[해외 DS] 수학적으로 완벽한 선거 시스템을 설계할 수 있을까?

입력

수정

선호투표제는 '스포일러 효과'를 완화하고 유권자의 의사를 더 효과적으로 반영 그러나 어떤 순위 선택 투표 방식도 완벽하지 않고 직관에 반하는 결과도 초래해 후보자에 점수를 매기는 카디널 투표도 선거 시스템의 개선 방안이 될 수 있어

[해외DS]는 해외 유수의 데이터 사이언스 전문지들에서 전하는 업계 전문가들의 의견을 담았습니다. 저희 데이터 사이언스 경영 연구소 (GIAI R&D Korea)에서 영어 원문 공개 조건으로 콘텐츠 제휴가 진행 중입니다.

제3당 대선 후보들은 종종 주요 정당 중 하나의 표를 '훔쳐서' 선거를 망친다는 비난을 받곤 한다. 하지만 사회 선택 이론(social choice theory)의 수학적 접근을 통해 선거 시스템을 개선할 수 있는 여지가 있다.

역사적으로 박빙의 승부를 펼쳤던 고어 대 부시 미국 대통령 선거에서 랠프 네이더의 녹색당이 민주당 성향의 진보 표를 상당히 잠식한 것으로 분석됐었다. 불과 수천 표 차이로 재검표까지 실시했던 플로리다주에서 랠프 네이더가 수만 표를 얻어 결과적으로 민주당 지지자들로부터 부시 당선의 일등 공신, 선거 훼방꾼이라는 비난을 듣기도 하였다.

선호투표제의 투표 집계 방식과 각각의 예외성

사회 선택 이론가들은 '선호투표제'가 위의 스포일러 효과를 완화하는 동시에 유권자들이 투표에서 더 많은 목소리를 낼 수 있는 대안적인 선거 시스템이라고 제안했다. 선호투표제는 몇 가지 분명한 장점이 있다. 그러나 경제학의 오래된 정리에 따르면 선호투표제를 사용하려는 모든 시도는 직관에 반하는 결과를 동반할 가능성이 존재한다.

선호투표제는 단일 후보에게만 투표하는 것이 아니라 선호도 순으로 후보의 순위를 매길 수 있다. 따라서 네이더를 지지하고 싶지만, 고어의 표도 지키고 싶은 유권자는 고어를 2순위로 선택할 수 있다. 네이더가 충분한 표를 얻지 못해 떨어지더라도 고어가 2위를 차지하면 선거에서 여전히 유리할 수 있다. 또한 선호투표제의 지지자들은 순위 투표가 악의적인 진흙탕 싸움을 자초하는 선거 전략을 막을 수 있다고 주장한다. 그 이유는 일반적인 선거와 달리 순위 선택 경선에서는 후보자 1등을 주지 않을 유권자까지 포함한 모든 유권자에게 어필해야 하기 때문이다. 현재 메인주와 알래스카주는 대통령 예비선거를 포함한 모든 주와 연방 선거에 선호투표제를 도입하여 여러 후보자가 같은 유권자에게 어필할 기회를 제공하고 있다.

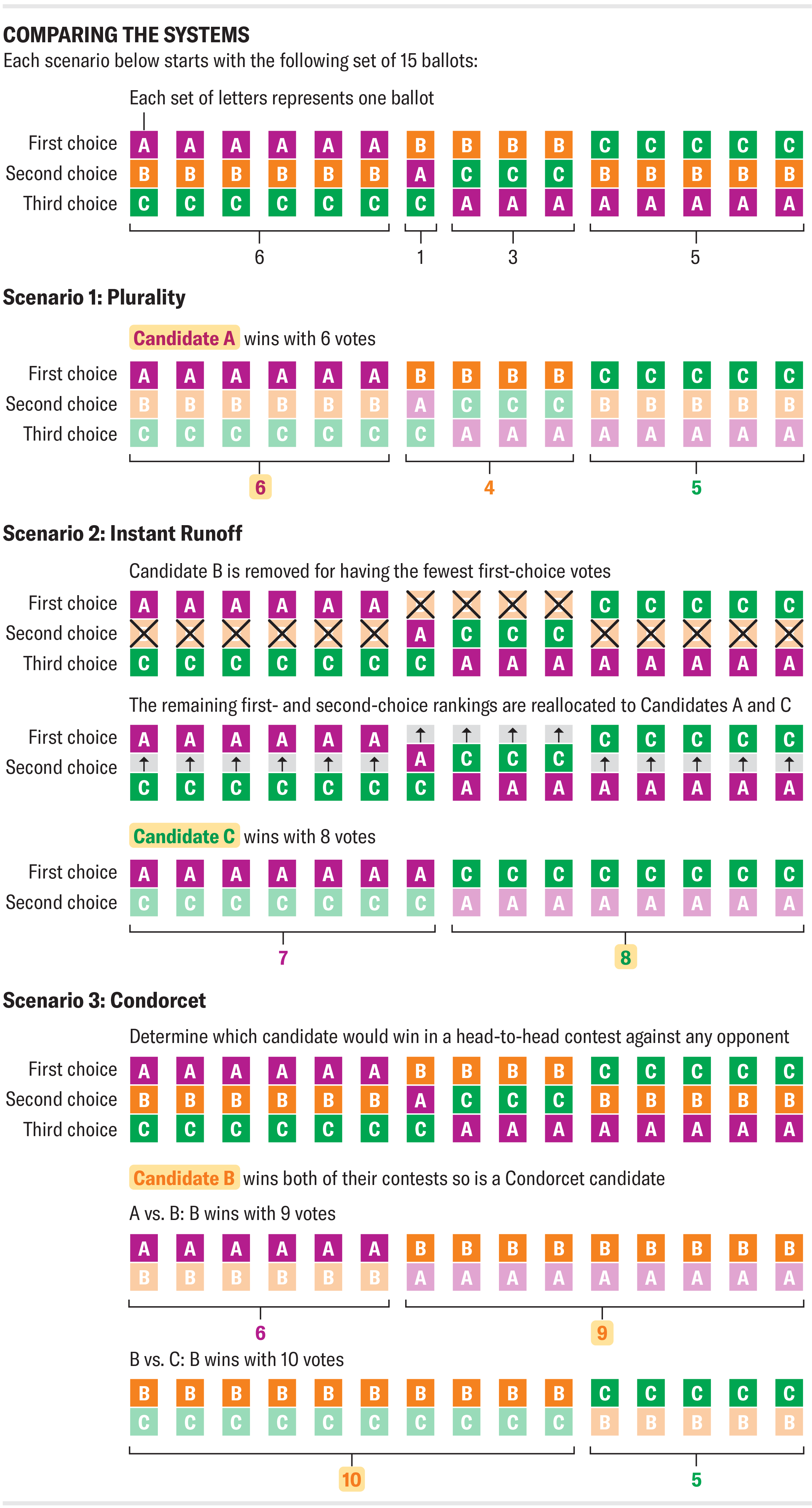

유권자가 후보자 순위를 매긴 후 해당 정보가 어떻게 집계되어야 한 명의 당선자가 결정될까? 그 답은 생각만큼 간단하지 않으며, 여러 가지 방법이 제안됐다. 투표 집계에 대한 세 가지 접근 방식인 상대다수결, 즉시결선, 그리고 콩도르세 방식을 살펴보고 각 방식에 따라 어떤 예상치 못한 결과가 나올 수 있는지 알아보자.

즉시 결선 투표 및 콩도르세 방식과 달리, 상대다수결 방식은 실제로 미국에서 가장 일반적인 투표 방식이며, 1순위 표를 가장 많이 얻은 사람이 당선된다. 하지만 제3당의 선거 스포일러 문제 외에도, 후보자 A가 34%를 득표하고 후보자 B와 C가 각각 33%를 득표했다고 가정했을 때, 다른 모든 유권자의 마지막 선택을 받았더라도 A 후보가 과반수 득표로 당선되는 문제점이 있다. 따라서 상대다수결은 투표를 낭비하고 유권자의 다양한 선호를 무시하는 결과를 낳는다.

이보다 더 나은 방법(그리고 미국에서 시행되는 선호투표제와 오스카 시상식에서 최고의 영화를 선정하는 데 사용되는 방법)은 즉시결선투표입니다. 1순위 득표의 과반수를 얻은 후보가 없는 경우, 1순위 득표가 가장 적은 후보가 고려 대상에서 제외되고 유권자의 다음 선택에 따라 표가 재할당된다(예: 세 후보의 순위가 1위 B, 2위 C, 3위 A이고 1순위 득표가 가장 적은 C 후보가 탈락하는 경우, C의 공백을 메우기 위해 A가 투표용지에서 위로 올라가 1위 B, 2위 A가 된다). 1순위 득표수가 가장 적은 후보를 제거하는 과정은 한 후보가 과반수를 차지할 때까지 반복된다. 즉시결선투표는 상대다수결에 비해 투표 낭비가 적지만, 그 자체로 단점이 있다. 선호하는 후보가 더 많은 1순위 표를 얻으면 패배할 가능성이 더 높은 기이한 상황이 발생할 수 있기 때문이다.

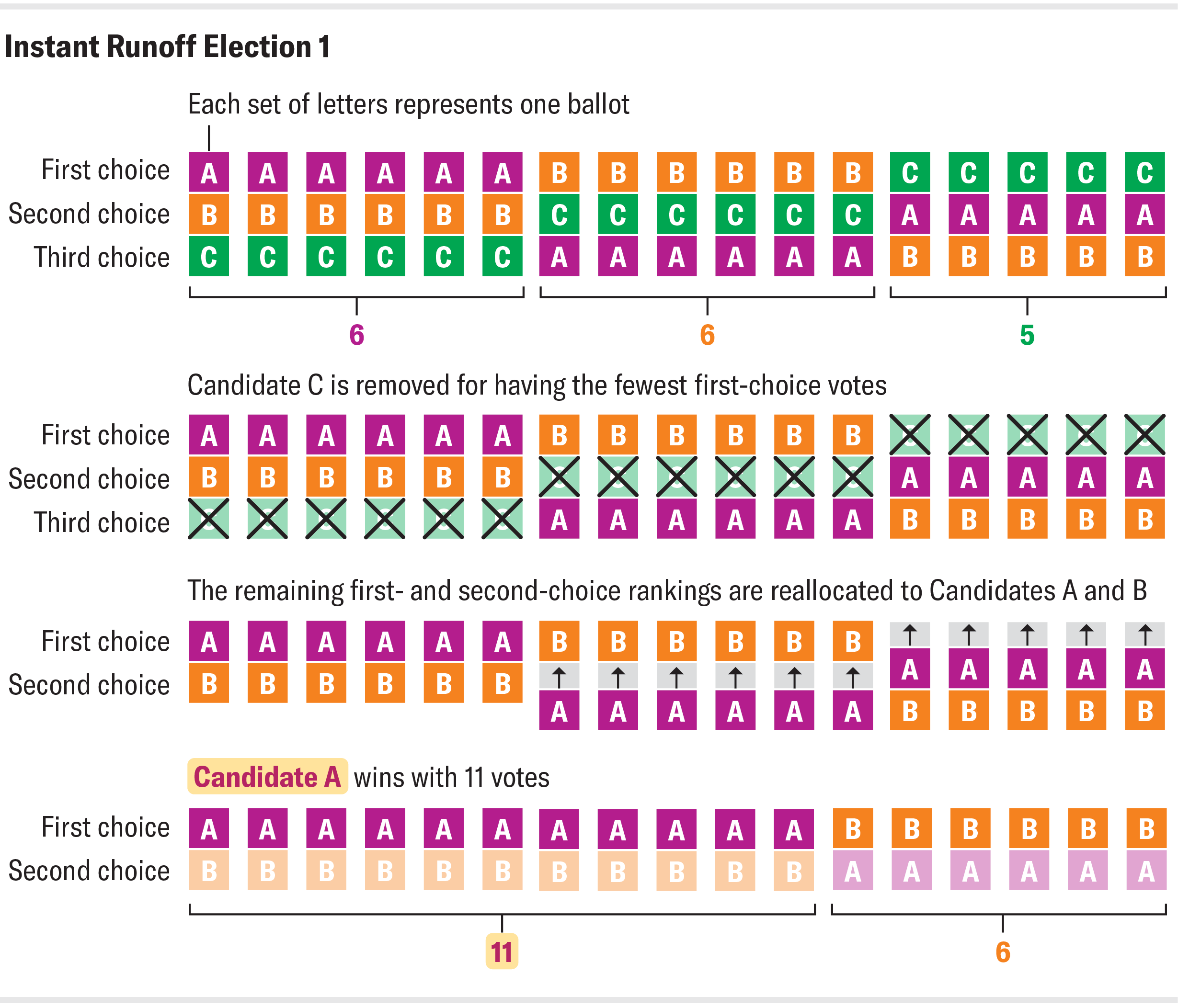

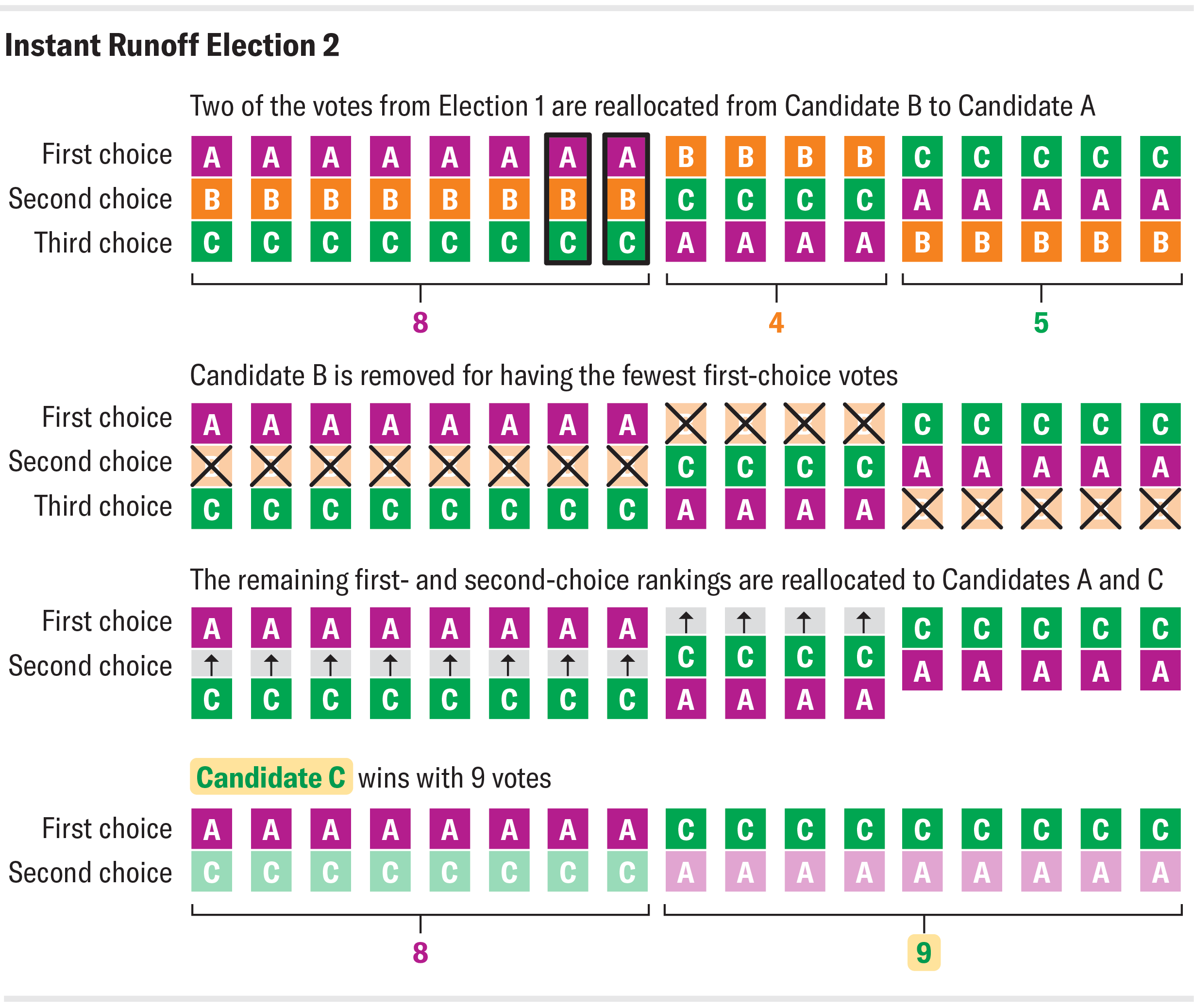

아래 그림(electionscience.org의 예시를 기반으로 함)은 위의 시나리오를 잘 보여준다. 선거 1이라고 하는 가상의 즉시결선선거에서 후보자 A가 승리한다. A와 B의 1순위 득표수는 같지만, 어느 쪽도 당선에 필요한 과반수(17표 중 9표)를 얻지 못했다. 따라서 1순위 득표수가 가장 적은 C는 경합에서 제외되고, C의 부족한 표를 채우도록 투표용지가 조정되어 A 후보가 과반수를 차지하게 된다.

이제 선거 2라는 별도의 시나리오를 상상하자. 선거 1과 같은 방식으로 모든 사람이 투표하고, A를 세 번째 선택에서 첫 번째 선택으로 업그레이드한 두 사람을 제외하고는 투표 순위가 동일하다. 하지만 놀랍게도 A가 이전보다 더 많은 1순위 표를 얻었음에도 C가 새로운 승자로 등극했다. A를 업그레이드하면 B가 다운그레이드되어 B가 가장 적은 1순위 표를 얻은 후보가 되기 때문이다. B가 제거되면 A는 선거 1에서 B와 맞붙었을 때처럼 C와의 대결에서 유리한 고지를 점하지 못하는 상황이 연출된다.

이러한 반직관적인 현상은 2009년 버몬트주 벌링턴의 시장 선거에서 진보당 소속의 밥 키스(Bob Kiss) 후보가 공화당과 민주당 후보를 이긴 사례에서 볼 수 있다. 더 많은 유권자가 키스를 1순위로 선택했다면 그는 즉시결선선거에서 패배했을 것이다.

18세기 프랑스 수학자이자 정치 철학자인 마르퀴스 드 콩도르세(Marquis de Condorcet) 후작의 이름을 딴 콩도르세 방식은 다른 후보와 일대일 대결에서 이길 수 있는 후보를 선출하는 방식이다. 예를 들어, 제삼의 후보가 없는 선거에서 앨 고어가 2000년에 조지 W. 부시를 이겼을 것이라고 가정하면 고어는 제삼자 후보 중 한 명과의 일대일 대결에서도 분명히 승리했을 것이다. 고어가 가상의 일대일 선거에서 모두 승리한다면 그는 콩도르세 후보다. 국민이 모든 상대 후보보다 고어 후보를 선호하기 때문에 그런 후보가 승자가 되는 것은 당연해 보인다. 하지만 콩도르세 후보를 선출하는 데 있어 큰 장애물이 하나 있다. 유권자 선호도는 순환적일 수 있는데 A를 B보다 선호하고 B를 C보다 선호하지만, 또한 C를 A보다 선호할 수도 있다는 설명이다. 이러한 전이성 위반을 콩도르세 역설이라고 부른다.

아래 그림은 앞서 논의한 세 가지 시스템에서 각각 다른 결과를 낳는 선거를 나열했다. 완벽한 순위 선택 투표 시스템이 존재하지 않는 것처럼 보인다. 어쩌면 우리는 기존 제안의 함정을 피하면서 대중의 이익을 최대한 대변하는 이상적인 설계를 아직 발견하지 못했을지도 모른다.

선호투표제의 증명된 한계와 대안

노벨 경제학상을 수상한 경제학자 케네스 애로(Kenneth Arrow)는 이 문제를 연구한 결과, 투표자 순위를 하나의 사회적 순위로 변환하는 합리적인 집계 방법의 최소 요건을 제시했다:

- 만장일치: 인구의 모든 사람이 후보자 A를 후보자 B보다 높은 순위를 매긴다면 집계자는 후보자 A를 후보자 B보다 높은 순위에 놓아야 한다.

- 무관한 선택대상으로부터의 독립: 집계 자가 후보자 A를 후보자 B보다 위에 배치한다고 가정한다. 유권자가 순위를 일부 변경했지만, 모든 사람이 A와 B의 상대적 순위를 동일하게 유지한다면, 새로운 집계 순위에서 A는 B보다 위에 유지되어야 한다. A와 B의 사회적 순서는 다른 후보의 순서가 아닌 A와 B의 개별 순서에만 의존해야 한다.

애로는 이 두 가지 조건을 모두 만족하는 집계자는 오직 한 가지 유형, 즉 독재체제뿐이라는 '애로의 불가능 정리'로 알려진 놀라운 사실을 증명해 냈다. 여기서 독재형 집계란 같은 단일 투표자의 순위를 항상 모방하는 터무니없는 집계 방식을 의미한다. 독재가 아니라면 아무리 영리하고 복잡한 순위 선택 투표 방식이라도 만장일치와 무관한 선택대상으로부터의 독립을 동시에 만족시킬 수는 없다는 것이다. 이 정리는 어떤 선호투표제 방식도 완벽할 수 없으며, 항상 직관에 반하는 결과와 싸워야 한다는 것을 시사한다.

하지만 애로의 정리가 선호투표제를 폐기해야 한다는 것을 의미하지 않는다. 선호투표제는 여전히 다수결 투표보다 유권자의 의사를 더 많이 반영한다. 단지 집계에 원하는 속성을 골라서 선택해야 하며, 모든 속성을 다 가질 수 없다는 것을 인정해야 한다는 의미다. 이 정리는 모든 선거에 결함이 있다는 것이 아니라, 어떤 선호투표 시스템도 결함에서 벗어날 수 없다는 것을 말한다. 애로는 자신의 결과에 대해 이렇게 말했다 "대부분 시스템이 항상 나쁘게 작동하는 것은 아니다. 제가 증명한 것은 모든 시스템이 때때로 나쁘게 작동할 수 있다는 것이다."

한편 선호투표제만이 선거 시스템을 개선할 수 있는 유일한 방법은 아니다. 단순히 후보자 순위를 매기는 것만으로는 유권자의 선호도에 대한 많은 정보를 얻을 수 없다. 예를 들어 가장 먹고 싶은 음식의 순위를 바닐라 아이스크림 > 초콜릿 아이스크림 > 운동화 순으로 나열해 보면, 이 순위는 내가 바닐라 아이스크림과 초콜릿 아이스크림을 얼마나 좋아하는지, 운동화를 얼마나 싫어하는지에 대한 정보를 전달하지 않기 때문이다. 선호도를 제대로 표현하려면 후보 음식에 점수를 매겨 내가 어떤 음식을 더 선호하는지뿐만 아니라 얼마나 선호하는지 알려야 한다. 이를 카디널 투표 또는 범위 투표라고 하는데, 만병통치약이 아니며 단점도 있지만 순위 선택 투표에만 적용되는 애로의 불가능 정리의 한계를 우회할 수 있다.

많은 사람이 카디널 투표에 익숙하다. 올림픽 심사위원들이 참가자들에게 숫자로 점수를 매겨 최종적으로 총점이 가장 높은 사람을 우승자로 결정하는 방식과 같다. 온라인에서 소비자의 별점을 기준으로 제품을 정렬할 때마다 카디널 선거의 우승자가 표시된다. 고대 스파르타 사람들은 집회에 모여 각 후보를 차례로 외치는 방식으로 지도자를 선출했는데 가장 큰 함성을 받은 사람이 선거에서 승리했다. 현대인의 귀에는 투박하게 들리지만, 사실 이 방식은 초기 형태의 카디널 투표였다. 사람들은 여러 후보자에게 투표하고 군중들의 함성소리에 기여할 수 있는 목소리 크기를 선택해 '점수'를 매긴 것이다. 카디널 투표는 지금까지 논의한 다른 어떤 시스템보다 더 많은 의견을 제시할 수 있음에도 불구하고 현대 선거에서 사용된 적이 없다는 점을 고려하면 의아하다.

Could Math Design the Perfect Electoral System?

Graphics reveal the intricate math behind ranked choice voting and how to design the best electoral system, sometimes with bizarre outcomes

Third-party presidential candidates are often blamed for ruining an election for one of the major political parties by “stealing” votes away from them. But with a little help from the math of social choice theory, elections could embrace the Ralph Naders of the world.

Take the historically tight Gore vs. Bush U.S. presidential election in 2000, when Americans anxiously awaited the resolution of legal battles and a recount that wouldn’t reveal a winner for another month. At the time the Onion published the headline “Recount Reveals Nader Defeated.” Of course Ralph Nader was never a serious contender for office. This led many to suggest that the Green Party candidate, like other third-party politicians, had attracted enough votes away from one of the two major parties to tip the scales against them (in this case the Democrats, who lost the election by just 537 votes).

Ranked choice voting is an alternative electoral system that would mitigate the spoiler effect while giving voters more voice to express themselves at the polls, social choice theorists suggest. Ranked choice voting boasts some obvious advantages. The mathematical discussion over how best to implement it, however, is surprisingly subtle. And an old theorem from economics suggests that all attempts to use ranked choice voting are vulnerable to counterintuitive results.

Rather than voting only for a single candidate, ranked choice voting allows people to rank the candidates in order of preference. This way, if somebody wanted to support Nader but didn’t want to take away a vote from Gore, they could have ranked Gore second at the voting booth. When Nader didn’t amass enough votes, the second place ranking for Gore would still benefit him in the election. Proponents also contend that ranked choice voting disincentivizes vicious mudslinging campaign tactics. That’s because, unlike in typical elections, candidates in ranked choice races would need to appeal to all voters, even those who wouldn’t give them a top spot on the ballot. Currently Maine and Alaska have instituted ranked choice voting for all state and federal elections, including presidential primaries, in which it’s more likely for multiple candidates to appeal to the same voters.

Once voters have ranked candidates, how does that information get aggregated to reveal a single winner? The answer is not as straightforward as it might seem, and many schemes have been proposed. Let’s explore three approaches to vote tallying: plurality, instant runoff and “Condorcet methods,” each of which leads to unexpected behavior.

Unlike instant runoff and Condorcet methods, plurality is not actually a ranked choice voting scheme. In fact, it’s the most common voting method in the U.S.: whoever gains the most first-choice votes wins the election. Plurality can come with unfavorable outcomes. In addition to the problem of third-party election spoilers, imagine if candidate A received 34 percent of the votes, and candidates B and C each received 33 percent. Candidate A would win the plurality even if they were the last choice of every other voter. So 66 percent of the population would have their last pick for president. Plurality wastes votes and ignores the full spectrum of voter preferences.

A better method (and the one used in American implementations of ranked choice voting as well as to select the best picture at the Oscars) is called instant runoff. If no candidate receives more than half of the first-choice votes, then the candidate with the fewest first-choice votes is removed from consideration and their votes get reallocated according to voters’ next choices (e.g., if your ranking of three candidates was 1) B, 2) C, 3) A, and candidate C gets removed for having the fewest first-choice votes, then A will get bumped up in your ballot to fill C’s gap: 1) B, 2) A). The process of removing the candidate with fewest first-choice votes repeats until one candidate has a majority. While instant runoff wastes fewer votes than plurality, it has drawbacks of its own. Bizarre situations can arise where your favorite candidate is more likely to lose if they get more first-choice votes.

The figure below (based on an example from electionscience.org) depicts this scenario. In a hypothetical instant runoff election, called Election 1, candidate A wins. Although A and B have the same number of first-choice votes, neither has the majority required to win (nine out of 17 votes). So C, having the fewest first-choice votes is removed from contention, and the ballots are adjusted to fill C’s gaps, yielding a majority for candidate A.

Now imagine a separate scenario called Election 2, where everybody votes in the same way as in Election 1 except for two people who upgrade A from their third choice to their first choice. Amazingly, even though A won Election 1 and now has more first-choice votes than before, C becomes the new victor. This is because upgrading A results in downgrading B so that B is now the candidate with the fewest first-choice votes. When B is removed, A doesn’t fare as well in a head-to-head against C as they did against B in Election 1.

This counterintuitive phenomenon occurred in Burlington, Vt.’s 2009 mayoral election where Progressive Party member Bob Kiss beat the Republican and Democratic nominees in an instant runoff election. Amazingly, if more voters had placed Kiss first in their ranking, he would have lost the election.

Condorcet methods, named after 18th-century French mathematician and political philosopher Marquis de Condorcet, elect a candidate who would win in a head-to-head election against any other candidate. For example, suppose that in an election without any third-party candidates Al Gore would have beaten George W. Bush in 2000. Gore certainly would have won head-to-head contests with any one of the third-party candidates as well. Gore winning any hypothetical one-on-one election would make him a so-called Condorcet candidate. It seems obvious that such a candidate should be the victor because the population prefers them to all of their opponents. But here’s an important snag in electing Condorcet candidates: they don’t always exist. Voter preferences can be cyclic such that the population prefers A to B and B to C but also prefers C to A. This violation of transitivity is known as the Condorcet paradox (and is reminiscent of intransitive dice, which I wrote about recently).

Several other schemes for amalgamating ranked votes into a winner have been proposed. They each have their pros and cons, and, even more unsettling, the outcome of an election can entirely depend on which system gets used.

The figure shows a simple election yielding different results under each of the three systems we’ve discussed. This comparison leads to a hopeful question: Is there a perfect ranked-choice voting system? Perhaps we just have yet to discover the ideal design that maximally represents the interest of the public while avoiding the pitfalls of existing proposals. Nobel Prize–winning economist Kenneth Arrow investigated this question and came up with bare minimum requirements of any reasonable aggregator, or method that converts voter rankings into one societal ranking:

- Unanimity: If every person in the population ranks candidate A above candidate B, then the aggregator should put candidate A above candidate B.

- Independence of irrelevant alternatives: Suppose the aggregator puts candidate A above B. If voters were to change some of their rankings but everybody kept their relative order of A vs. B the same, then A should remain above B in the new aggregate ranking. The societal ordering of A and B should depend only on individual orderings of A and B and not those of other candidates.

The commonsensical list sets a low bar. But Arrow proved a striking fact that has come to be known as Arrow’s impossibility theorem: there is only one type of aggregator that satisfies both conditions, a dictatorship. By a dictatorship, Arrow means a ridiculous aggregator that simply always mimics the rankings of the same single voter. No ranked choice voting scheme, regardless of how clever or complex it is, can simultaneously satisfy unanimity and independence of irrelevant alternatives unless it’s a dictatorship. The theorem suggests that no ranked choice voting scheme is perfect, and we will always have to contend with undesirable or counterintuitive outcomes.

This proof doesn’t mean that we should scrap ranked choice voting. It still does a better job at capturing the will of the electorate than plurality voting. It simply means that we need to pick and choose which properties we want in our aggregator and acknowledge that we can’t have it all. The theorem doesn’t say that every single election will be flawed, but rather that no ranked-choice electoral system is invulnerable to flaws. Arrow has said of his own result: “Most systems are not going to work badly all of the time. All I proved is that all can work badly at times.”

And the idealists among us should not lose hope, because ranked choice voting isn’t the only game in town for souped-up electoral systems. Merely ranking candidates loses a lot of information about voter preferences. For example, here’s a ranking of foods I’d like to eat from most desirable to least: vanilla ice cream > chocolate ice cream > my own sneakers. The ranking conveys no information about just how close my taste for vanilla and chocolate ice cream is nor my distaste for my Nikes. To properly express my desires, I should assign scores to the candidate meals to communicate not only which ones I prefer more but by how much. This is called cardinal voting, or range voting, and although it’s no panacea and has its own shortcomings, it circumvents the limitations imposed by Arrow’s impossibility theorem, which only applies to ranked choice voting.

We’re all familiar with cardinal voting. In Olympic gymnastics, judges decide the winner by giving numeric scores to the competitors, and whoever has the most total points at the end wins. Whenever you sort products by consumers’ star ratings online you’re presented with the winners of a cardinal election. Ancient Spartans elected leaders by gathering in an assembly and shouting for each of the candidates in turn. Whoever received the loudest shouts won the election. While this sounds crude to modern ears, it was actually an early form of cardinal voting. People could vote for multiple candidates and “score” them by choosing what volume of voice to contribute to the roar of the crowd. This is impressive considering that cardinal voting, despite granting the people more input than any of the other systems we’ve discussed, has never been used in a modern election. Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised: the ancient Greeks did invent democracy after all.