[해외 DS] 냄새 예측, 머신러닝으로 한 걸음 더

입력

수정

분자의 화학적 특성에 따라 냄새를 예측하는 모델 개발 50만 개의 분자에 대한 냄새 예측, 인간의 70년 작업량 혼합물 인식은 다음 단계, 조합의 수 증가로 어려움 예상

[해외DS]는 해외 유수의 데이터 사이언스 전문지들에서 전하는 업계 전문가들의 의견을 담았습니다. 저희 데이터 사이언스 경영 연구소 (GIAI R&D Korea)에서 영어 원문 공개 조건으로 콘텐츠 제휴가 진행 중입니다.

사람의 코에 황화수소는 썩은 달걀 냄새를, 제라닐 아세테이트는 장미 냄새를 풍긴다. 하지만 새로운 화학 물질의 냄새를 맡지 않고 어떤 냄새가 날지 추측하는 문제는 식품 과학자, 조향사, 신경 과학자 모두에게 오랫동안 큰 난제였다.

냄새 물질의 화학적 특성과 냄새의 관계, 더욱 명확하게 밝혀 줄 것으로 기대

그러나 최근 발표된 사이언스(Science) 연구에 따르면, 연구자들은 '주요 냄새 지도'(Principal Odor Map)를 개발해 이 문제에 도전했다. 주요 냄새 지도 모델링은 아직 합성된 적이 없는 50만 개의 분자에 대한 냄새를 예측했는데, 이는 인간이 직접할 때 70년이나 걸리는 작업량이다. 이 연구를 공동 주도한 미시간주립대 식품과학자 에밀리 메이휴(Emily Mayhew)는 "전례 없는 분자 프로파일링 속도"라고 강조했다.

빛의 색은 파장으로 정의되지만, 분자의 물리적 특성과 냄새의 관계는 그렇게 단순하지 않다. 미세한 구조적 변화만으로도 분자의 냄새가 크게 달라질 수 있으며, 반대로 분자 구조가 다른 화학물질도 비슷한 냄새를 풍길 수 있다. 그 때문에 이전의 머신러닝 모델은 화학 정보학이라고 불리는 알려진 냄새 성분의 화학적 특성과 냄새 사이의 연관성을 발견했지만, 예측 성능은 제한적이었다.

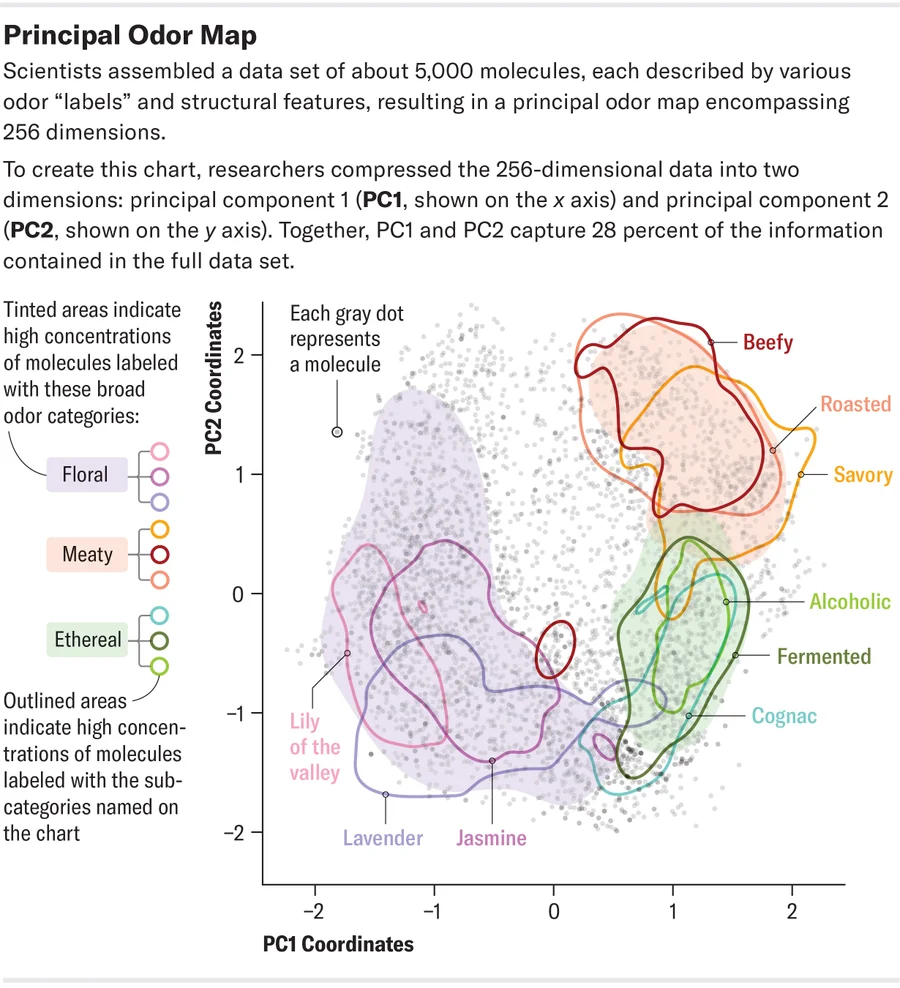

새로운 연구에서 연구진은 5,000개의 이미 알려진 냄새 성분으로 신경망을 훈련해, 분자의 냄새에 영향을 미치는 정도에 따라 256개의 화학적 특징을 강조하도록 했다. 이 연구에 참여하지 않은 IBM Research의 계산생물학자 파블로 메이어 로하스(Pablo Meyer Rojas)는 표준 화학 정보학 대신 "연구진은 자체적인 방법을 사용했다"라며 "그들은 냄새와 관련된 속성을 직접 유추했다"라고 설명했다.

비슷한 냄새 물질 군집화 및 냄새 강도·유사도 예측, "단일 분자에 한함"

이 모델은 화학적 특성에 따라 각 분자의 좌표가 결정되는 거대한 냄새 지도를 생성한다. 또한 '풀 냄새' 또는 '나무 냄새'와 같은 55개의 설명 레이블을 사용하여 각 분자가 사람에게 어떤 냄새가 나는지 예측할 수 있다. 놀랍게도, 비슷한 냄새를 풍기는 냄새 물질이 지도에 군집으로 나타나는데, 이는 이전의 냄새 지도에서는 찾아볼 수 없었던 기능이다.

이어서 연구팀은 모델이 새로운 냄새 물질을 얼마나 잘 예측하는지를 평가하기 위해 15명의 사람의 판단을 기반으로 모델의 예측을 분석했다. 결과적으로, 모델의 예측은 사람의 평균적인 설명과 매우 유사했다. 게다가 모델은 냄새의 강도와 두 분자 간의 냄새 유사도 예측까지 성공했는데, 이는 명시적으로 설계되지 않은 두 가지 기능이라는 점에서 놀라운 발견이었다.

그러나 이 모델은 단일 분자의 냄새만 예측할 수 있다는 한계점이 있다. 향수와 냄새나는 쓰레기봉투가 있는 일상 세계에서 냄새는 종종 다양한 물질의 혼합물이다. 메이휴는 "혼합물 인식은 다음 단계"라며, 가능한 조합의 수가 매우 많기 때문에 혼합물을 예측하는 것은 엄청난 어려움을 겪을 것이지만, "첫 번째 단계는 각 분자가 어떤 냄새를 내는지를 이해하는 것"이라고 메이어 로하스는 설명했습니다.

Machine Learning Creates a Massive Map of Smelly Molecules

Scientists can finally predict a chemical’s odor without having a human sniff it

To a human nose, hydrogen sulfide smells like rotten eggs, geranyl acetate like roses. But the problem of guessing how a new chemical will smell without having someone sniff it has long stumped food scientists, perfumers and neuroscientists alike.

Now, in a study published in Science, researchers describe a machine-learning model that does this job. The model, called the Principal Odor Map, predicted smells for 500,000 molecules that have never been synthesized—a task that would take a human 70 years. “Our bandwidth for profiling molecules is orders of magnitude faster,” says Michigan State University food scientist Emily Mayhew, who co-led the study.

The color of light is defined by its wavelength, but there's no such simple relationship between a molecule's physical properties and its smell. A tiny structural tweak can drastically alter a molecule's odor; conversely, chemicals can smell similar even with different molecular structures. Earlier machine-learning models found associations between the chemical properties of known odorants (called chemoinformatics) and their smells, but predictive performance was limited.

In the new study, the researchers trained a neural network with 5,000 known odorants to emphasize 256 chemical features according to how much they affect a molecule's odor. Rather than using standard chemoinformatics, “they built their own,” says Pablo Meyer Rojas, a computational biologist at IBM Research, who was not involved in the study. “They directly inferred the properties that are related to smell,” he says—although how the model arrives at these predictions is too complex for a human to understand.

The model creates a giant map of odors, with each molecule's coordinates determined by its chemical properties. The model also predicts how each molecule will smell to a human, using 55 descriptive labels such as “grassy” or “woody.” Remarkably, similar-smelling odorants appeared in clusters on the map—a feature prior odor maps couldn't achieve.

The team then compared the model's scent predictions with the judgments of 15 humans trained to describe new odorants. The model's predictions were as close as those of any human judge to the panel's average descriptions of the new scents. It could also predict an odor's intensity and how similar two molecules would smell—two things it was not explicitly designed to do. “That was a really cool surprise,” Mayhew says.

The model's main limitation is that it can predict the odors of only single molecules; in the real world of perfumes and stinky trash bags, smells are almost always olfactory medleys. “Mixture perception is the next frontier,” Mayhew says. The vast number of possible combinations makes predicting mixtures exponentially more difficult, but “the first step is understanding what each molecule smells like,” Meyer Rojas says.