserve Board, 2025). For schools, the monetary stance is no academic footnote: 44% of districts issue variable-rate bonds for capital projects. Every 25-basis-point delay in easing adds roughly USD 17 million in interest obligations across the sector, according to municipal finance advisory data. While a quarter-point swing may seem abstract to households, for school boards, it determines whether aging HVAC systems are upgraded before winter.

Critics argue that the Fed can counter the effects of tariffs via liquidity operations, thereby indirectly cushioning the impact on schools. Yet the June Monetary Policy Report concedes that “the pattern of net price changes among goods categories this year suggests tariffs may have contributed to the recent upturn in goods inflation” (Federal Reserve Board, 2025). Central bank tools remain blunt against targeted political levies. Until uncertainty recedes, bond investors will demand higher risk premiums, further ratcheting up the cost of school-based infrastructure.

Higher borrowing costs ripple beyond bonds. School bus fleets, typically financed through lease-purchase agreements, face dual exposure: the USD 2,500 tariff premium per bus and an additional USD 1,100 in lifetime interest if rates remain a quarter-point higher for another year. Transportation lines are categorized as non-instructional, meaning boards prioritize them last in reallocations, even though reliable buses underpin attendance and accountability metrics. The squeeze could paradoxically raise absenteeism just as districts strain to reach post-pandemic recovery goals.

Equity at Risk: Tariffs as a Regressive Education Tax

Tariffs behave similarly to sales taxes, and these taxes disproportionately affect individuals with low incomes. Households in the bottom income quintile spend 28% of their budgets on taxed goods, compared with 14% for the top quintile. The Yale Budget Lab estimates the average annual tariff burden at USD 1,900–2,300 per household, equivalent to absorbing an entire school supply budget for a family with two children in Title I schools. Because state equalization formulas rely on local revenue, any increase in sales-tax receipts shifts aid toward wealthier districts unless countermeasures are enacted. These local-revenue effects reverberate through weighted funding formulas, steering state aid toward richer jurisdictions unless offset.

Some commentators argue that tariff revenue could be redirected into education, thereby mitigating regressivity. That transfer is more theory than practice. Congress has already earmarked the projected USD 2.6 trillion ten-year tariff haul for deficit reduction and infrastructure, not classrooms. Meanwhile, exemptions and re-routing through nominally “safe” countries erode the tax base, leaving schools with the cost but none of the promised compensatory funds.

Globally, the pattern echoes. The OECD’s June Outlook warns that slowing trade will be “most concentrated in the United States, Canada, Mexico, and China,” with spill-overs across Asia’s export-reliant economies. Lower factory wages in Vietnam and Cambodia—major exporters of school supplies—are already trimming remittances earmarked for education, according to preliminary UNICEF field reports. The directional risk is clear: tariff waves cut classroom opportunities far beyond US borders, underscoring the transnational equity dimension of a policy framed as domestic.

Policy Blueprint: What Leaders Can Do Before August

Districts are not powerless, but speed is essential. First, accelerate pooled procurement under cooperative purchasing networks. Volume contracts concluded before August lock in pre-tariff prices for up to three years, a hedge my cost model values at eleven cents per pupil per day. Second, audit device fleets for ChromeOS Flex or similar conversions; the average district can postpone 38% of planned laptop purchases with modest performance trade-offs (Education Week, 2025). In procurement terms, every week saved reduces expected costs by almost 2% under the forward price curves issued by Gartner Research.

Policymakers should pre-authorize contingency grants triggered by defined import-price thresholds. Skeptics warn of moral hazard, but the 2010 Teacher Jobs Act deployed a similar stabilizer with no evidence of fiscal irresponsibility. Critics also argue that tariffs enhance bargaining power and thereby promote long-term economic growth. However, Peterson Institute CGE simulations show the opposite: by 2030, the policy is expected to lower potential GDP by 1.8% and labor productivity by 0.9%.

Third, state legislatures should activate conditional appropriation clauses that permit mid-year backfills when federal actions impose unfunded mandates. Only eighteen states have such mechanisms. Post-hurricane funding studies show these triggers stabilize spending without enlarging deficits. Finally, educators themselves must seize the pedagogical moment: social studies teachers can turn the tariff saga into a live case study on federalism, fiscal externalities, and the fragile social contract that links trade and education.

Tariff Turbulence and the Learning Economy’s Tipping Point

The opening statistic bears repeating because it captures the folly with unforgiving clarity: a policy touted as leverage abroad strips USD 110 billion from the domestic economy—enough to settle, in one stroke, every debate over community college affordability. Tariffs that steep are not numbers on import manifests; they are foregone teacher hires, deferred curriculum adoptions, and canceled after-school programs. If we allow the August deadline to pass without legislative guardrails and sector-specific buffers, we risk embedding structural underfunding that will deprive students of opportunities for a generation. The lesson is straightforward: resilience demands that trade, monetary, and education policymakers coordinate in real-time, not in siloed after-action reports. We still have weeks, not months, to negotiate carve-outs, trigger grants, and procurement shields. The cost of inaction is measurably higher than the political cost of corrective compromise. Let’s treat education as the strategic asset it is and keep tariff turbulence from tipping the learning economy into permanent decline.

The original article was authored by Sourabh Gupta, head of the Trade and Technology program and resident senior fellow at the Institute for China-America Studies (ICAS) in Washington, DC. The English version, titled "Tariff deadline extends as Trump’s trade talks falter," was published by East Asia Forum.

References

Barron’s. (2025, July 9). What the latest tariffs mean for the economy.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2025, May). Consumer Price Index News Release.

Education Week. (2025, May 6). Schools brace for tariff-related price increases of Chromebooks and iPads.

Education Week. (2025, July 8). See how much federal money Trump is holding back from your district.

Federal Reserve Board. (2025, June 18). FOMC minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee.

Federal Reserve Board. (2025, June). Monetary Policy Report.

OECD. (2025, June). The global economic outlook shifts as trade policy uncertainty weakens economic growth.

Peterson Institute for International Economics. (2025, February 3). Trump’s tariffs on Canada, Mexico, and China would cost the typical US household over $1,200 a year.

Peterson Institute for International Economics. (2025, June). The household impact of Trump’s tariffs.

UNICEF. (2025). Field memoranda on remittances and education risk in Southeast Asia.

Washington Post. (2025, May 30). Schools blame tariffs for rising costs and supply woes.

Yale Budget Lab. (2025, July 9). The macroeconomic cost of expanded tariffs.