[해외 DS] 샌드아트와 수학의 만남, 일시적인 예술의 영원한 이야기 (1)

입력

수정

바누아투, 다양한 언어와 문화로 구성된 군도 유네스코가 인정한 무형 유산, 모래 그림 민족수학자의 연구로 수학적 모델 발견

바누아투는 83개의 섬으로 이루어진 군도로, 약 315,000명의 다양한 인구가 거주하고 있다. 이 나라는 138개의 방언을 사용하는 세계에서 가장 높은 언어 다양성을 자랑한다. 학교에서 가르치는 두 가지 공식 언어는 프랑스어와 영어다. 바누아투에서 사용되는 앵글로-멜라네시아 피진어인 비슬라마 또는 비클라마가 공용어다.

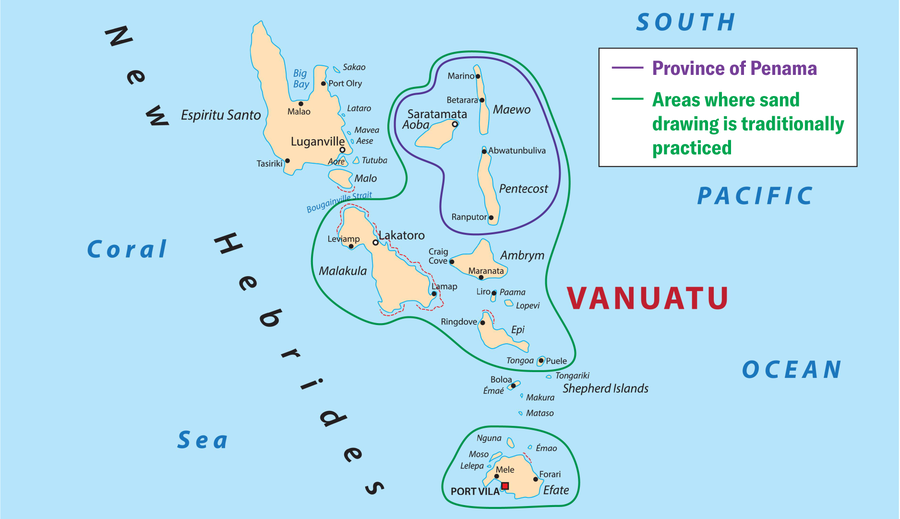

문화는 바누아투의 북부와 남부, 심지어 같은 섬 내에서도 다양하다. 예를 들어 모래 그림은 일부 중부 섬에서만 널리 퍼져 있다. 이 전통은 인도 타밀나두의 흙에 그림을 그리는 것을 연상시키지만 여러 가지 면에서 독특하며, 2008년 유네스코는 바누아투의 모래 그림을 인류무형문화유산으로 분류했다.

바누아투의 '한붓그리기', 수학적 특성 공유해

민족수학자(Ethnomathematician) 알반 다 실바는 2018년 매오섬과 2019년 펜테코스트섬에서 실시한 두 차례의 현장 조사를 기반으로 샌드드로잉의 수학적 모델을 개발했다. 특히 펜테코스트섬 북부의 라가 지역('라라'로 발음)의 사람들이 그린 그림에 초점을 맞췄다. "이 섬들은 아오바섬과 함께 페나마 지방을 구성하고 있으며 공통된 전통을 가지고 있어 연구에 큰 도움이 되었다"라고 실바는 말했다. 실제로 수학적 언어는 샌드드로잉 작업을 설명하는 데 적합한 것으로 밝혀졌으며, 모래 그림을 통해 바누아투 사회가 환경과 관계 맺는 방식을 이해하는 데 도움이 될 수 있다고 덧붙였다.

비슬라마에서 알려진 샌드드로잉은 수천 년의 역사가 있다. 전통적으로 샌드드로잉은 흙이나 모래사장, 재가 쌓인 곳에 손가락으로 연속적인 닫힌 선을 그리는 예술 작품이다. '연속'과 '닫힌'이라는 단어는 수학에서와 같은 의미로, 모래에 그리는 선은 평면의 닫힌 연속 곡선과 유사하다. 이렇게 그려진 선은 선 또는 점으로 구성된 복합 그리드에 의해 제약을 받는다. 그리드는 직사각형 또는 원형일 수 있다. 얼마나 많은 디자인이 사용되고 있는지 알기는 어렵지만, 시간이 지남에 따라 새로운 디자인이 나타나고 안 쓰는 디자인은 사라진다. 지적 재산에 가까운 시스템이 도면을 보호하고 있으므로 이 전통 지식에 대한 접근은 때때로 민감하고 까다롭다.

자연의 언어를 담은 문양, 한 폭의 수학적 추상화

모래 그림은 스토리를 담고 있다. 동물, 곤충, 식물의 상징적인 그림은 해당 사회의 신념, 우주관, 사회 조직, 심지어 전통과도 밀접하게 연관되어 있는데, 이러한 그림은 '카스톰'(kastom)이라는 일반적인 이름으로 함께 묶인다. 또한 바누아투 중부 사회의 윤리적 또는 정치적 내러티브를 이해하는 힌트가 되기도 한다. 많은 경우, 각 그림에는 이러한 다양한 측면과 관련된 토속적인 이름이 붙어 있다.

오늘날 이 사회에서는 이러한 관행을 사람들이 의식, 종교 및 환경 지식을 기억하는 데 도움이 되는 전통적인 그래픽 아트로 인식하고 있다. 또한 라가 지역에서 만난 추장 지프 토달리는 예술가들이 대변인이라고 설명했다: "투투라니(백인 외국인)가 도착하기 전, 북부 펜테코스트 사람들은 말할 줄 몰랐다. 그들은 손가락으로 땅바닥을 따라 그린 그림으로 자신을 표현했었다. 사람 대신 바위, 돌, 언덕과 계곡의 땅, 바람, 비, 바다의 물이 말을 했지만, 이제는 상황이 바뀌었다. 말하는 것은 사람들이고 땅과 바람과 비와 바다는 침묵하고 있다. 이제 라가 지역 사람들은 땅이 더 이상 스스로를 대변할 수 없으니, 우리가 땅을 대변해야 한다'라고 말했다.

샌드드로잉은 완성된 작품이 잠시 후 사라지는 일시적인 예술로, 이는 스토리텔링에 감정을 자극한다. 예술가들은 그림을 그리면서 이야기를 전달하며, 특히 재능 있는 사람들은 그림을 그리면서도 동시에 이야기를 전달할 수 있다. 익숙한 장소, 인물, 동물 또는 심지어 채소 등 역사와 관련된 세부 사항을 그림에 추가하여 관객들의 상상력을 자극하기도 한다. 작품의 일시적인 특성이라는 측면에서 더 깊은 감동을 선사하는 효과가 있다.

[해외 DS] 샌드아트와 수학의 만남, 일시적인 예술의 영원한 이야기 (2)로 이어집니다.

An Ancient Art Form Topples Assumptions about Mathematics

The sand drawings of Vanuatu follow principles from a branch of mathematics known as graph theory

In October 2015 my time training mathematics teachers at a French high school in Port Vila, Vanuatu, was coming to an end. The principal invited me to share kava, a traditional drink in the country. As every social scientist in Vanuatu discovers, sharing kava is a fruitful opportunity for learning. This beverage, which is made from the roots of a tree of the same name, relaxes the drinker and loosens the tongue.

This first encounter with kava was also my introduction to sand drawing. That evening, one of the trainees took out a large board covered with very fine sand. After carefully flattening the surface, he drew a grid of horizontal and vertical lines. Then he began tracing furrows in the sand without ever lifting his finger. When the artist finished, he explained in the language Bislama, “Hemia hem i wan fis i ronwe i stap unda ston from i kat wan sak,” meaning “It is a fish that hides under a stone to escape the shark.”

The fluidity of the line, mixed with the effects of kava, plunged me into a state of wonder. The technique reminded me of the classic challenge to draw a complex figure with a single stroke, without lifting one’s pen or going over the same line twice. It also called to mind a “Eulerian graph” in mathematics, which involves a trail that traverses every edge exactly once while starting and ending at the same point.

As I considered these ideas, an intern approached me and whispered, “Where is the mathematics in this drawing, teacher?” Though he could not have known it, that remark would go on to shape the next six years of my life, including my doctoral work on sand drawing. One question particularly inspired me: How were such drawings created?

My investigation took me further than I could have imagined. By watching expert sand artists, learning about their methods, collecting drawings and history and exploring the work of 20th-century ethnologists, I have developed a mathematical model of sand drawing. My work shows that these artworks can be modeled as the result of algorithms and operations of an algebraic nature. Indeed, mathematical language turns out to be appropriate for describing the work of sand drawing experts. Furthermore, sand drawing can help us understand the relationships that Vanuatu societies maintain with their environment.

A Traditional Art

Vanuatu is an archipelago with a population of some 315,000 people spread throughout 83 islands. The country has the highest linguistic density in the world, with 138 vernacular languages. The two official languages taught in school are French and English. Bislama, or bichlamar, an Anglo-Melanesian pidgin used in Vanuatu, is the common language.

Cultures vary in the north and south of the country and even within the same island. The sand drawing practice is widespread only in some central islands, for example. Although the tradition is reminiscent of drawings done on soil in Tamil Nadu, India, it is unique in many ways. In 2008 UNESCO classified the sand drawing of Vanuatu as part of the intangible cultural heritage of humanity.

My research is based on two field surveys that were conducted on Maewo Island in 2018 and Pentecost Island in 2019 and that particularly focused on drawings made by people in the Raga region (pronounced “Ra-ra”) on northern Pentecost Island. These islands, along with Aoba Island, constitute the province of Penama and are bound by common traditions, which greatly facilitated my research.

“Sand drawing,” or sandroing, as it is known in Bislama, is probably thousands of years old. Traditionally, it consists of a person drawing a continuous, closed line with their finger in beaten earth, sand beaches or ashes. (The words “continuous” and “closed” have the same meaning here as in mathematics: a drawing in the sand is similar to the closed continuous curve of a plane.) This drawn line is constrained by a composite grid of lines or dots. The grid can be rectangular or circular.

Although it is difficult to know how many designs are in use, it is clear that, over time, new ones appear, and others disappear. A system very close to intellectual property protects these drawings, making access to this traditional knowledge sometimes sensitive and challenging.

These artworks are multidimensional in their significance. Some iconic drawings of animals, insects or plants are closely linked with the beliefs, cosmogonies, social organization or even traditions of these societies—which are grouped together under the generic name of kastom. The drawings can also support narratives; they reveal the ethical or political dimensions of societies in central Vanuatu. In many cases, each design bears a vernacular name related to these different aspects.

Today these societies recognize this practice as a traditional graphic art that helps people recall ritual, religious and environmental knowledge. In addition, Jief Todali, a chief whom I met in the Raga region, explained to me that the artists are spokespeople: “Before the arrival of the tuturani [the white foreigners], the people of northern Pentecost did not know how to speak. They expressed themselves through drawings that they traced on the ground with their fingers. Instead of people, the rocks, the stones, the ground of the hills and valleys, the wind, the rain, the water of the sea spoke. But now the situation is reversed. It is the people who speak, and the earth, the wind, the rain and the sea are silent. Now [the people from the Raga region] sometimes say, ‘We have to speak for the land because it can no longer speak for itself.’”

Finally, this ephemeral art—each drawing is erased once it is finished—stimulates storytelling. Practitioners generally pair their drawings with the telling of a tale, and the most gifted ones are able to do this while drawing. It is not uncommon for them to appeal to the imagination of spectators by adding details related to their history, including familiar places, characters, animals and even vegetables.